King of England from January 1327, Edward III was famous for his victories in the Hundred Years War, but would also face many challenges after inheriting a chaotic and disorderly mantle from his recently deposed father, Edward II.

His father had not only suffered a humiliating defeat by the Scots at Bannockburn but his close personal relationships with “favourites” such as Piers Gaveston made him a source of much scrutiny.

In the end his personal relationships would prove the death of him, with his wife, Isabella of France arranging with her lover, Roger Mortimer, to have him deposed. His imprisonment and death at Berkley Castle marked the beginning of Edward III’s ascension to power.

With his mother Isabella having arranged for the deposition of his father, Edward was proclaimed king and on 1st February 1327, at the tender age of fourteen, was crowned at Westminster Abbey.

Unfortunately for young Edward, his ascendancy to throne merely provided Mortimer with more power in court, as the de facto ruler of the kingdom.

Isabella’s lover Roger Mortimer was now abusing his power in order to increase his lands and titles, leading to a surge in his unpopularity. At this time, Edward was a nonentity in a much bigger game of power politics; having rid himself of Edward II, Mortimer was now the one calling the shots.

Mortimer’s greediness continued as did the downward spiral of his popularity, particularly after the Battle of Stanhope Park in County Durham in which the Scots achieved a major victory. The demoralising defeat led in 1328 to the agreement known as the Treaty of Northampton, essentially guaranteeing Scottish independence.

Whilst Edward had no choice but to agree, he would bide his time and at a later date revoke his support for the arrangement.

Meanwhile, the young king became increasingly frustrated with his guardian who showed him a distinct lack of regard. The hostility would continue to grow when Edward married Philippa of Hainault in January 1328 at York Minster. The marriage and the subsequent child that followed, Edward of Woodstock in 1330, signified more challenges to Mortimer’s power.

Eventually, sensing the time had come, Edward took clear and decisive action against Mortimer.

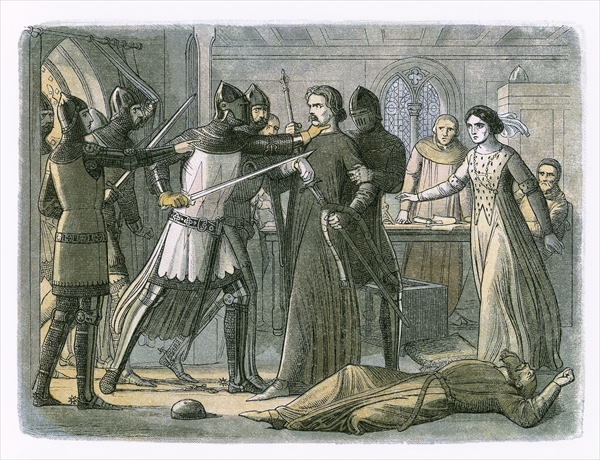

In the same year as his first son’s birth and with the help of close aide William Montagu, Edward launched a surprise attack on Mortimer at Nottingham Castle in October 1330. Mortimer was subsequently tried for treason and executed, leaving aside the more delicate matter of his mother’s fate.

Isabella found herself treated with more leniency, spending the rest of her life in Norfolk, having lost the prestige to which she had become accustomed. Mortimer’s death thus marked the beginning of Edward’s real ascension to power.

Edward faced two main tests during his reign: firstly, his approach to the prospect of war, namely with Scotland and France and secondly, Edward’s approach to reconciling relationships with those leading and titled figures whom his father had so greatly alienated.

In 1329, the death of Robert the Bruce and the accession of David II who was only 5 years old at the time, allowed Edward an ideal opportunity to renege on the Treaty of Northampton.

By 1332, Edward enacted his ambitions in Scotland by supporting the installation of Edward Balliol as King of Scotland, usurping David II. Balliol had the support of a group of English magnates, known as the” Disinherited”, a name which alluded to their loss of land.

The group managed to secure a victory at the Battle of Dupplin Moor where they sought to place Edward Balliol as the king. However, this was a move which initiated serious opposition, leading to Balliol’s expulsion and the need for Edward III to step in as King of England.

Edward’s involvement was motivated by a desire to re-install the over-lordship of Scotland, previously established by Edward I. Thus, in support of Balliol, Edward instigated important military campaigns at Berwick, launching a devastating blow to enemy forces at the Battle of Haildon Hill.

At this moment, Edward was able to oversee Balliol’s tightening grip of Scotland which saw him force the young David II who was now nine years of age to flee for his life to France. Meanwhile, Balliol gained the lands of southern Scotland. Balliol however was never able to execute real and sustained power over Scotland and in very little time his weak control was ceded and by 1338 Edward was forced to recognise and conclude a truce with the Scots.

The dynastic challenges of Scotland proved in the long run to occupy Edward’s attention, however for now he turned his head towards France.

The conflict brewing between England and France was born out of a much longer and simmering tension, arguably from as far back as the Norman Conquest. In the reign of Edward III, the conflict gained more prominence in light of the ascendancy challenges which emerged from the death of Charles IV of France who passed away without any children.

Edward III of England was Charles IV’s nephew and therefore had a legitimate claim to the throne, however it was subsequently rejected by the French parliament who instead chose Philippe VI, Charles’s cousin as the new face of France.

To add more fuel to the fire, continued French resistance to the presence of the Plantagenets in Gascony was growing.

When sparks really began to fly however was when in 1334, Philippe chose to offer support to David II of Scotland and two years later began making military preparations for an invasion of England.

Edward was not one to back down and over the coming year made clear his intentions for claiming the French throne. In due course, a series of Anglo-French hostilities erupted and formed part of a much larger chain of events known later as the Hundred Years War.

With Philippe staking his claim to Gascony, skirmishes broke out; an invasion by the French did not produce a clear outcome and by March 1340 Edward had declared himself King of France, even choosing to add the fleur-de-lys to his coat of arms.

It was at this time that he dealt with the other pressing concern of his reign, healing the divisions caused by his father and uniting the barons in his favour.

Such a task was accomplished in the midst of war with France as Edward could not afford to alienate his men back home. By referring to a parliament which acted as a genuine consultative institution, giving powers to revoke or agree, the barons were swept up by shared interests.

Edward needed money to fund his continued military escapades abroad and therefore an increase in taxation was necessary – only with the permission of the parliament of course.

Moreover, he also founded the Most Notable Order of the Garter which brought together his court in a union inspired by Arthurian chivalric attitudes. From its inception, the group consisted of twenty six members including Edward III and his son who met at the chapel in Windsor Castle, cementing their chivalric dedications.

Back on the battlefield, in June 1340 fighting at Sluys resulted in a huge number of deaths, with almost 20,000 French soldiers and sailors losing their life.

Such animosity only led to fleeting truces, with one being made in 1343 and subsequently broken by Edward when he launched a successful invasion of France in 1346. Such actions allowed Edward to spread his tentacles into France, enacting a glorious defeat against his enemies at Crécy where intense hand-to-hand combat allowed the English to overwhelm the French, move on and lay siege to Calais, which they continued to hold for a further two centuries.

In the meantime, back in Scotland, David II had returned, only to be captured by an army led by the Archbishop of York, Walter de la Zouche.

With David II imprisoned, fighting looked set to continue however a much more unpredictable and fierce threat to life was emerging: the outbreak of the Black Death.

The plague first made its appearance in France around 1348 and in very little time decimated a significant proportion of Europe’s fighting population. Understandably, a truce was enacted with fighting unable to continue in light of the pandemic. Now the threat to life came in the form of illness with England and France experiencing significant losses of life.

The social impact as well as political could not be underestimated. With a reduced working population, those that survived were now inclined to demand higher wages, an event which Edward sought to suppress with the introduction of the Statute of Labour in 1351.

Edward however was not exempt from the horrific impact of the Black Death as he experienced a personal loss from the plague, that of his daughter, Joan who died. A reminder for the king, “that we are human too”.

Whilst the plague ravaged Europe and would continue to impact the population in the coming decades, within six years war was resumed with both Scotland and France.

By 1355, Edward’s son known as the Black Prince was rampaging his way through France and in the following year, would experience great victory at Poitiers after capturing the new king of France, Jean II.

This meant that at one stage two kings, Jean II and David II were under the enforced imprisonment of Edward III. Quite a military victory however could not be sustained by Edward, who had to deal with the increasing financial burden of such warfare.

The fortunes of Edward III would continue to fluctuate with a new agreement emerging in 1360, forcing him to withdraw his claim to the throne whilst securing his sovereignty of Gascony.

Whilst his military fortunes were dwindling, domestic issues resurfaced when the court found itself divided. The so-called Good Parliament of 1376 attempted to deal with the problems by removing Edward’s power-wielding mistress, Alice Perrers, although the real power was being seized by John Gaunt.

Meanwhile, Edward III continued to distance himself from the daily strife of court. For the remainder of his life, England was locked in a battle with France. By the time of his own demise in 1377, all that was left for Edward was Calais and a small part of Gascony. The heyday of the Plantagenets was over.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 23rd November 2020