The Interregnum, the word used to describe the period marking the republican government of England was an eventful and momentous time to be alive but what do we know about what life was really like during this time?

The period began with the execution of Charles I in January 1649, ushering in a Commonwealth period in English politics with Oliver Cromwell at the helm.

The English Civil War had divided communities between those who supported traditional monarchy and those who supported the parliamentarians. In the end, Cromwell and his forces managed to suppress any last ditch efforts to overthrow the growing tide of republican support and Charles I’s son was subsequently forced into exile on the continent.

The eleven years that followed would mark the beginning of not only a political experiment which embraced republicanism and shunned traditional English forms of governance, but also, a social, cultural and religious experiment which recalibrated expectations and reinforced Puritan values. The result of which would have enormous ramifications on some of our best loved traditions, none more so than the celebration of Christmas!

With the advent of parliamentary victory in the English Civil War, the catharsis that was achieved following such a win was the enforcement of more Puritan dominated views which emphasised the value of living a simple life free from the indulgence associated with Charles I’s reign. As part of this newly advocated lifestyle, dates on the social and cultural calendar of medieval England were suppressed as Christmas and Easter were first on the list for a Puritanical purge.

In medieval England Christmas had been an important part of the year, much like it is today!

The combination of religious observance, the attendance of Church and traditions of decoration within the home were all part and parcel of the festivities. 25th December was a holy day in which the birth of Jesus was commemorated and as such, celebrations would last until the 5th January with the Twelfth Night marking the coming of the Epiphany.

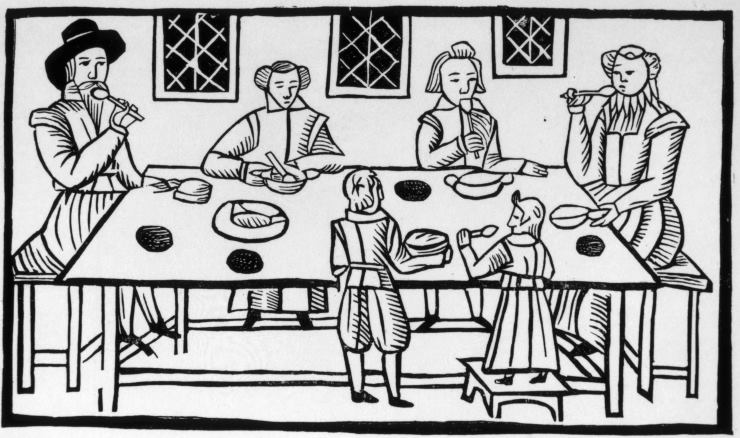

Christmas was a time of the year where merriment and celebrations brought communities together in church services, tavern knees-ups and big family and friend celebrations. The home was adorned with traditional decorations consisting of holly, ivy and mistletoe and festive food for those who could afford it included favourites such as turkey, mince pies and yummy puddings.

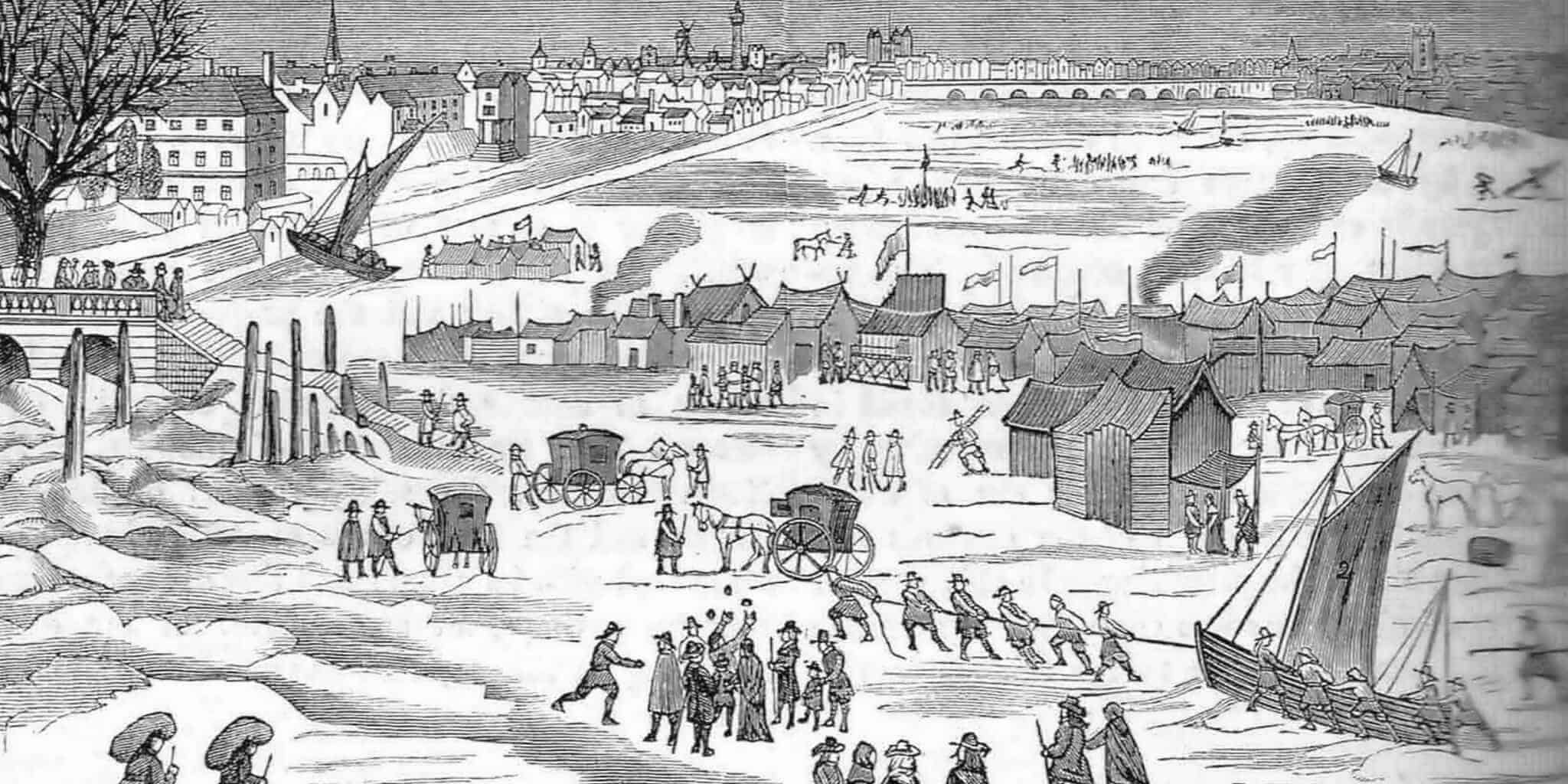

Whilst the level of celebrations varied depending on your budget, Christmas Day was a public holiday whereby, whether you lived in an isolated village community or in the centre of the hustle and bustle of London, special food and drink, merriment and gatherings unrestricted by usual rules for the rest of the year were the order of the day.

Whilst businesses closed early, communal festive celebrations might include the precursor to the modern pantomime, staged to entertain the family. Moreover, in an ambiance of medieval jubilance, singing was high on the agenda. Unfortunately, in the Interregnum period, all this was about to come to an end.

The austerity propagated during this period was in direct contrast to the indulgences associated with the festive time of year. Not only were Christmas and Easter in the firing line, but also a range of other cultural aspects of medieval society including theatre. A new era of social interaction was being hastily introduced with the celebration of Christmas on the 25th December banned.

Such a direct attack on the religious holiday had been brewing for some time; even before the outbreak of the Civil War, the Long Parliament had begun to chip away at the festive celebrations. By the time Charles I was overthrown, the dominance of certain values made way for draconian religious legislation.

The new parliamentary platform created during this period gave a stronger voice to strict Puritans who wanted to enforce their ideals through the legal network. There had already been a growing discontent about the perceived frivolousness of celebrations and the way in which this religious festival was being celebrated long before the Interregnum.

One such figure who had strong views on this matter included the pamphleteer Philip Stubbs who produced “The Anatomie of Abuses” which castigated many established cultural traditions such as theatre, fashion and the consumption of alcohol. For those like Stubbs, the introduction of a new Directory for Public Worship in January 1645 was well-received as a framework for introducing strict religious observance based on Puritanical values.

Christmas Day was thus forbidden, alongside the prohibition of everything that came with it, including the yuletide joy of singing. For the Commonwealth, the roots of celebrating Christmas were linked to “popish” origins with Roman Catholicism still viewed with a keen sense of resentment, bitterness and paranoia at the time. Catholicism and all aspects of idolatry associated with the faith were viewed with suspicion and the Puritans within parliament argued strongly in favour of the abolition of such festivities which had been fashioned by several centuries of Catholic tradition.

In 1644, these strict ideas were put into practice by an Act of Parliament which banned the festivities and then three years later, the Long Parliament went further in confirming the abolition of the Christmas Feast. Meanwhile, the tradition of singing at Christmas was now viewed as more of a political act than as a form of celebration.

Whilst strict adherence to these laws was expected, it did not prove enough to suppress the festivities of men and women across the country. They would not be silenced by this religious diktat, rather they were forced to carry out their celebrations in a clandestine manner, marked by secret singing and services. Carol singing whilst legally silenced still echoed underground, such was the will and desire to observe centuries of happy tradition.

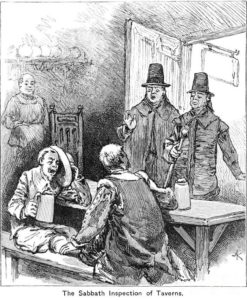

By 1656 even stricter measures were introduced to curb the flouting of rules, even going so far as to have soldiers patrolling the streets of London to ensure no-one was buying food traditionally associated with the Christmas feast. Whilst Sunday was seen as a holy day, Christmas by contrast was supposed to function much like any other, with shops and marketplaces being told to remain open.

Much legislation was passed during the Interregnum as a means to encourage the general public to fall in line with Puritan ideals and reject traditions which were steeped in Catholic forms of worship and religious observance. Through draconian measures of enforced austerity, the abolition of singing, feasts and nativities continued until the Restoration of 1660.

With all forms of celebration associated with Christmas banned, this Puritan inspired prohibition did not win the popular vote of the general public and incited pro-Christmas riots and blatant flouting of the rules leading to confrontations in a number of cities including Canterbury, London and Norwich.

Cromwell, the figure most synonymous with this period, was in power for much of the time these values were forced on the public. Whilst such strict cultural legislation is often directly associated with him personally, it was not in fact he who had initiated the ban, rather the Commonwealth parliament which had seen fit to invoke such widespread prohibition. If anything, Cromwell proved to be somewhat of a moderate force when it came to the abolition of Christmas; nevertheless, in his role as Lord Protector from 1653 onwards, he presided over these measures which actively tried to alter the cultural and social interactions of the public.

Despite the best efforts of the Puritanical elements of the republic, the will of the English people to celebrate could not be suppressed and by 1660, with the future of the Commonwealth looking more fragile by the second, these austere values no longer found a place in English society.

The severity of the period was now void and Christmas once more triumphed in the face of suppression. Celebration could now be observed freely and Christmas carols, many of which we continue to sing today were sung with glee.

This was not only a triumph for Christmas and all the festive joy it brings, but also a triumph for celebration, culture, tradition and community.

Christmas was back for good!!!!

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 28th November 2020