The longbow as we recognise it today, measuring around the height of a man, made its first major appearance towards the end of the Middle Ages. Although generally attributed to the Welsh, longbows have in fact been around at least since Neolithic times: one made of yew and wrapped in leather was found in Somerset in 1961. It is thought that even earlier finds have been uncovered in Scandinavia.

The Welsh however, do appear to have been the first to develop the tactical use of the longbow into the deadliest weapon of its day. During the Anglo-Norman invasion of Wales, it is said that the ‘Welsh bowmen took a heavy toll on the invaders’. With the conquest of Wales complete, Welsh conscripts were incorporated into the English army for Edward’s campaigns further north into Scotland.

Although King Edward I, ‘The Hammer of the Celts’, is normally regarded as the man responsible for adding the might of the longbow to the English armoury of the day, the actual evidence for this is vague, although he did ban all sports but archery on Sundays, to make sure Englishmen practised with the longbow. It is however during Edward III‘s reign when more documented evidence confirms the important role that the longbow has played in both English and Welsh history.

Edward III’s reign was of course dominated by the Hundred Years War which actually lasted from 1337-1453. It was perhaps due this continual state of war that so many historical records survive which raise the longbow to legendary status; first at Crécy and Poitiers, and then at Agincourt.

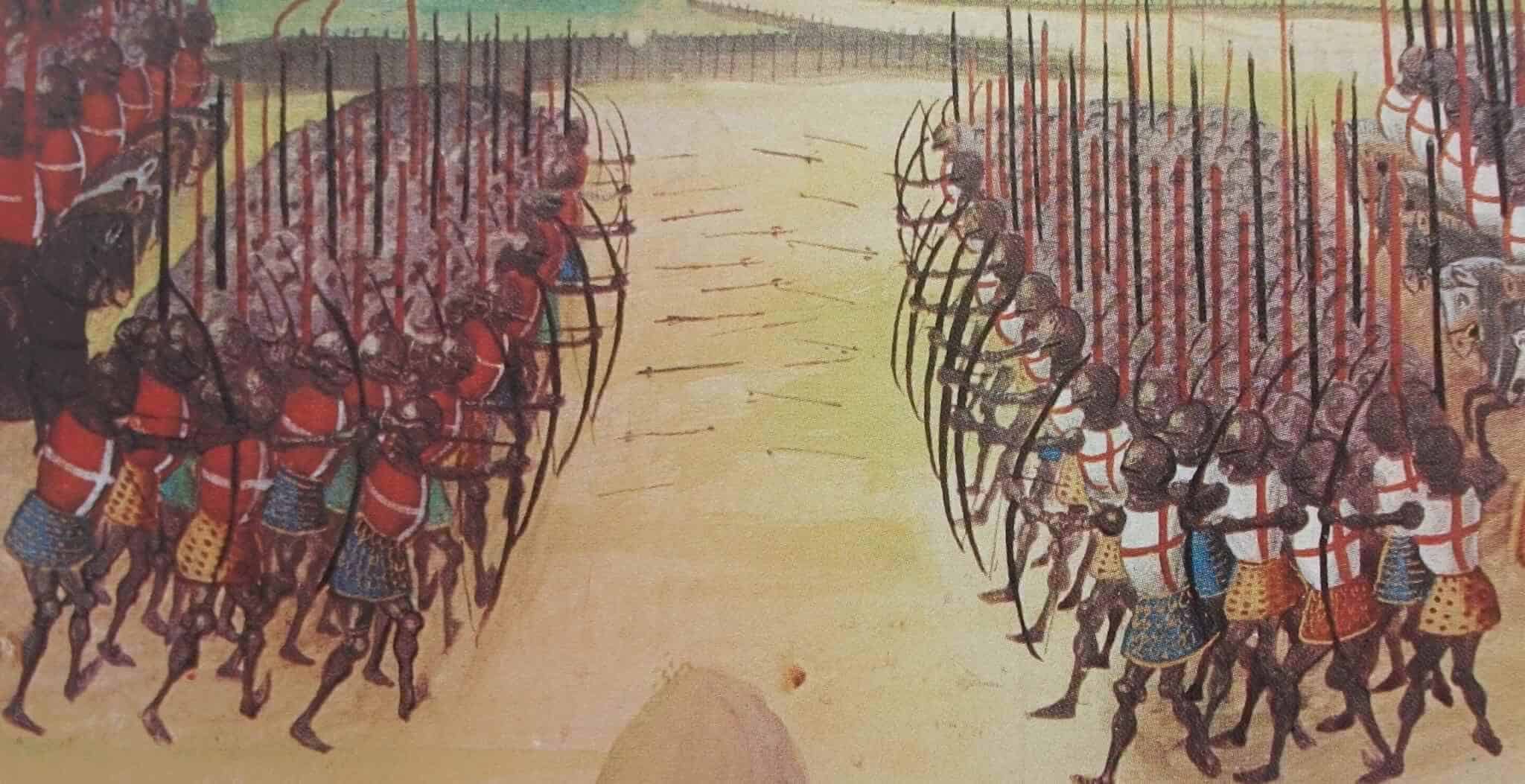

Battle of Crécy

After landing with some 12,000 men, including 7,000 archers and taking Caen in Normandy, Edward III moved northwards. Edward’s forces were continually tracked by a much larger French army, until they finally arrived at Crécy in 1346 with a force of 8,000.

The English took a defensive position in three divisions on ground that sloped downwards, with the archers on the flanks. One of these divisions was commanded by Edward’s sixteen year old son Edward the Black Prince. The French first sent out the mercenary Genoese crossbowmen, numbering between 6000 and 12,000 men. With a shooting rate of three – five volleys per minute they were however no match for the English and Welsh longbow men who could release ten – twelve arrows in the same amount of time. It is also reported that rain had adversely affected the bowstrings of the crossbows.

Philip VI, after commenting on the uselessness of his archers, sent forward his cavalry who charged through and over his own crossbowmen. The English and Welsh archers and men-at-arms held them off not just once, but 16 times in total. During one of these attacks Edward’s son The Black Prince came under direct attack, but his father refused to send help, claiming he needed to ‘win his spurs’.

After nightfall Philip VI, himself wounded, ordered the retreat. According to one estimate French casualties included eleven princes, 1,200 knights and 12,000 soldiers killed. Edward III is said have lost a few hundred men.

Battle of Poitiers

Details concerning the Battle of Poitiers in 1356 are in fact quite vague, however it appears that some 10,000 English and Welsh troops, this time led by Edward, Prince of Wales, also known as the Black Prince, were retreating after a long campaign in France with a French army of somewhere between 20,000 – 60,000 men in close pursuit. The two armies were separated by a large hedge when the French found a gap and attempted to break through. Realising battle was about to commence The Black Prince ordered his men to form their usual battle positions with his archers on the flanks.

The French, who had developed a small cavalry unit specifically to attack the English and Welsh archers, were not only brought to an abrupt stop by the number of arrows that showered down upon them, they were by all accounts routed. The next attack came from the Germans who had allied themselves with the French and were leading the second cavalry attack. This was also stopped and it is said that so intense was the attack by the English and Welsh archers that at one point some ran out of arrows and had to run forward and collect arrows embedded in people lying on the ground.

Following a final volley of his archers’ release, the Black Prince ordered the advance. The French broke and were pursued to Poitiers where the French King was captured. He was transported to London and held to ransom in the Tower of London for 3,000,000 gold crowns.

Battle of Agincourt

A 28-year-old King Henry V set sail from Southampton on 11th August 1415 with a fleet of around 300 ships to claim his birthright of the Duchy of Normandy and so revive English fortunes in France. Landing at Harfleur in northern France, they besieged the town.

The siege lasted five weeks, much longer than expected, and Henry lost around 2,000 of his men to dysentery. Henry took the decision to leave a garrison at Harfleur and take the remainder of his army back home via the French port of Calais almost 100 miles away to the north. Just two minor problems lay in their way – a very, very large and angry French army and the River Somme. Outnumbered, sick and short of supplies Henry’s army struggled but eventually managed to cross the Somme.

It was on the road north, near the village of Agincourt, that the French were finally able to stop Henry’s march. Some 25,000 Frenchmen faced Henry’s 6,000. As if things couldn’t get worse it started to pour with rain.

On 25th October, St Crispin’s day, the two sides prepared for battle. The French though weren’t to be rushed and at 8.00am, laughing and joking, they ate breakfast. The English, cold and wet from the driving rain, ate whatever they had left in their depleted rations.

Following an initial stalemate, Henry decided he had nothing to lose and forced the French into battle and advanced. The English and Welsh archers moved to within 300 metres of the enemy and began to release their arrows. This sparked the French into action and the first wave of French cavalry charged, the rain-soaked ground severely hindering their progress. The storm of arrows raining down upon them caused the French to become unnerved and they retreated into the way of the now advancing main army. With forces moving in every direction, the French were soon in total disarray. The field quickly turned into a quagmire, churned up by the feet of thousands of heavily-armoured men and horses. The English and Welsh archers, some ten ranks deep, rained tens of thousands of arrows down onto the mud trapped French and what followed was a bloodbath. The battle itself lasted just half an hour and between 6,000 and 10,000 French were killed whilst the English suffered losses in the hundreds.

After three hundred years the dominance of the longbow in weaponry was coming to an end and giving way to the age of muskets and guns. The last battle involving the longbow took place in 1644 at Tippermuir in Perthshire, Scotland during the English Civil War.

Timeline of the Longbow

| 50,000 BC | Arrowheads found in Tunisia, Algeria and Morocco |

| Circa 3,000 BC | Longbow first appears in Europe |

| Circa 2,690 BC | Evidence of longbow being used in Somerset, England |

| 950 | Historical evidence of crossbows in France |

| 1066 | Battle of Hastings (Harold shot in eye?) |

| 1100’s | Henry I introduces law to absolve any archer if he kills another whilst practising |

| Circa 1300 | Edward I bans all sports other than archery on Sundays |

| 1340 | Start of The One Hundred Years War |

| 1346 | Crécy |

| 1356 | Poitiers |

| 1363 | All Englishmen ordered to practice archery on Sunday and holidays |

| 1377 | First mention of Robyn Hode in the poem Piers Plowman written by William Langland |

| 1415 | Agincourt |

| 1453 | English archers killed by cannon and lances attacking French artillery position at Castillon, the last battle of The One Hundred Years War |

| 1472 | English ships ordered to import wood needed to make bows |

| 1508 | To increase use of longbows, crossbows are banned in England |

| 1644 | Tippermuir – Last battle involving the longbow |

| 17th century | Muskets become more popular |

Published: 4th March 2016