Edward I, known by many names including, ‘Edward Longshanks’, ‘Hammer of the Scots’ and ‘English Justinian’, reigned as King of England from 1272 until 1307.

Edward I was born in June 1239 at the Palace of Westminster, son of King Henry III and Eleanor of Provence. His father decided to give him a name which had not been popular amongst the English aristocracy, in honour of Edward the Confessor. During young Edward’s childhood, poor health was a massive concern, nevertheless as an adult he reached a rather imposing six foot two inches in height, which was extremely rare for the time and earned him the nickname “Longshanks”, meaning “long legs”.

When Edward was fourteen years of age, his father made the decision, for political reasons, to arrange a marriage between his son and thirteen year old Eleanor, the half-sister of King Alfonso X of Castile. The motivation behind this arrangement was induced by fears of a Castilian invasion of Gascony, in southwest France, which at the time was an English province. Therefore, on 1st November 1254 in Castile, Edward married Eleanor, a marriage that would end up producing sixteen children, with only five daughters reaching adulthood and one son, Edward II, outliving his father.

Whilst Edward was young he fell under the influence of his Poitevin uncles, a relationship which was resented by other members of the English aristocracy. Once the uncles were subsequently expelled, Edward became involved with Simon de Montfort, a ringleader of a group of barons in opposition to the misgovernment of Henry III, Edward’s father.

The complexity of relationships worsened when the ‘Provisions of Oxford’ were drawn up in May 1258, introducing a new type of government in which a fifteen member Privy Council would advise the king, three times a year. Edward responded by opposing these reforms but later he began to change his opinion, and the following year he entered into a formal alliance with one of the main reformers. By 15th October, Edward had pledged his support for the barons and their leader, Simon de Montfort. This decision put him at odds with his father who feared he was instigating a coup. It was only a year later that he and his father could be reconciled on the issue.

In 1264, the Second Barons’ War saw Edward side once more with his father Henry and those defending the royal rights; he subsequently reunited with the men he had previously alienated in order to retake Windsor Castle and dispel the rebels once and for all. All attempts at negotiation, instigated by King Louis IX of France failed and the conflict continued. Edward launched a military campaign culminating in the Battle of Evesham in August 1265. The result was Montfort’s death and a final end to the baronial group who were brought down at Kenilworth Castle.

Six years later, Edward would find himself embroiled in further conflict, this time international: the Ninth Crusade, the last major Crusade to the Holy Land. Edward, realising that King Louis IX of France had failed to capture Tunis, decided to set sail for Acre. However his time in this conflict was short-lived, as news from home forced a gradual return home for Edward. Whilst in Sicily he received news of his father’s death but rather than hurrying home, the country was governed by a royal council and Edward was proclaimed king in his absence. Over a year later, he returned to England and was crowned as King Edward I on 19th August 1274.

Edward I became well-known during his reign for his contributions to reforms and developments in administration. He encompassed medieval kingship in all its forms, serving as an administrator, soldier and a man of religious conviction.

In 1274 Edward I began his reforming programme by launching an investigation into government and administrative practices. The findings from this inquiry were recorded in ‘Hundred Rolls’ (a hundred being a subdivision of the shire) and demonstrated where royal rights had been abused by local citizens holding substantial power. Edward wanted to restore law and order, later earning him the nickname of the ‘English Justinian’, after the Byzantine Emperor who codified Roman laws.

During his reign, many statutes were passed in order to deal with the problems that had been identified by the inquiry. One of the main ones included ‘The First Statute of Westminster’ in 1275 which codified many existing laws from the time of the Magna Carta.

Other statutes involved strengthening the policing system of watchmen, restoring public order, caring for traders and merchants and gaining control of the acquisition of land for ecclesiastical purposes. This process was largely influenced by Edward’s chancellor, Robert Burnell, who helped to instigate a complete reorganisation of administration and in doing so, defined a new era in English government.

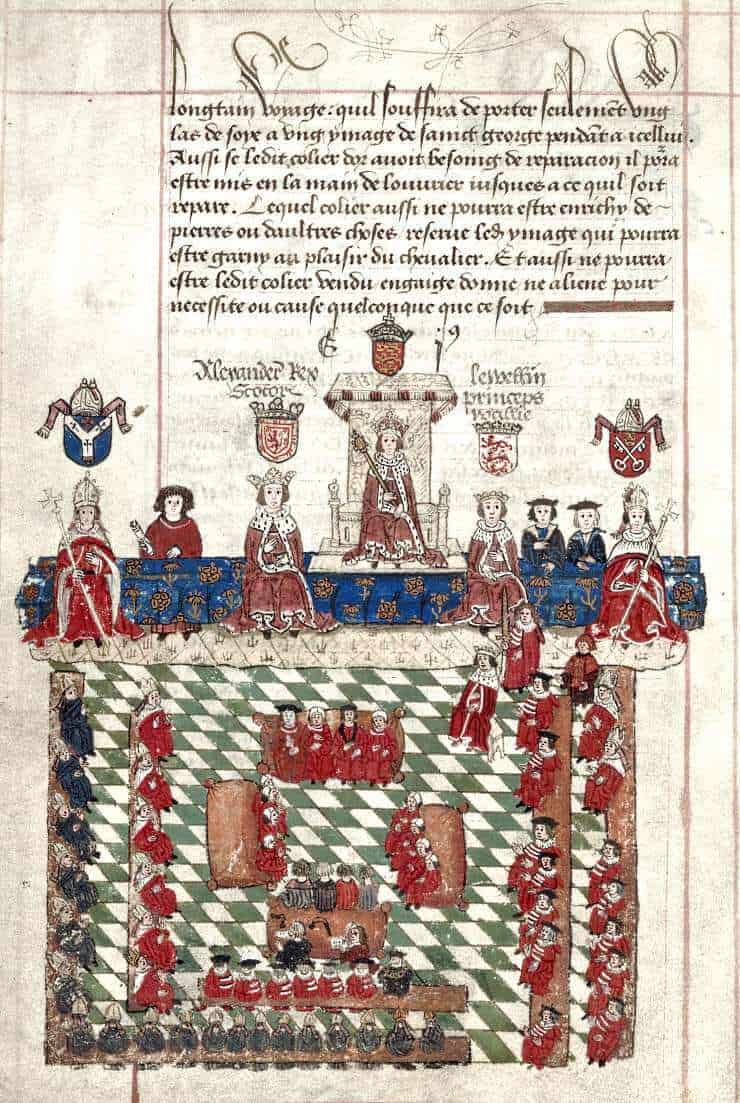

One of Edward I’s greatest legacies is the birth of the English Parliament; under his leadership the meetings became increasingly frequent, amounting to around forty-six occasions during his thirty-five year reign.

In 1275 Edward I called his first Parliament which included members of the nobility, men of the church and also, through writs (orders), the election of two county representatives and two from the towns or cities to also attend. It would not be for some time later that this form of representative parliament became standard practice, known as the Model Parliament, and would eventually form the basis for the conduct of all future Parliaments.

Much of his motivation for developing a form of government in the way that he did was based on raising the necessary funds, through taxation, in order to wage wars. Some of these included waring with neighbours across the Channel. France also happened to be a strong ally of Scotland, another thorn in Edward’s side.

The first part of his reign was dominated by his dealings with Wales. In response to small uprisings occurring in Wales, he decided to take the approach on launching a complete campaign of conquest. He invaded in 1277, defeated Llwelyn ap Gryffyd, the Welsh leader and subsequently went about building castles in order to secure and demonstrate his power in the region. Any signs of uprising were met with further violence, eventually ending Welsh hopes for independence. The country came under complete English framework and authority and by 1301, Edward’s son was named Prince of Wales, a tradition that persists to this day.

Investiture of the first Prince of Wales

Investiture of the first Prince of Wales

His approach to similar issues of self-governance in Scotland however were not so easy to resolve. Edward I responded to uprisings across the border by imposing suzerainty over the country, which was met with a hostile response, continuing to cause conflict beyond his reign.

In 1290 Edward was recognised as overlord of Scotland and at this time made the decision as to who would succeed to the Scottish throne. He chose John Balliol whom he treated as a puppet ruler. The Scottish nobility responded by deposing Balliol and forming an alliance with France. By 1296, Edward had invaded Scotland, imprisoned Balliol in the Tower of London and put the Scottish people under English rule. In this period he earned his nickname, ‘Hammer of the Scots’.

Edward I’s war-waging inclinations necessitated funding and in 1290 he found a way to raise revenue. In this year the Edict of Expulsion was issued, a formal expulsion of all Jews from England, a decision which would generate much needed revenue by appropriating Jewish property. Edward was following the trend of monarchs at the time, instigated by Philip II of France who expelled Jews in 1182. Through this process he hoped to increase much needed funds. The Edict in fact remained throughout the Middle Ages until 1657 when it was reversed by Oliver Cromwell.

Edward I continued to reign until 7th July 1307, when on his way to engage in conflict with Robert the Bruce in Scotland, he died. He was to be remembered as a bombastic, influential and an imposing figure who made decisions, both good and bad, which shaped the country for years to come.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.