Devoted wife, Spanish royalty, English Queen Consort and power behind the throne are just some of the descriptions one could use when describing the medieval queen and wife of Edward I, Eleanor of Castile.

An arranged marriage of the Middle Ages did not often result in a happy union, however this was the exception to the rule. Eleanor of Castile and Edward I’s betrothal not only cemented important political alliances by confirming English sovereignty over Gascony, but in the long run created a successful royal partnership.

The story of this sometimes overlooked royal begins in Burgos in 1241. Born Leonor, named after her great-grandmother, she became known as Eleanor. Born into royalty, the daughter of Ferdinand III of Castile and his wife, Joan, Countess of Ponthieu, she had in fact much royal lineage as the descendant of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henry II of England.

In her youth she would benefit from a high standard of education, unusual for the time; her later responsibilities as queen would demonstrate this cultured beginning.

Meanwhile, whilst she was still very young her future marriage was being arranged, not to Edward I of England but to Theobald II of Navarre. Eleanor’s brother Alfonso X of Castile had hoped this marriage would allow a claim on Navarre, as Theobald was still not of age. Nevertheless, Theobald’s mother, Margaret of Bourbon had other ideas as she forged an alliance with James I of Aragon, blighting any chance of Eleanor’s marriage to her son.

Despite this initial setback, Eleanor’s prospects for making a successful marriage was still possible. This time her brother turned his attentions towards another area of possible ancestral claim, Gascony.

With much at stake for Henry III of England, the two parties entered into negotiations, eventually agreeing to Eleanor’s marriage to Edward with the inclusion that the Gascony claims would be passed on to Edward.

This was a critical alliance brokered by Henry III who subsequently allowed Edward to be knighted by Alfonso. This agreement would later be cemented by yet another marriage, this time Henry III’s daughter Beatrice to Alfonso’s brother.

With all the preparations already agreed upon by their families, Edward and Eleanor, who was only in her early teens, married in November 1254 in Burgos, Spain. As distant relatives with royal bloodlines and important family connections the two were the ideal match for such an arrangement.

After their marriage they spent a year in Gascony where Eleanor gave birth to her first child who sadly did not survive infancy. After just a year spent in France, Eleanor went to England, closely followed by Edward. However her arrival was not welcomed by all.

Whilst Henry III had been content with the negotiations ensuring English sovereignty over Gascony in southwest France, others had grown concerned that Eleanor’s relatives would take advantage as relations between the two royal families had not always been so cordial, especially since Eleanor’s mother had been rejected as a marriage prospect by Henry III.

Despite the circumstances, Edward was believed to have remained faithful to his Spanish queen, which was unusual for the time, and chose to spend much of his time accompanied by her, another anomaly for a medieval royal marriage.

So much so that Eleanor even accompanied Edward on his military campaigns, most surprisingly whilst she was pregnant with the future Edward II, to whom she gave birth at Caernarfon Castle whilst her husband quelled signs of rebellion in Wales. Their son Edward became the first Prince of Wales.

Eleanor was unlike many of her counterparts as queen consort; she was highly educated, interested in military affairs and had a keen eye for all things cultural and economic.

Her influence would prove to have an impact on her husband as well as the nation as her Castilian style would influence far-ranging domestic aesthetics, from horticultural design to tapestries and carpet design. This new style began to seep into the homes of the upper classes who embraced the new fashion of tapestries and fine tableware, demonstrating her cultural impact on the higher echelons of English society.

Moreover, as an intellectual and highly-educated woman, she found herself a patroness of literature, showing herself to have a wide variety of interests. She employed scribes to maintain the only royal scriptorium of Northern Europe at the time, as well as commissioning a variety of new works.

Whilst her influence on the domestic sphere was noteworthy, she was also heavily involved in finance, as initiated by Edward himself.

Her involvement with land acquisition between 1274 and 1290 led her to accrue a number of estates worth, around £3000. With her landholdings, Edward wanted to ensure financial security for his wife without drawing on much needed government funds.

Nevertheless, the way in which these estates were acquired did not help her popularity. Taking over debts of Christian landlords owed to Jewish moneylenders, she subsequently offered to cancel the debts in exchange for land pledges. Her association with such an arrangement however inevitably led to scandalous gossip, with even the Archbishop of Canterbury warning her about her involvement.

During her lifetime, her business dealings did not help her gain popularity, however her sphere of influence was growing. Her military involvement was both astounding and unusual, with Eleanor choosing to accompany Edward on many of his military manoeuvres.

In the midst of the Second Barons’ War, Eleanor supported and contributed to Edward’s war efforts by bringing over archers from Ponthieu in France. Furthermore, she remained in England during the conflict, maintaining control over Windsor Castle whilst Simon de Montfort ordered her removal in June 1264 upon hearing rumours about Eleanor’s call for troops to be brought in from Castile to contribute to the royalist war effort.

Whilst her husband had been captured during his defeat at the Battle of Lewes, Eleanor was held at Westminster Palace, until royalists forces were finally able to overcome the barons at the Battle of Evesham in 1265. From then on, Edward would play a more substantial role in government with his wife alongside him.

There is still much speculation over how much of a role she played in political affairs, with her influence extending to her daughter’s prospective marriages. Moreover, her influence may not have been quite so formal but there appear to be indications in some of Edward’s policy-making choices which mirror that of the Castilian choices back in Eleanor’s home country.

Edward also continued to uphold, as much as he could, his obligations to Eleanor’s half-brother Alfonso X.

Whilst Edward’s military escapades took him far and wide, Eleanor became a loyal companion, so much so that in 1270 Eleanor accompanied Edward on the Eighth Crusade in order to join his uncle Louis IX. However Louis died in Carthage before they arrived. In the following year, upon the couple’s arrival in Acre, Palestine, Eleanor gave birth to a daughter.

In her time spent in Palestine, whilst she could not have an overtly political role in the proceedings she did have a copy of ‘De re militari’ translated for Edward. A treatise by the Roman Vegetius, it contained something of a military guide to warfare and the principles of fighting which would have been most useful for Edward and his medieval crusading compatriots.

Meanwhile, the presence of Edward in Acre led to an assassination attempt, leading to a serious wound inflicted by what was believed to be a poisoned dagger, leaving him with a dangerous wound on his arm.

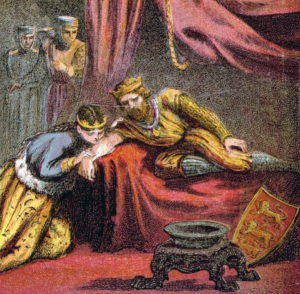

Whilst Edward was able to recover thanks to the surgeon who was on hand to cut away the infected flesh from the wound, a more dramatic version of events has since been told. The story tells the tale of Eleanor, sensing her husband’s impending mortality, risking her life by sucking the poison out from his arm and saving her husband. Such a fanciful tale could be found more likely in a novel.

Once fully recovered, the united couple returned to England which had been governed by a royal council since Edward’s father, Henry III had passed away. A year later, Edward and Eleanor were crowned King and Queen Consort on 19th August 1274.

As King Edward I and Queen consort, they were believed to have lived in a convivial and happy relationship, both fulfilling their respective roles. As her fluency in English was questionable, much of her communication was in French. At the time, the English court was still bilingual.

During her time as queen she dedicated herself to charitable causes and was a patron of the Dominican Orders friars. Her influence extended to the arrangement of certain marriages which were carefully orchestrated, helping to sustain good diplomatic relations, all with the full support of her husband.

However her health began to decline as she began to make arrangements for the marriages of her two daughters. Sadly, whilst on a tour she eventually succumbed to her failing health in Harby, Nottinghamshire. She passed away with Edward at her bedside on 28th November 1290.

It would be another ten years before Edward remarried and in a touching tribute to his first wife, had his daughter named after Eleanor.

In a palpable display of his grief and undying affection for Eleanor, he commissioned the creation of twelve elaborate stone crosses known familiarly as Eleanor Crosses. A touching tribute to a loyal wife.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.