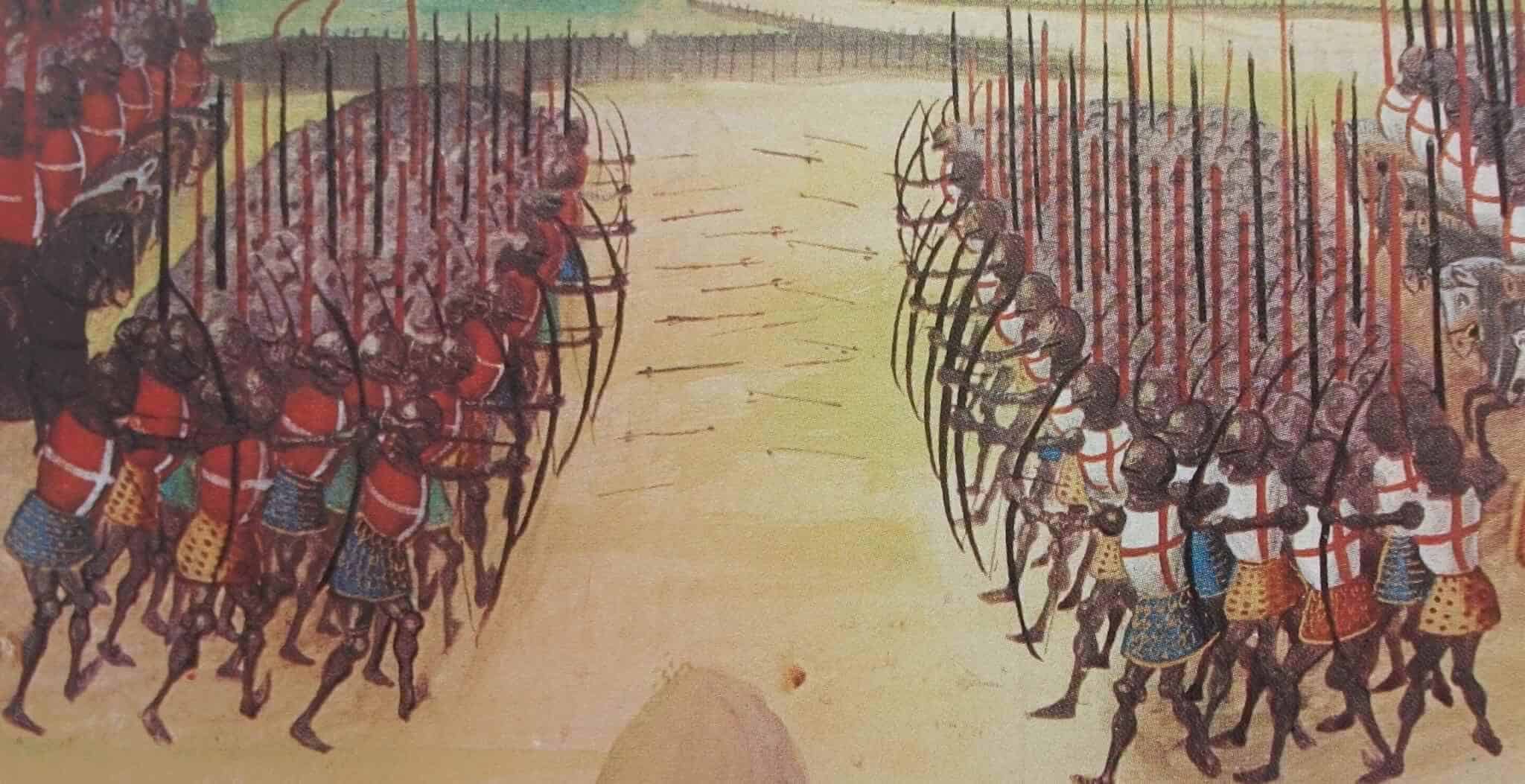

Like most conflicts, the Hundred Years’ War emerged from a variety of issues which on this occasion, culminated in recurrent battles between the French and English Crown, with both parties vying for ultimate supremacy.

In fourteenth century Europe, French and English interests overlapped which would ultimately lead to battles fought for over a century and spanning five generations of kings.

The origin of such tension was rooted in a succession crisis emerging from the fact that the English royal family were French in origin. Such circumstances would lead the English Crown to maintain historical titles and claims to territory on the French mainland, thus leading to titles and territories in dispute.

Moreover, Europe was experiencing great social, political and economic upheaval, made even worse by the ensuing Black Death which ripped its way through Europe leaving a permanent impact on the demographics of the continent.

By the time conflict broke out in May 1337 with the confiscation of the English duchy of Guyenne by the French Philip VI, skirmishes between the English and French had already been in full swing, with the origins of these crises dating back to the time of William the Conqueror who was Duke of Normandy as well as the King of England. His power and possession of the English Crown would lead to centuries of further disputes where interests, land, power and the Crown itself were called into question.

As King William I was the first sovereign ruler of England as well as a part of the esteemed French nobility, he was in possession of fiefs on mainland Europe which would be passed on to subsequent holders of the English Crown.

By the time the Angevin dynasty came into power with King Henry II in 1154, the power of the English Crown straddled both France and England, with Henry holding the titles of Duke of Normandy, Count of Anjou and Duke of Aquitaine.

Henry, himself a descendant of William the Conqueror via his mother, Empress Matilda, was also part of the Angevin dynasty via his father, Geoffrey Plantagenet, Count of Anjou.

With the power of his family being held both in the Angevin kingdom as well as through a rich lineage of Norman nobility, the estates of the family, both in England and France were extensive. Moreover, since the 11th century, the French county of Anjou had found itself gaining greater autonomy from the French king and thus held much authority in its own right through advantageous marriages and political agendas, placing it well and truly at the heart of power.

Inevitably, this did not sit well with the French Crown as the existence of the Angevin empire looked to threaten its authority of France and its central command. As a result conflict ensued, a precursor to the Hundred Years’ War which developed a few generations later.

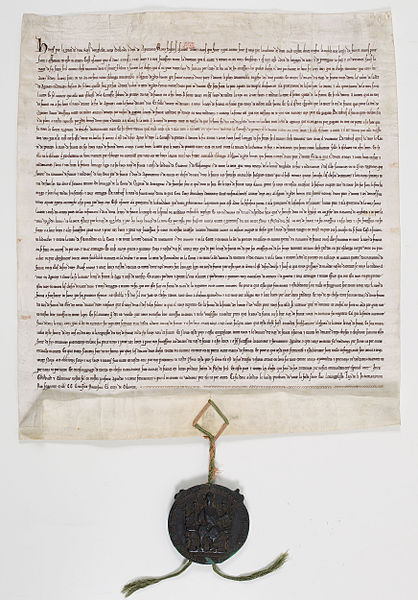

The struggles incurred at this time would be addressed by a treaty arranged and ratified in December 1259 by King Henry III of England and Louis IX of France.

The Treaty of Paris would give Henry III the duchy of Guyenne, however he rescinded his claims to Anjou, Normandy and Poitou, representing the territorial purge of the former King Henry II’s imperial reach.

In return for this loss, Louis IX would offer territory designed to protect the border of Guyenne.

Whilst the treaty posed a tangible route to peace between the two figures, problems would arise in the future leading to further treaties and with each passing king, the potential for conflict grew.

One of the first visible signs that trouble was brewing came in 1293 in a skirmish between ships from England and that of a Norman fleet. The following year events would escalate further when Philip IV of France confiscated Guyenne and demanded reparations.

In time, Philip’s power would envelope the entire duchy, with the support of his brother Charles, the Count of Valois and his cousin, Robert II of Artois. Whilst the power grab in France was well and truly underway, Edward I back in England created an alliance with Guy of Dampierre, Count of Flanders, a potential rebel with whom he could join forces against France.

Despite these political machinations, the intervention of Pope Boniface VIII proved enough to halt any planned hostilities, at least for the time being.

Meanwhile back in England, Edward I saw fit to strengthen the political system as well as bolster the military prowess of his country by conquering Wales as well as gaining control of Scotland.

When his son King Edward II came to power, the English Crown would suffer terribly during his reign as the country incurred military losses as well as suffering from the effects of the Great Famine.

When he was deposed in 1327, his fourth son became heir and was crowned King Edward III. He was keen to restore England to its former glory as an effective military power, an important commercial competitor as well as, perhaps most importantly for Edward himself, a royal authority.

During his reign he was able to accomplish these goals as great advances were made including in legislation for parliament. He was also able to defeat the Kingdom of Scotland which would add another dynamic into the fray, ultimately contributing to a growing alliance between Scotland and France.

Meanwhile in February 1328, Charles IV of France died, leaving behind no male heir to succeed him. This thrust the French Crown into a succession crisis as the House of Capet lineage became void and the decision as to who should fulfil the role was left up to a group of magnates.

As such there were two main claimants to the throne, on the one side Philip, Count of Valois who was son of Philip IV’s brother Charles and on the other side Edward III of England who staked his claim to the title through his mother Isabella, the sister of Charles IV.

With the House of Valois versus the House of Plantagenet, the real battle was that between the power of the French Crown versus the English Crown, thus bringing together centuries of hostility and animosity. This succession crisis was the final straw in building tensions and the ultimate factor preceding the fighting of the Hundred Years’ War.

When the group of magnates made their decision as to whom would inherit, the possibility of conflict seemed inevitable as the Count of Valois was chosen leaving Edward III enraged.

Whilst Edward was not keen to take this decision lying down, the newly appointed King Philip VI soon proved himself to be a formidable opponent when he won the Battle of Cassel in August 1328, suppressing Flemish rebels.

By 1334, war seemed imminent as Edward regretted acquiescing to Philip’s demands, particularly when Philip of France offered support to David II of Scotland against England.

Edward was also keen to recover his French losses as well as to curtail the worrying alliance formed between Scotland and France against their common enemy of England.

Both sides were no longer in any doubt that war was looming and as such the preparations for battle would commence. Whilst Edward looked for support in the Low Countries, Philip was able to form an alliance with Castile.

In May 1337, Philip formally declared Guyenne was confiscated: five months later Edward declared that the French Crown was his and even added the fleur-de-lys to his coat of arms.

Thus generations of competition finally came to a head and the Anglo-French conflict became part of a larger chain of events called the Hundred Years’ War.

It would take another century before the conflict reached its conclusion with a French victory, leaving England forced to satisfy itself as an island nation having lost all but Calais.

The rivalry between these two ambitious kingdoms would linger for many centuries to come.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 31st August 2021