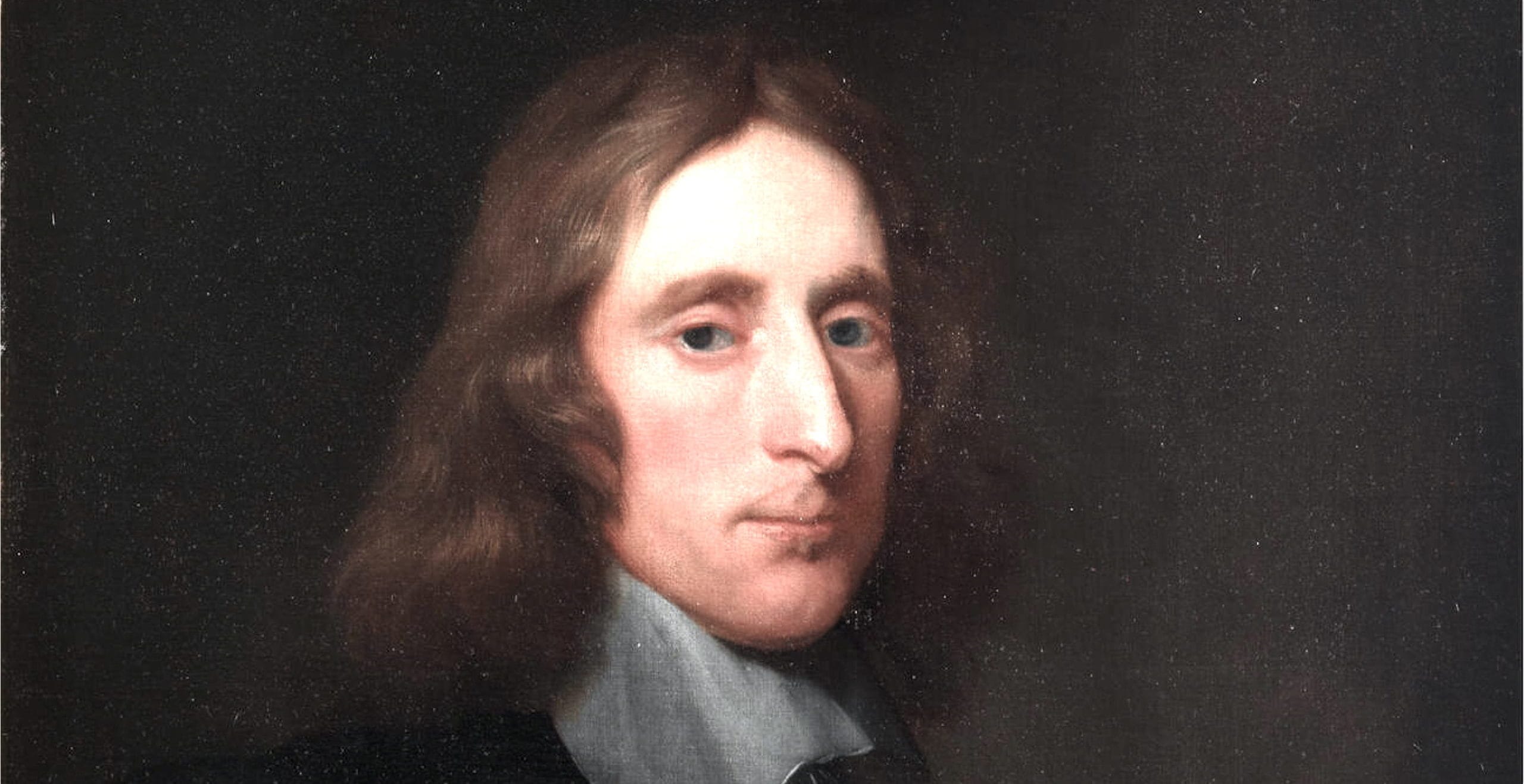

Oliver Cromwell (1599 – 1658), Lord Protector of England

Oliver Cromwell, Lord Protector of England, was executed on 30th January 1661 – two and half years AFTER his death…

Early life

Oliver Cromwell was born in Huntingdon, a small town near Cambridge, on 25 April 1599 to Robert Cromwell and his wife Elizabeth, daughter of William Steward.

Although not a direct descendent of Henry VIII’s chief minister Thomas Cromwell (who was famously promoted to the earldom of Essex but later executed in 1540 when he fell from the King’s favour), Oliver Cromwell’s great-great-grandfather, Morgan Williams, married Thomas’ sister Katherine in 1497.

It was Morgan and Katherine’s three sons who took the surname Cromwell in honour of their famous maternal uncle. This practice was repeated by many of their descendants, who also occasionally used the surname Williams-alias-Cromwell. (In contrast, in the wake of the Restoration some members of the family reverted to the surname Williams temporarily to distance themselves from any links to Oliver Cromwell. )

Morgan Williams and Katherine Cromwell’s eldest son Richard had two sons, Henry and Francis, both of whom also used the surname Cromwell. Like his father before him, Henry went on to be knighted and of his eleven children by his first wife, Oliver’s father Robert was one of the youngest.

Whilst Cromwell’s later life as a military and political leader is well documented, his modest upbringing and early family life is not. Indeed for the first forty years of his life Cromwell remained relatively obscure and he himself remarked in 1654 that he was “by birth a gentleman, living neither in considerable height, nor yet in obscurity”. It was not until the English civil wars of the 1640s that he had the opportunity to rise to power.

Having been educated at Huntingdon grammar school (which now houses the Cromwell Museum) and later at the puritan influenced Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, run by a well-known Calvinist Samuel Ward, Cromwell first made a living as a minor landowner, farming and collecting tenancy rents following the modest inheritance left by his father.

Having been educated at Huntingdon grammar school (which now houses the Cromwell Museum) and later at the puritan influenced Sidney Sussex College, Cambridge, run by a well-known Calvinist Samuel Ward, Cromwell first made a living as a minor landowner, farming and collecting tenancy rents following the modest inheritance left by his father.

Robert passed away in June 1617, which led to Cromwell leaving Cambridge without completing his degree to return to the homestead to support his mother and seven unmarried sisters. Whilst overseeing his father’s land Cromwell is said to have studied law briefly at Lincoln’s Inn of Court in London, where it is thought that he met his wife Elizabeth, daughter of Sir James Bourchier, a knighted London merchant and owner of a significant amount of land with strong connections to the puritan gentry of Essex.

On his small income Cromwell supported both his wife and his ever expanding family (Oliver and Elizabeth had nine children in all, although only six survived into adulthood). As the only surviving son himself, Cromwell was also tasked with supporting his widowed mother, who outlived her husband by a further 37 years.

Cromwell relocated to the Cambridgeshire town of St Ives in 1631 and then to Ely in 1636 following the inheritance of property from his maternal uncle. The rise in status which the inheritance provided, along with a commitment to the puritan way of life as a result of Cromwell’s self declared ‘spiritual awakening’ in the 1630s, arrived during a time of extreme political and religious unrest in England. However, whilst Cromwell became an MP for Cambridge he was not significantly involved in national politics until the 1640s.

Military and Political Leader

The summer of 1642 saw the outbreak of the first English Civil War between the Royalists, the supporters of King Charles I who claimed that the King should have absolute power as his divine right as king, and the Parliamentarians who favoured a constitutional monarchy and later the abolition of the monarchy and the House of Lords completely.

Colloquially, Royalists were also called Cavaliers in reference to the Latin caballarius, meaning horseman and in Henry IV, Part 2 Shakespeare used the word to describe a haughty member of the gentry. Parliamentarians were referred to as ‘roundheads’ because many Puritan men wore their hair cropped in what would today be described as a ‘bowl cut’ in contrast to the long ringlets favoured by their royalist counterparts as dictated by courtly fashion of the day. Both names were used derisively by their opponents.

From the very beginning Cromwell was a committed member of the parliamentary army. He was swiftly promoted to second in command as lieutenant-general of the Eastern Association army, parliament’s largest and most effective regional army, followed by a further promotion to second in command of the newly formed main parliamentary army, the New Model Army in 1645.

ADVERTISEMENT

When Civil War once again flared up in 1648 Cromwell’s military successes meant that his political influence had greatly increased. December 1648 saw a split between those MPs who wished to continue to support the King and those such as Cromwell (known as the ‘rump parliament’) who felt that the only way to bring a halt to the civil wars was through Charles’ trial and execution. Indeed Cromwell was the third of 59 MPs to sign Charles’ death warrant.

Westminster Hall (above, left) where the trial of King Charles I took place, and his subsequent execution (above, right)

Following the King’s execution in 1649, The Commonwealth of England was introduced and lead by a Council of State to replace the monarchy. Cromwell led the English military campaigns to establish control of Ireland in 1649 and later Scotland in 1650. This resulted in the end of the Civil War with a Parliamentary victory at the Battle of Worcester on 3 September 1651 and the introduction of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland. Cromwell was appointment to Lord General, effectively commander in chief, of the parliamentary armed forces in 1650.

In December 1653, Cromwell became Lord Protector, a role in which he remained until his death five years later. Whilst he later rejected Parliament’s offer of the crown, preferring to describe himself as a ‘constable or watchman’ of the Commonwealth, Cromwell’s role as the first Lord Protector was akin to that of a monarch involving “the chief magistracy and the administration of government”. However, the Instrument of Government constitution decreed that he must receive a majority vote from the Council of State should he wish to call or dissolve a parliament, thus establishing the precedent that an English monarch cannot govern without Parliament’s consent, which is still upheld today.

Death and Execution

It is thought that Cromwell suffered from kidney stones or similar urinary/kidney complaints and in 1658 in the aftermath of malarial fever Cromwell was once again struck down with a urinary infection, which saw his decline and eventual death at the age of 59 on Friday 3 September. Co-incidentally this was also the anniversary of his victories at Worcester and the Scottish town of Dunbar during the Scottish campaign of 1650-51. It is thought that Cromwell’s death was caused by septicemia brought on by the infection, although his grief following the death of his supposed favourite daughter Elizabeth the previous month from what is thought to be cancer certainly contributed to his rapid decline. Both Cromwell and his daughter received an elaborate ceremony (Cromwell’s funeral was based on that of King James I) and buried in a newly-created vault in Henry VII’s chapel at Westminster Abbey.

It is thought that Cromwell suffered from kidney stones or similar urinary/kidney complaints and in 1658 in the aftermath of malarial fever Cromwell was once again struck down with a urinary infection, which saw his decline and eventual death at the age of 59 on Friday 3 September. Co-incidentally this was also the anniversary of his victories at Worcester and the Scottish town of Dunbar during the Scottish campaign of 1650-51. It is thought that Cromwell’s death was caused by septicemia brought on by the infection, although his grief following the death of his supposed favourite daughter Elizabeth the previous month from what is thought to be cancer certainly contributed to his rapid decline. Both Cromwell and his daughter received an elaborate ceremony (Cromwell’s funeral was based on that of King James I) and buried in a newly-created vault in Henry VII’s chapel at Westminster Abbey.

Following Cromwell’s death his son Richard succeeded him to become Lord Protector. However, Richard lacked the political and military power of his father and his forced resignation in May 1659 effectively ended the Protectorate. The lack of a clear Commonwealth leadership lead to the restoration of Parliament and the monarchy in 1660 under Charles II.

On 30 January 1661, Oliver Cromwell’s body, along with that of John Bradshaw, President of the High Court of Justice for the trial of King Charles I and Henry Ireton, Cromwell’s son-in-law and general in the Parliamentary army during the English Civil War, were removed from Westminster Abbey to be posthumously tried for high treason and ‘executed’. This symbolic date was chosen to coincide with the execution of Charles I twelve years previously. The three bodies were hung from the Tyburn gallows in chains before being beheaded at sunset. The bodies were then thrown in a common grave and the heads were displayed on a twenty foot spike at Westminster Hall, where they remained until 1685 when a storm caused the spike to break, tossing the heads to the ground below.

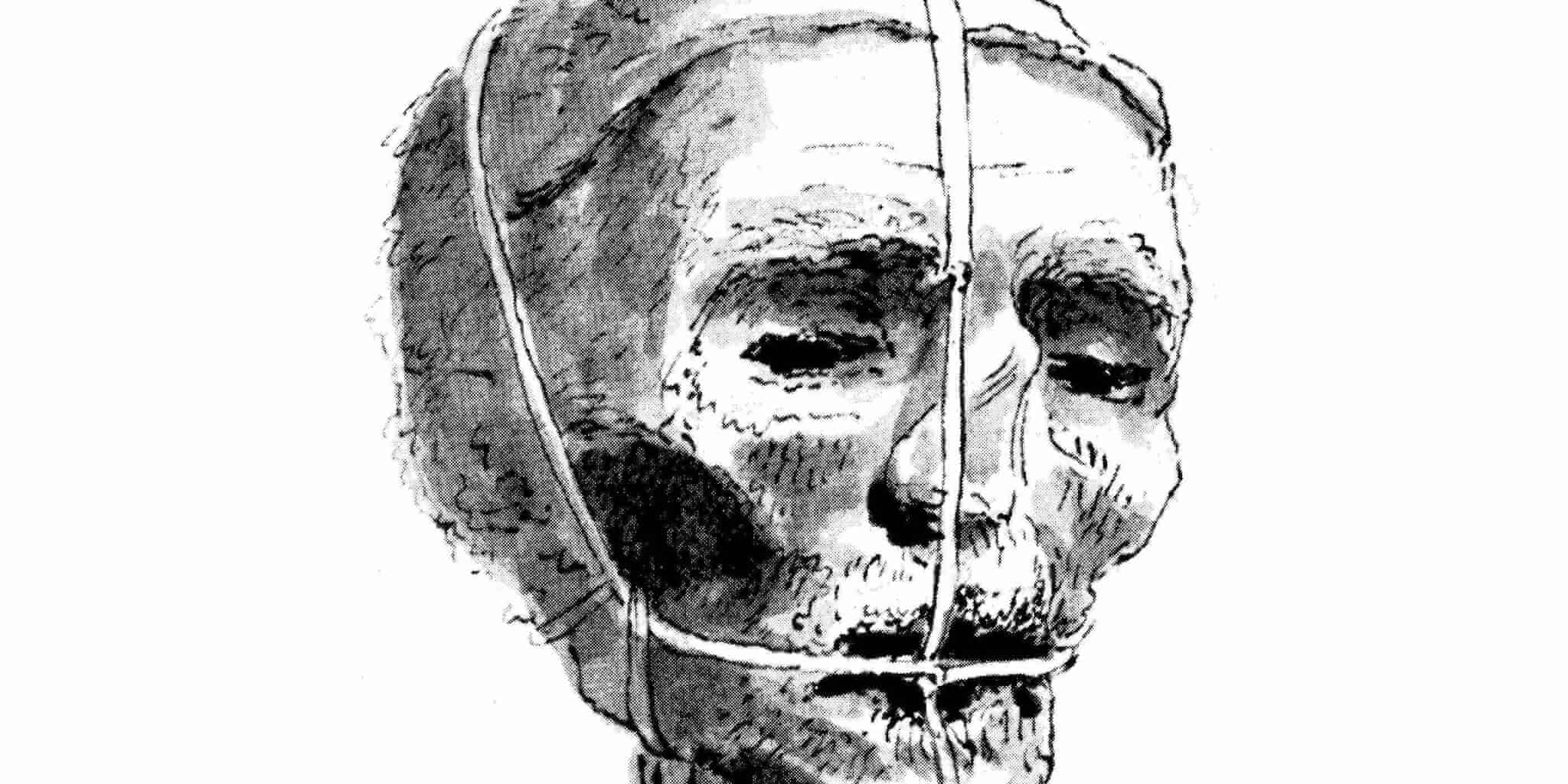

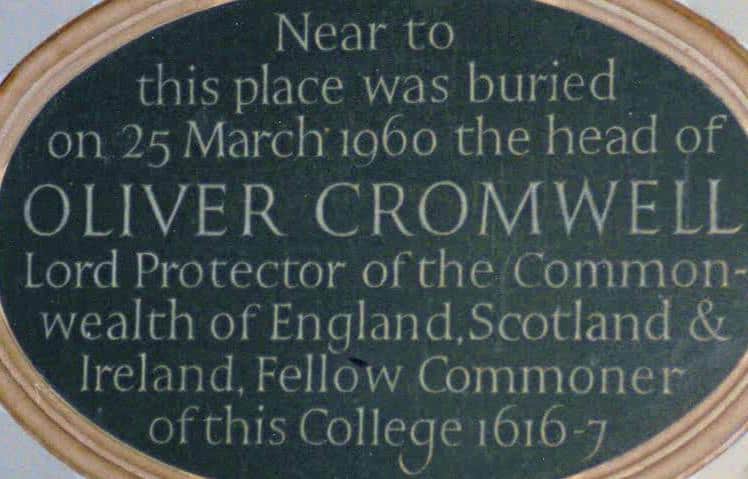

Unusually, at the time of Charles I’s execution Cromwell had allowed the King’s head to be sewn back on to his body to allow his family to pay their last respects to the corpse. Cromwell’s own head was found by a soldier who hid it in his chimney. On his deathbed, he bequeathed the relic to his daughter. In 1710 the head appeared in a ‘Freak Show’, described as ‘The Monster’s Head’. For many years the head passed through numerous hands, the value increasing with each transaction until a Dr. Wilkinson bought it. The head was offered by the Wilkinson family to his Alma Mater, Sydney Sussex College in 1960. It was given a dignified burial in a secret place in the college grounds.

It is said that Cromwell’s daughter Elizabeth, his supposed favourite child, had used her influence over her father to seek mercy for several royalist plotters and prisoners during the Civil War. It is thought that her intercessions on behalf of the royalists were taken into account when most Cromwellians were removed from Westminster Abbey because her body was not exhumed during the Restoration, although her final resting place in the Cromwell vault is now shared with Charles II’s illegitimate descendants!

Popular culture

Despite his death over 350 years ago, to this day Cromwell continues to provoke a strong reaction following his significant role in a dramatic and troubled period of British history. He has prompted numerous monuments, films, television and radio programmes and been broadly referenced throughout popular culture, from being the codeword to warn of an imminent German invasion of Britain in 1940 to Monty Python’s 1989 Oliver Cromwell and more recently the 2004 single by Morrissey, Irish Blood, English Heart. However Winston Churchill’s suggestion to name the British battleship HMS Oliver Cromwell when he was First Lord of the Admiralty did not gain royal approval, funnily enough!