One of the most complex operations in the history of maritime archaeology was the raising of Henry VIII’s flagship, the Mary Rose, from the seabed of the Solent in 1982. The Mary Rose sank on 19th July 1545 while leading the attack against a huge French invasion fleet, much larger than that of the Spanish Armada forty-three years later. The French were attempting to capture Portsmouth and from there, to invade England.

Henry VIII had split from the Catholic Church in 1534. The Pope, furious, demanded that the Catholic monarchs Francis I of France and Charles V of Spain (nephew of Catherine of Aragon, Henry’s first wife) invade and remove Henry from power. However in 1544 Henry VIII allied with Charles and declared war on France. Having captured Boulogne, Charles then betrayed Henry by negotiating a truce with Francis. On 3rd January 1545 Francis announced his intention to invade England, ’to liberate the English from the Protestant tyranny that Henry VIII had imposed on them’. Francis was taking advantage of the fact that the English armies were otherwise occupied in Ireland, France and Scotland. His target was Portsmouth, Henry’s naval base.

In May 1545, the French assembled a large fleet in the estuary of the River Seine and on 16th July the huge French force under the command of Admiral Claude d’Annebault set sail for England. Expecting the invasion, King Henry and his Privy Council came to Portsmouth.

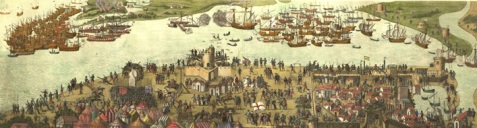

On 18th July the French fleet entered the Solent unopposed with 150 warships, 25 war galleys and over 30,000 troops ready to attack Portsmouth and the coast. The English had around 80 ships, including the flagship Mary Rose and the Great Harry. Vastly outnumbered, the English fleet sheltered in the heavily defended Portsmouth Harbour.

With King Henry watching from Southsea Castle, the French began their attack. 25 galleys, each with a single huge cannon in the bow, moved in on the English fleet in Portsmouth Harbour. The French were however soon chased off by the English rowbarges and little damage was done.

Detail of the Cowdray Engraving showing the sinking of the Mary Rose on 19th July 1545

19th July was a calm day with little wind, and the attack continued off Spithead with the French using their galleys against the less maneuverable English ships. The greatest loss of the battle was that of the Mary Rose. It is thought that having fired a volley from one side of the ship, she was turning when a sudden gust of wind made her suddenly heel over to her side. Water rushed in through the open gunports and she sank quickly.* Out of a crew of at least 400, fewer than 35 escaped.

Late in the afternoon the wind picked up again and the English were able to beat off the French galleys. Unable to get an advantage at sea, the French invaded the Isle of Wight.

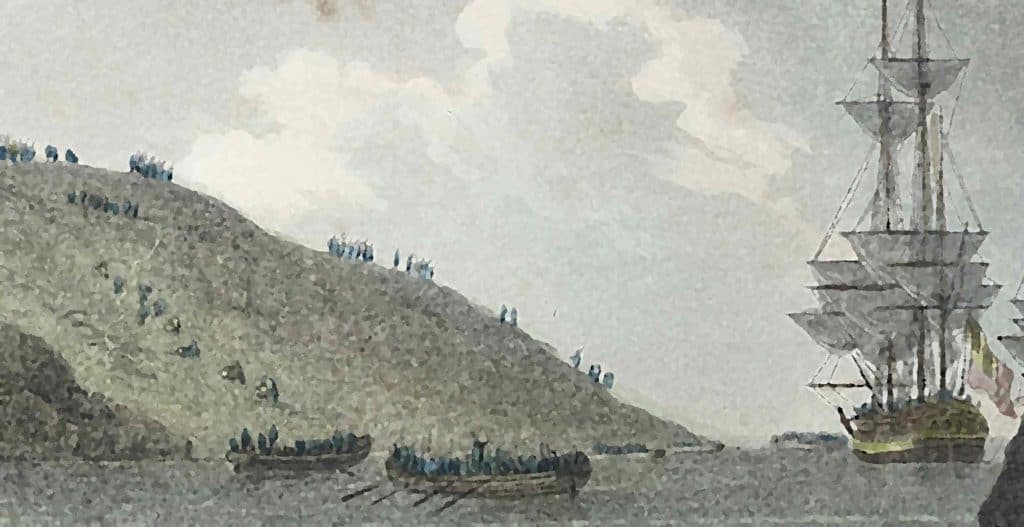

The Cowdray engraving of the Battle of the Solent, 1545.

The island’s population was only about 9,000. They were greatly outnumbered by the French force and so should have been easily overcome. However, because of the frequent raids and invasions by the French during the Hundred Years War, the islanders were well prepared. All the men underwent compulsory military training and some women were even trained as archers.

The French admiral ordered three attacks on the island, at St Helens, Bonchurch, and Sandown. The cannon at the small fort at St Helens had been bombarding the French fleet but was easily captured. The remaining English forces in the area were forced to retreat while the French laid waste to the villages of Bembridge, Seaview, St Helens and Nettleston.

A larger force landed at Bonchurch. The French landing was unopposed and the invaders advanced inland. The defenders managed to drive back the first French attack, but after the second assault, the outnumbered English and local militia turned tail and fled the battle. The English commander, Captain Robert Fischer was too fat to run and is reported to have cried out offering £100 for anyone who could bring him a horse. Believed to have perished in the battle, his last words may have inspired William Shakespeare in his play ’Richard III’, where Richard cries ‘A horse! A horse! My kingdom for a horse!’

The third French attack was at Sandown Castle, then in the last stages of completion. The French landed successfully but before they could dig in, the local forces rushed to the beach. A fierce battle broke out on the beaches and cliffs around the castle. Their leaders wounded, the French retreated back to their ships. The event is commemorated by a plaque in Seaview that reads, ’During the last invasion of this country, hundreds of French troops landed on the foreshore nearby. This armed invasion was bloodily defeated and repulsed by local militia 21st July 1545’.

Meanwhile a group of Frenchmen had landed to the north of Sandown Bay. Forced back to the ruins of Bembridge, they dug in and successfully held off the English. The French were now left with a dilemma. Should they leave their ships at anchor supporting their troops at Bembridge, or retreat? They did not have enough supplies or troops to successfully take the island, and the naval battle was at stalemate.

Only three days after the sinking of the Mary Rose, it was decided to abandon the invasion. The troops on the Isle of Wight were recalled and the French fleet finally departed on 28th July.

The lasting legacy from the battle, the Mary Rose, was raised from the Solent seabed in 1982 and is now on display at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard. Artefacts from the ship are also on display at the nearby Mary Rose Museum.

*Another theory is that she may have been fatally holed by a cannonball fired from a French galley.

Published: 9th March 2015