Out at sea loomed the 138 ships of the mighty Spanish Armada. On the Hoe in Plymouth, Sir Francis Drake shrugged and finished his bowls match before drumming up his men and setting out to drub the enemy. In all British history, there are few events that have achieved such iconic status. The tale of Drake defeating the Armada has accumulated myth and legend like an old ship that hasn’t had the barnacles scraped off its bottom for centuries.

It’s a great story, too. Yet Drake was only second in command after Lord High Admiral the 2nd Baron Howard of Effingham. Many of the Spanish ships were only technically Spanish. They came from all over the Mediterranean, Portugal and even northern Germany, and carried crews of equally diverse origins. They weren’t all galleons, either. There’s also a strong case for it being the weather that really finished off the would-be invasion force, blown hither and yon by a violent storm that took the ships to the north right round the coasts of Britain and Ireland. Many survived, and so did their crews.

Along with the rest of the Armada legends, there’s a persistent story about Spanish stallions swimming exhaustedly ashore from the storm-tossed ships to dally with the local mares. Thus, goes the tale, the Galloway, Eriskay, and HIghland landraces of Scotland were founded, along with the Connemara pony in Ireland. However, there were no stallions on the ships of the Spanish Armada, just a few pack animals that all appear to have been lost overboard in the storm. The cavalry was waiting in the Low Countries for word from the invasion force that they would be carried across the Channel to triumphantly ride into vanquished London. (Cue Monty Python style insults hurled at the English from the sailors on board the ships.)

The Spanish stallions story was efficiently debunked by Robert Beck in his book on the Eriskay Pony in the 1990s, by the simple act of going to the Spanish consul and asking to see the bills of lading for the Armada ships. These confirmed there were no stallions on board. Yet the legend persists, because, understandably, people really don’t want to give up such a romantic tale. I’ve had to refute it at talks on the Galloway Horse as recently as 2024.

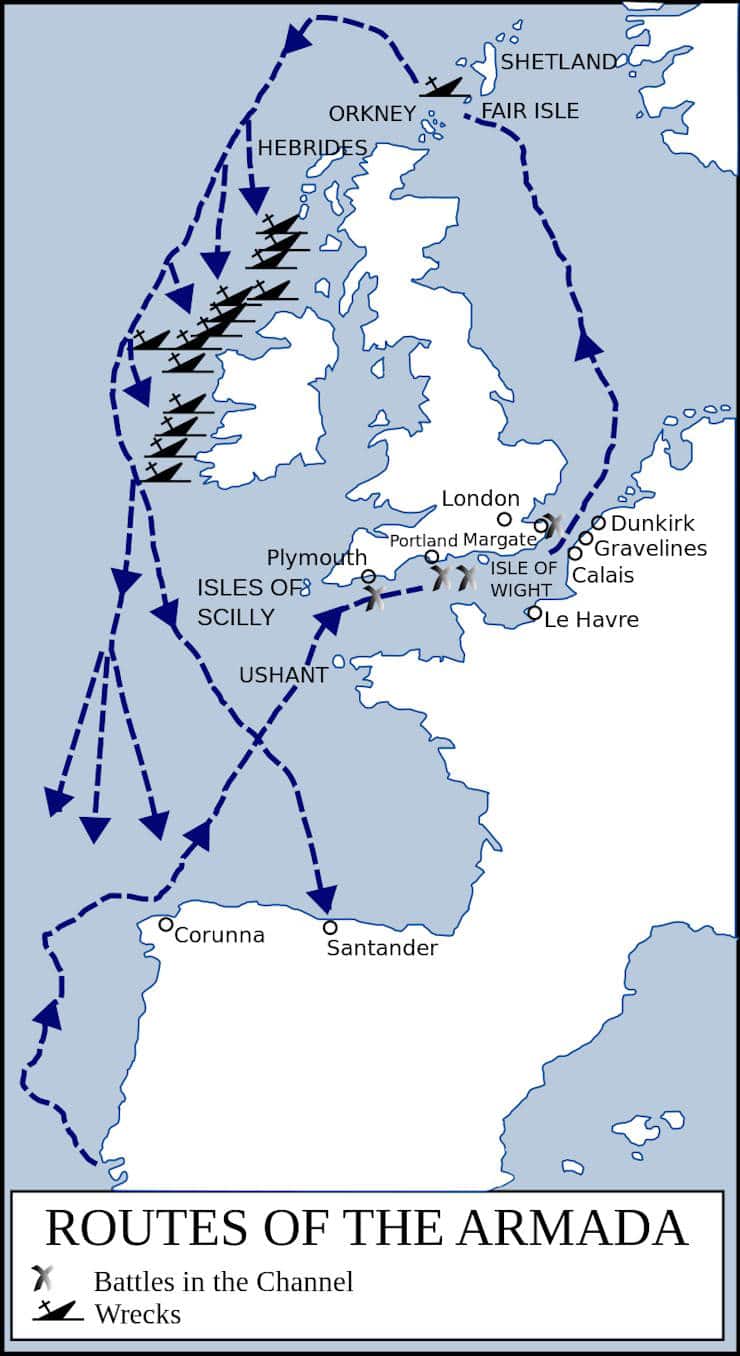

A glance at the map taken by the wind-blown Spanish force shows the impossibility of the story. The ships were carried past Orkney and the Hebrides, some continued round the west coast of Ireland, being wrecked on the Irish coastline. The non-existent stallions would have had to do quite some swimming to make landfall in places like Galloway in southwest Scotland. The one Spanish ship that did make contact with the Scottish coast is well documented, and that vessel is now known as the Tobermory Galleon, a wreck off the coast of Mull.

To begin with the romance: take one Spanish princess, a handsome local chieftain, and a jealous wife; add a heap of alluring Spanish gold, some supernatural cats and malevolent witches; season with an English spy or two, and stir into an explosive mix. The Armada vessel that would become persistently known as the Tobermory Galleon limped into Tobermory Bay in October 1588, seeking shelter and repairs. For various reasons to be outlined shortly, the ship came be called, incorrectly, the Florencia or Florencio, and also the Florida. And of course, it had to have gold on board, because which romantic soon-to-be wrecked Spanish vessel did not?

Local authority was vested in Lachlan Maclean of Duart, also known as Lachan Mór, “Big Lachlan”, who provided aid to the ship and its captain, apparently with a view to appropriating the ship and its crew for his own use in raiding the castle of the rival Mcdonalds. The fact that the ship was supposed to be carrying payment for the Armada fleet may have been a bonus. Alternative version: the ship contained a beautiful Spanish princess who was sailing the coasts of Europe in search of the love of her life, whom she had seen in a dream. On finally reaching Tobermory Bay she found him in the form of Maclean of Duart, whose jealous wife took supernatural revenge.

The local witches, many of whom considered themselves to be Mcleans, were well-known for their power (“Anything cursed, and at a reasonable price)”, and Lady Mclean found one who would conjure up a mob of paranormal cats to visit the ship. Quite what the witch and the cats had in mind is unclear, but certainly some nasty sharpening of claws on Spanish ship timbers and slashing of doublets was likely to be included.

This is where romance meets reality. The ship unexpectedly blew up. There were various suggestions as to why this had happened, but those who favour a supernatural cause reckon that it was sparks from the tail of one of the demon cats in the powder room. The remains of the vessel sank to the bottom of Tobermory Bay. This only enhanced its legendary reputation, and over the years many attempts were made to find the gold which was said to be there.

Thus, the legend. A good place to start for some facts, rather than romance, is the Scottish website that lists all Scotland’s sites of historic interest: Canmore. Here, the Florence, or Florida, sometimes known as the San Francisco, is revealed for what it truly was: not a romantic Spanish galleon, but a working vessel from Ragusa (now Dubrovnik in Croatia) commandeered by the Spanish authorities for the Armada. Originally, she was a grain carrier, and her task in the Armada was transporting goods such as weaponry and probably other stores, as well as soldiers. In terms of ship category, she was a carrick, not a galleon.

Taken to Sicily, she was apparently renamed San Juan de Sicilia, before becoming the Santa Maria De Gracia Y San Juan Bautisa, a much more impressive name. This also put the vessel under the protection of the two saints in readiness for her military role. The ship was carrying 26 guns, 63 marines, and 279 soldiers, and was under the command of Don Diego Tellez Enriquez. Luka Ivanov Kinkovic was master of the ship, just as he had been in her Ragusa days. The name “Florencia” was given to the ship by later writers due to a misunderstanding that it was provided to the Armada by the Duke of Florence.

The explosion that sank the vessel is more prosaically put down to mishandling of the gunpowder. Other sources attribute the explosion to Lachlan Mclean, perhaps wanting to make overtures to the English. However, a body of research suggests the Dumbarton resident John Smollett, who was believed to be an English agent, was responsible. The English authorities were unlikely to want a restored Spanish vessel lurking around the coasts and the fact that Mclean of Duart appropriated the men on board for his own military use adds plausibility to the story. Most of the crew, apparently, were not on board when it exploded, but at Duart Castle. Tobias Smollett, the writer, claimed John Smollett as an ancestor and endorsed the story.

The afterlife of the sunken vessel is in many ways the most interesting part of the story. The ship now firmly established as the Tobermory Galleon attracted treasure hunters like a magnet. As early as the late seventeenth century, diving bells were going down to inspect the wreck and bring back anything they could find. Chests of gold proved elusive, but there were cannon and cannon balls on board. Plates, candlesticks, pottery and bits of timber, plus the occasional coin, were popular among collectors. Walter Scott visited and took some timber fragments from the wreck away with him. It proved an important location for trying out many kinds of technology and salvage methods.

The wreck site has been managed by the family of the Dukes of Argyll, as Admirals of the Western Isles, for centuries. In 1954 a navy diving team brought back a skull and other items. Researcher Sophia Kingshill noted in an address to the Folklore Society that “a local hotelier wanted to fix [the skull] to his wall. When he tried to bore a hole in it he started to get blinding headaches, and eventually the skull was thrown back into the sea”. Many non-cursed items relating to the history of the wreck can be seen today in Inveraray Castle archives and the Mull Museum.

The most swashbuckling of all the investigation and recovery teams must surely be the American-led ”Pieces of Eight Syndicate”, which was very active in the early decades of the twentieth century. At great expense and no little damage to the seafloor, the team appears to have achieved next-to-nothing.

So there we have it. The Tobermory Galleon was not a Spanish ship, and not a galleon, had no vast store of gold on board, was not called the Florence or Florencia, carried no lovelorn Spanish princess, and was not set alight by the tail of a vengeful cat, or sunk by the witches of Mull. There were no Spanish stallions on board. Everything else, however, must be gloriously, romantically, true!

Dr Miriam Bibby FSA Scot FRHistS is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 21st April 2024