When King Charles IV of France passed away in February 1328, a succession crisis emerged, pitting Edward III of England against Philip, Count of Valois and thus steering two nations on course for decades of hostility.

The battle for the throne ended in victory for the House of Valois and thus Philip became King Philip VI of France, leaving Edward to lick his wounds back in England.

The French magnates had made their choice and Edward, who was still a minor at the time, acquiesced and let the decision go unchallenged, but for how long?

By the early 1330’s the dynamic at play was not to Edward’s liking. Still in possession of Gascony, an important commercial partner for England, Edward held the title of Duke of Gascony and found himself subject to the French Crown as a vassal of King Philip VI.

This did not sit well with the English king and by 1337, the situation escalated when Philip VI decided to confiscate Gascony and launched a raid on the southern coast of England in a simple act of provocation which left Edward with the perfect justification for war.

Edward in response declared that the French Crown was in fact his and even went to the trouble of adding the fleur-de-lys to his coat of arms, an indication of his intentions towards the French.

This was the moment that marked the beginning of the Hundred Years’ War.

With Edward III’s renewed interest in the French Crown, both sides sought alliances, with England turning to the Low Countries and France looking for support from Scotland and Spain.

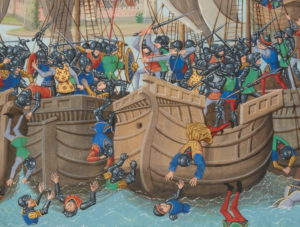

Whilst the stage was set, international conflict did not break out until 24th June 1340 at the Battle of Sluys, sometimes referred to as the Battle of l’Écluse. This encounter would be the first of many between the English and French, marking decades of further skirmishes.

The battle itself took place at Sluys, in the Scheldt estuary of the Low Countries and would prove a first major naval victory for the English who were able to capture and sink the French fleet.

Edward III’s fleet amounted to around 150 ships and was able to outmanoeuvre its opponents and surprise them in this narrow channel, resulting in the majority of the French fleet captured and the death of around 20,000 men.

The next significant encounter came six years later at the famous Battle of Crécy in August 1346 when the French army led by King Philip VI attacked Edward III’s men.

This would prove to be a notable triumph for the English whilst also representing an important step in the evolution of medieval warfare.

The conflict played out in northern France, as the English had landed in Normandy in July and subsequently sacked many towns as they traversed their way through the area.

Just before the battle played out, King Philip’s son, John, Duke of Normandy had already laid siege to Aiguillon in Gascony in April 1346.

Only a year previously, Henry, Earl of Lancaster had travelled to this part of France with around 2000 men. Thus, the town found itself a French target and was forced to defend itself using an Anglo-Gascon army.

Fortunately on this occasion, the siege proved unsuccessful with the Duke of Normandy and his men forced to surrender as they were never able to blockade the town completely, leading in time to their own supply issues. Eventually, by August 1346, with growing pressure on Philip and the prospect of conflict at Crécy, the French, upon the orders of Philip VI, were forced to abandon the siege.

Meanwhile, they turned their attentions back to Crécy. Edward would prepare his army on a hillside near Crécy-en-Ponthieu forcing the French cavalry to attempt to charge uphill in muddy conditions. As such, the battle would prove the effectiveness of the archery of the English infantry against the large-scale French cavalry who suffered a heavy defeat and many casualties.

After numerous French attempts to charge, their efforts proved futile against the English archers, leaving Edward III and his men able to claim success. By the end of the battle the French are thought to have lost around 1,200 knights in addition to thousands of other fighters.

This particular confrontation was significant, not only in the context of the Hundred Years’ War but for future military strategy as the use of the longbow would become prevalent as a standard in medieval warfare.

Meanwhile, the English win would help Edward’s army onto the next step of their campaign: besieging Calais.

Only a week after declaring victory at Crécy, Edward III and his men began their plans to besiege the fortified port of Calais. They began by investing the port, which essentially meant surrounding the town and ensuring that it was impossible to escape.

Whilst the garrison would hold off the English forces for almost a year, eventually lack of supplies began to get the better of them.

Out at sea the French attempted to relieve Calais with a fleet of forty ships, however their efforts were scuppered by the English. The Battle of Crotoy in June 1347 ended in English victory under the Earl of Northampton and Earl of Pembroke whilst also preventing the French from saving Calais.

In desperation the commander of the garrison port, Jean de Vienne, contacted King Philip begging for further help. This assistance came in the form of an army in July of around 20,000 French soldiers.

Sadly for those that were relying on this breakthrough, the overwhelming and well-entrenched English and Flemish forces forced Philip’s men to withdraw.

Not long afterwards, Calais capitulated and the English gained a valuable and strategic territory which they would hold onto long after the end of the Hundred Years’ War.

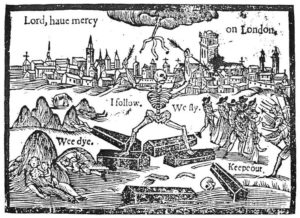

By 1347 the English had an impressive amount of victories under their belt, both on land and at sea. Unfortunately for all involved, something far deadlier and more unpredictable was about to take hold: the Black Death.

The first recordings of the plague came in 1347 with Genoese traders who had introduced the disease into Europe. In no time at all, it swept around Europe, heading from Italy northwards and by the following year was recorded in England as well as large parts of Scandinavia.

With the conflicts of the Hundred Years’ War interrupted, the Black Death worked its way around the continent, leaving in its wake such high rates of mortality that it would have a permanent impact on the demographics, and thus economics, of these European kingdoms.

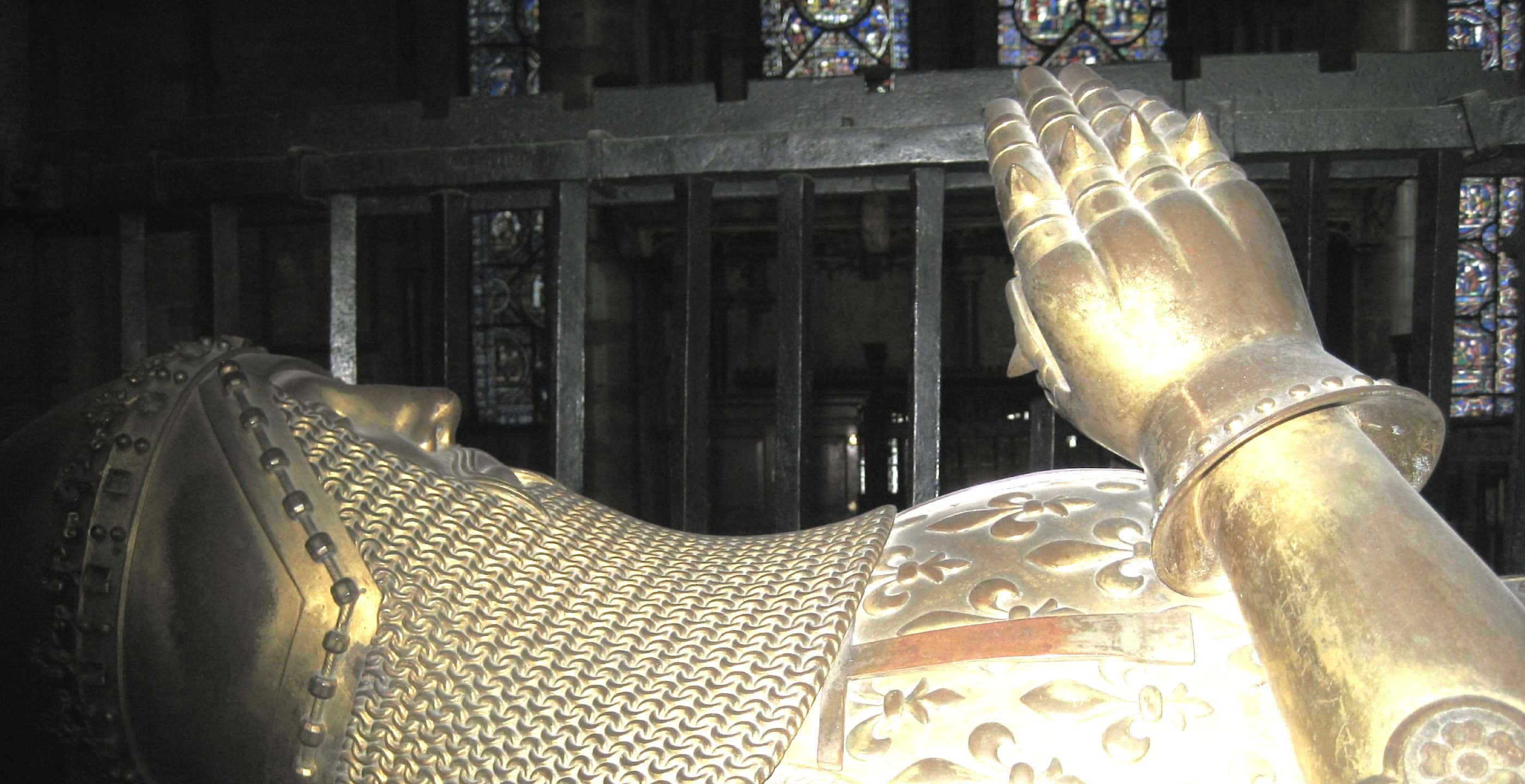

Edward III meanwhile, would use this time to concentrate on other matters of his concern, namely his son, also named Edward, later referred to as the Black Prince, who would eventually follow in his father’s footsteps and take up his mantle against the French.

The Prince, who was based in Gascony, would in time earn great popularity and recognition for his military exploits, displaying himself as an embodiment of a chivalrous fighter.

After the hostilities had been postponed by the emergence of the Black Death, the most significant battle to follow was in Nouaillé, near the city of Poitiers.

In September 1356, Edward the Black Prince led his army into battle, many of whom were veterans of the Battle of Crécy. The army under Prince Edward was comprised of English, Welsh, Gascon and Breton troops who quickly found themselves under attack from the large and imposing French forces allied with Scotland under the watchful eye of the new King of France, King John II.

The English, despite being outnumbered, were able to inflict heavy losses on the French, capture Poitiers for four years as well as capturing King John, his son and a number of significant members of the French nobility.

As a result of their capture, the French were now in full-scale crisis management, leaving Dauphin Charles in charge whilst revolts began to break out across the country.

Meanwhile, the English emerged victorious, with Prince Edward a notable and celebrated general and with much fewer fatalities than the French.

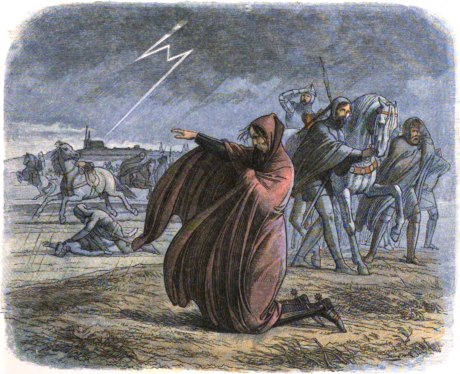

That being said, on 13th April 1360, a freak hailstorm would kill and injure many of Edward’s men as they finalised their plans to besiege the town of Chartres. This freak event would become known as Black Monday and killed around 1000 men leaving Edward and the remainder of his forces in shock and fearing this natural phenomenon as an omen for the future.

After several failed attempts to form some kind of truce, a month after Chartres the Treaty of Brétigny was signed between the two nations with favourable terms for the English.

This treaty would formally recognise Edward’s claim to around three-quarters of France and in turn, Edward withdrew the larger claim for the French Crown.

Meanwhile, the French agreed to pay a ransom for King John, however he would end his days dying in captivity.

The treaty, later ratified as the Treaty of Calais, would conclude this chapter of the Hundred Years’ War better known as the Edwardian phase, named as such because it was initiated by King Edward III when he laid claim to the French Crown.

It had lasted almost three decades from 1337 until 1360, in which time both France and England had incurred losses and succumbed to the virulence of the plague. Nevertheless, this dynastic conflict was far from over and as the French took stock of their setbacks and the English reflected on their naval and land victories, the battle for supremacy looked set to continue….

Who would become the ultimate victor? Only time would tell.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 6th September 2021