The Spanish Armada set sail from Spain in July 1588, with the mission of overthrowing the Protestant Queen Elizabeth I and restoring Catholic rule over England.

Many years previously in the early 1530s, under instruction from Elizabeth’s father King Henry VIII, the Protestant Church of England had broken away from the Pope and the Roman Catholic Church. After Henry died however, his eldest daughter Mary eventually succeeded him and in attempting to restore Catholicism to the country married King Philip II of Spain.

Philip’s marriage to Mary, daughter of Henry’s first wife Catharine of Aragon, was as far as he was concerned, fuelled by a religious zeal to father an heir that would eventually return England to the Catholic fold. The English Parliament had only countenanced their marriage on the basis that Philip was to be Mary’s consort and he was expressly forbidden from ruling the country and from becoming its king.

Philip’s marriage to Mary, daughter of Henry’s first wife Catharine of Aragon, was as far as he was concerned, fuelled by a religious zeal to father an heir that would eventually return England to the Catholic fold. The English Parliament had only countenanced their marriage on the basis that Philip was to be Mary’s consort and he was expressly forbidden from ruling the country and from becoming its king.

When Mary died childless in 1558, her very Protestant half-sister Elizabeth, daughter of Henry’s second wife Anne Boleyn, came to the throne. Philip’s precarious grasp on England appears to have loosened, until that is he had the bright idea of proposing marriage to Elizabeth as well.

Elizabeth then appears to have adopted some very clever delaying tactics …”Will I, or won’t I?” And whilst all this procrastination was going on on one side of the Atlantic, English ships captained by ‘pirates’ such as Drake, Frobisher and Hawkins were mercilessly plundering Spanish ships and territories in the Americas. To the English, Drake and his fellow ‘sea-dogs’ were heroes, but to the Spanish they were no more than privateers who went about their business of raiding and robbing with the full knowledge and approval of their queen.

Events finally came to a head between Elizabeth and Philip in the 1560s when Elizabeth openly supported Protestants in the Netherlands who were revolting against Spanish occupation. Holland wanted its independence from the occupying Spanish forces that had been using their religious secret police called the Inquisition to hunt out Protestants.

It is thought that Philip made his decision to invade England as early as 1584 and almost immediately started the construction of a massive armada of ships that could carry an army capable of conquering his Protestant enemy. He gained Papal support for his venture and even identified his daughter Isabella as the next Queen of England.

The preparation required for such a venture was huge. Cannons, guns, powder, swords and a whole host of other essential supplies were needed and the Spanish purchased these weapons of war on the open market from anybody that would sell them. With all this activity going on, it was very difficult for the Spanish to keep the Armada a secret, and indeed it may have been their intention to use some early ‘shock and awe’ tactics in order to worry their enemy.

Their tactics appear to have worked as in a bold preemptive strike, said to be against Elizabeth’s wishes, Sir Francis Drake decided to take matters into his own hands and sailed a small English fleet into the port of Cadiz, destroying and damaging several Spanish ships that were being built there. In addition, but just as significant, a huge stock of barrels was burned. These were intended to transport stores for the invading forces and their loss would affect essential food and water supplies.

ADVERTISEMENT

Mainland England was also being prepared for the arrival of the invading forces with a system of signal beacons that had been erected along the English and Welsh coasts in order to warn London that the Armada was approaching.

Elizabeth had also appointed Lord Howard of Effingham to command the English fleet, a leader considered strong enough to keep Drake, Hawkins and Frobisher under control.

After one false start in April, when the Armada had to return to port after being damaged by storms before they had even left their own waters, the Spanish fleet finally set sail in July 1588. Almost 130 ships had gathered with approximately 30,000 men on board. For moral and obviously spiritual support, their precious cargo also included 180 priests and some 14,000 barrels of wine.

Sailing in their classic crescent formation, with the larger and slower fighting galleons in the middle protected by the smaller more maneuverable vessels surrounding them, the Armada moved up through the Bay of Biscay.

Although the Armada had indeed set off, it was not initially bound for England. The plan devised by King Philip was for the fleet to pick up extra Spanish soldiers re-deployed from the Netherlands prior to invading England’s south coast. Following the recent death of Spain’s famous admiral Santa Cruz however, Philip had somehow made the strange decision to appoint the Duke of Medina Sidonia to command the Armada. An odd decision in that whilst he was considered a good and very competent general, Medina Sidonia had no experience at sea and apparently soon developed seasickness after leaving port.

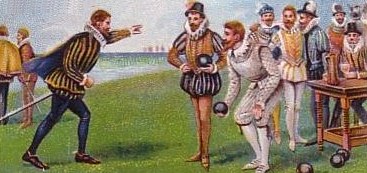

On 19th July, word came that the Armada had been sighted and so an English force led by Sir Francis Drake left Plymouth to meet it. It is said that when Drake was told of its approach, he simply replied that he had plenty of time to finish his game of bowls before defeating the Spanish. A touch bravado perhaps, or is just possible that he recognised that the tide was against him getting his ships out of Devonport harbour for an hour or two!

When Drake eventually did get his ships into the Channel however, there was little he could do to inflict much damage against the solid well built hulls of the Spanish ships. The crescent shaped sailing formation they adopted also proved very effective in ensuring that in the main, all Drake could achieve was to waste a lot of ammunition firing at the Armada.

After five days of constant cannon exchanges with Drakes ships the Spanish were now running desperately short of ammunition. In addition, Medina Sidonia had the extra complication that he also needed to pick up the extra troops he needed for the invasion from somewhere on the mainland. On 27th July the Spanish decided to anchor just off Gravelines, near modern day Calais, to wait for their troops to arrive.

The English were quick to exploit this vulnerable situation. Just after midnight eight “Hell Burners”, old ships loaded with anything that would burn, were set adrift into the resting and closely packed Armada. With ships made of wood sporting canvas sails and loaded with gunpowder the Spanish couldn’t help but recognise the devastation these fire-ships could cause. Amidst much confusion, many cut their anchor cables and sailed out to sea.

But as they broke into the dark of the Channel their crescent shaped defensive formation had disappeared and the Armada was now vulnerable to attack. The English did attack but they were bravely fought off by four Spanish galleons that were attempting to protect the rest of the fleeing Armada. Outnumbered ten to one, three of the galleons ultimately perished with significant loss of life.

The English fleet however, had assumed a position that blocked off any chance that the Armada could retreat back down the English Channel. And so, after the Spanish fleet had reassembled, it could only head in one direction, northwards to Scotland. From here, sailing past the west coast of Ireland they could perhaps make it home to Spain.

Attempting to sail northwards and away from trouble, the more agile English ships caused considerable damage to the retreating Armada.

With insufficient supplies, together with the onset of the harsh autumnal British weather, the omens were not good for the Spanish. Fresh water and food quickly disappeared and as the Armada rounded the north of Scotland in mid-September, it sailed into one of the worst storms to hit that coast in years. Without anchor cables the Spanish ships were unable to take shelter from the storms and as a consequence many were dashed on to the rocks with great loss of life.

The ships that survived the storm headed for what should have been a friendly Catholic Ireland in order to re-supply for their journey home to Spain. Taking shelter in what is now called Armada Bay, just south of Galway, the starving Spanish sailors went ashore to experience that famous Irish hospitality. Immigration control was apparently short and swift, with all who went ashore attacked and killed.

The ships that survived the storm headed for what should have been a friendly Catholic Ireland in order to re-supply for their journey home to Spain. Taking shelter in what is now called Armada Bay, just south of Galway, the starving Spanish sailors went ashore to experience that famous Irish hospitality. Immigration control was apparently short and swift, with all who went ashore attacked and killed.

When the tattered Armada eventually returned to Spain, it had lost half its ships and three-quarters of its men, over 20,000 Spanish sailors and soldiers had been killed. On the other side the English lost no ships and only 100 men in battle. A grim statistic of the time however, records that over 7,000 English sailors died from diseases such as dysentery and typhus. They had hardly left the comfort of English waters.

And for those English sailors who did survive, they were poorly treated by the government of the day. Many were given only enough money for their journey home, with some receiving only part of the pay due to them. The commander of the English fleet Lord Howard of Effingham, was shocked by their treatment claiming that “I would rather have never a penny in the world, than they (his sailors) should lack…” He apparently used his own money to pay his men.

The victory over the Armada was greeted throughout England as divine approval for the Protestant cause and the storms that ravaged the Armada as divine intervention by God. Church services were held through the length and breadth of the country to give thanks for this famous victory and a commemorative medal was struck, which read, “God blew and they were scattered”.