The one craftsman guaranteed to have a crowd around him at a medieval fayre is the arrowsmith; sparks flying as he expertly forms a lump of metal into an efficient and deadly head for yet another arrow.

As he rests, what can he tell his audience of the history of arrowheads?

Long before mankind had learnt to use metals, early hunter gatherers used carefully chipped – or knapped – pieces of flint to ensure that the business end of their arrows produced maximum haemorrhage. Two basic styles of these are known: the leaf shape and the familiar triangular shape with barbs. Archaeological finds indicate that the earliest use of projectiles with such points is somewhere around 6,000 years ago; although no one can say for certain that these were shot from bows and may have been thrown, using a throwing stick.

By the Bronze Age, it became possible to tip arrows with heads made from this wonderful metal, and these were made by casting.

The early use of archery would almost certainly have been for hunting, an easier and less dangerous way of providing something for the pot than driving an animal over a cliff or spearing it. However, it would not have been long before someone realised that they could also dispatch another human being, such as an enemy or a competitor.

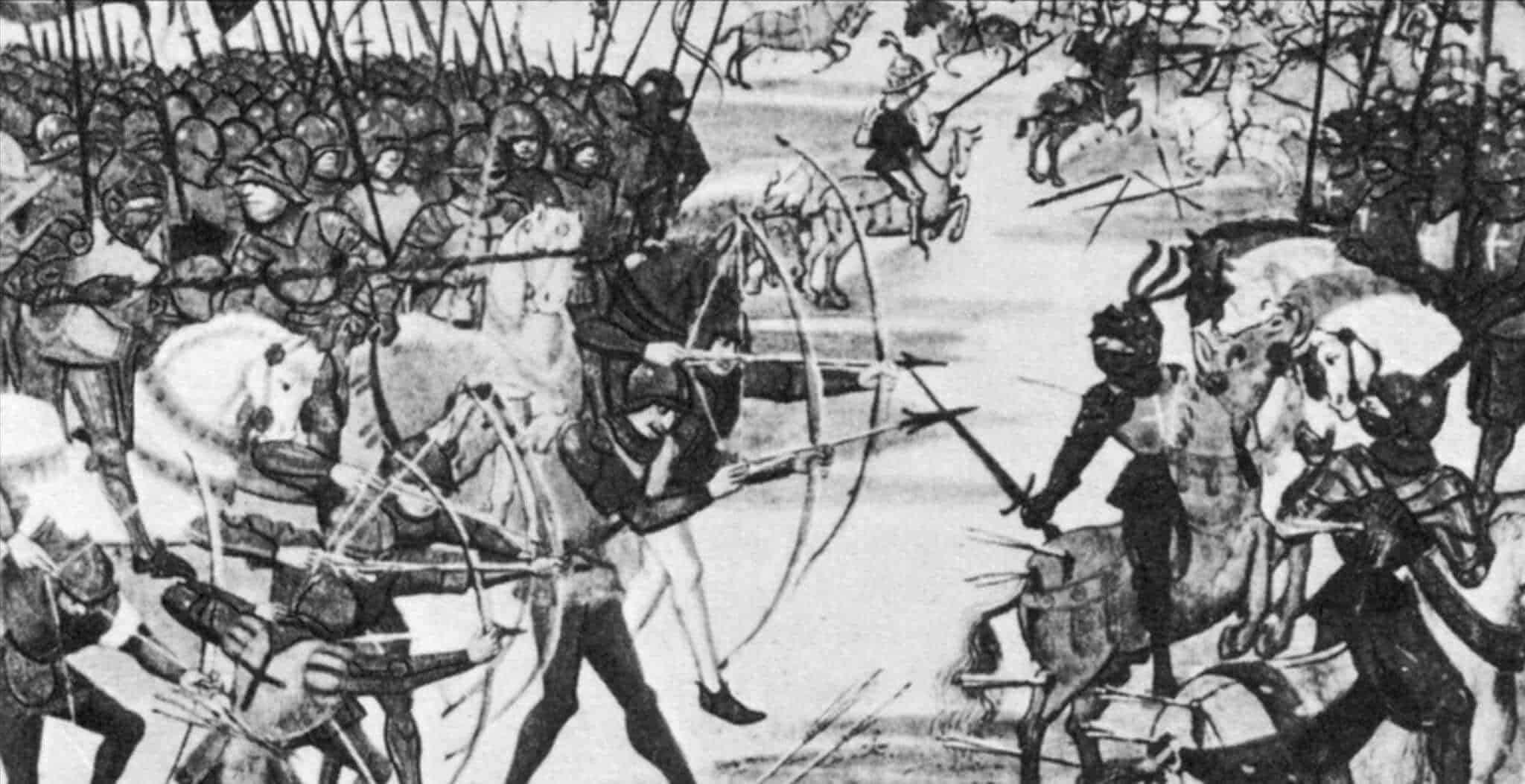

Once people began to settle and regard a particular piece of land as theirs, the way was open for conflict with others. Archery thus became a significant part of many armies and the arrowsmiths sought to make the most effective heads for killing. As armour improved, so arrow heads were adapted and their shape changed, requiring better armour; and so smiths made more efficient heads and so the race went on.

So by the Middle Ages and right up until the bow ceased to be a weapon of war, there have been numerous shapes for different applications. Two accepted typologies are in use to identify general shapes, one by the London Museum the other by Jessop. With some of the heads it is not always entirely clear what their specific function was, although educated guesswork and physical testing can usually come up with a reasonable supposition.

Even while hunting and warfare were the main uses for archery, many folk liked to shoot for simple pleasure – and a bit of competition – using a variety of targets or butts. This activity did not require a killing head, so simpler metal points developed. Modern versions of these are still in use today by modern archers.

Contrary to what Hollywood suggests, someone hit by an arrow does not necessarily drop dead. Although the penetration potential is very high, other factors are also in play. Many arrow heads included barbs of various kinds which prevented them being withdrawn and methods of removal were nasty, to say the least. Many died of blood poisoning rather than the wound itself. Indeed, Richard the Lionheart died from an infected shoulder wound, inflicted by a crossbow bolt, during the siege of the castle of Chalus-Chabrol in 1199.

Extensive testing has shown that the force with which an arrow hits its target is considerable, as is its penetrative power; I understand that a bullet proof or “stab” vest offers little protection from an arrow. I have also seen a man in full armour taken off his feet by an arrow with a blunt “safety” head.

Young agile re-enactors might leap into the saddle in full armour, but we know that in the past men were suffocated in the mud when they fell and could not rise. Modern tests have also shown that the impact of an arrow from a powerful warbow is such that it is enough to kill by blunt trauma alone.

But what of the various types and their uses? These cover a number of variations on the well known triangular shape with backward facing barbs, which come in a range of sizes right up to the massive one known as a horse head. Galling the horses, disrupting an advance, was part of the tactics of warfare.

Other heads were more like square shaped cold chisels designed to punch their way into armour, or leaf shaped heads with close lying barbs. There was the bodkin, a long thin head best suited for attacking mail. with a shorter version for plate armour; and one which looked like a small elongated basket, to hold flaming material to form a fire arrow.

Hunters of the past would have used broadheads similar to those used today in places where bow hunting is allowed. Two however were quite different: the blunt and the crescent or forker. It is well known that the former was used for small game and birds, since it kills by impact without causing unnecessary damage to the hunter’s next meal. This type of head was the only one which peasants were allowed to use within the forests set aside for the Lord or King to hunt, since a blunt could not injure the King’s deer.

The forker however, puzzles archer historians. Did it cut ropes or rigging, or slit sails? Tests have shown that each is possible – but only in carefully controlled conditions of distance and angle. A further recent trial suggested another use, for ‘birding’. It was found that the crescent shape bunched the feathers together allowing a kill without damage.

Heads for recreational archery protected the end of the arrow and ensured it penetrated the target. They were based on a simple theme which, with minor changes, became the bullet shape still used today. Again, there were variants: the blunt head used by those practicing at the butts – which incorporated a central spike, enough to stick in the butt, but not so far as to make removal difficult – whilst seventeenth century archers made sure they drew the arrow to the correct distance by using the “silver spoon” or “ridged” head. The ridge around the head could be felt on the hand as a draw length check.

Today, arrowsmiths still make arrowheads as in the past. Two of them are members of the CGTBF – the Craft Guild of Traditional Bowyers and Fletchers – and so the skill is preserved and perpetuated.

By Veronica-Mae Soar, Society of Archer Antiquaries