On 12th April 1587, Sir Francis Drake set sail from Plymouth on an expedition which would result in an attack on the harbour at Cádiz in southern Spain, destroying ships and supplies and ultimately forcing the Spanish Armada to delay sailing for an entire year. This incident became known as ‘Singeing the King of Spain’s beard’.

Francis Drake was a sea captain, privateer and one of England’s most prominent figures in maritime warfare. During his lifetime, he carried out voyages, expeditions, attacks and naval battles, most famously serving as the Vice Admiral during the battle against the Spanish Armada in 1588.

He was the second person and the first Englishman to complete a circumnavigation of the world in just one single expedition and served as captain during the voyage. Whilst sailing into the Pacific Ocean he laid claim to modern-day California and instigated an ensuing conflict with the Spanish on the American coastline. For his efforts and achievements Elizabeth I awarded Drake a knighthood in 1581.

His maritime career made him a hero in the eyes of the British whilst his main enemy at the time, the Spanish, referred to him as ‘El Draque’ and saw him as an English pirate. Such was his impact and reputation that King Philip II of Spain allegedly offered a reward amounting to around six million pounds for his capture or death. Drake was Spain’s nemesis and his raid on Cádiz in 1587 proved to be a crucial expedition in protecting Britain’s coastline and delaying the Spanish Armada for a year.

Francis Drake’s maritime escapades took place during a very tense political, economic and religious time. England and Spain found themselves in direct competition with one another, with religious friction coming to a head when Elizabeth I was excommunicated by Pope Pius V in 1570, whilst Philip II of Spain joined with the French Catholic League in producing a treaty whose sole aim was to eradicate the Protestant faith.

Politically there was much at stake. In 1585 England agreed through the Treaty of Nonsuch to form an Anglo-Dutch military alliance against Spain, the Dutch of course having been embroiled in the Eighty Years’ War with the sole aim of attaining independence.

England was also proving to be a serious threat to Spanish economic prosperity. English privateers were carrying out numerous raids on Spanish territories around the West Indies and against the Spanish treasure fleet. The territories being established in the Americas were essential for supporting the treasury back in Madrid.

From the English perspective, Spain’s growing imperial prominence on the global stage was proving to be a major threat. The Spanish Empire had gradually been acquiring wealth, prestige and power and in 1580 it entered a dynastic union with the kingdom of Portugal. The security threat to the English was high, with Spain also being bolstered by its support from the German Habsburgs and Italian princes.

The combination of political threats, economic competition and religious divergence came to a head in 1585 when the Anglo-Spanish War erupted, lasting until 1604. Philip II of Spain made plans for a great military fleet which gathered at the port of Cádiz. The aim of invading England was to be thwarted by none other than Francis Drake.

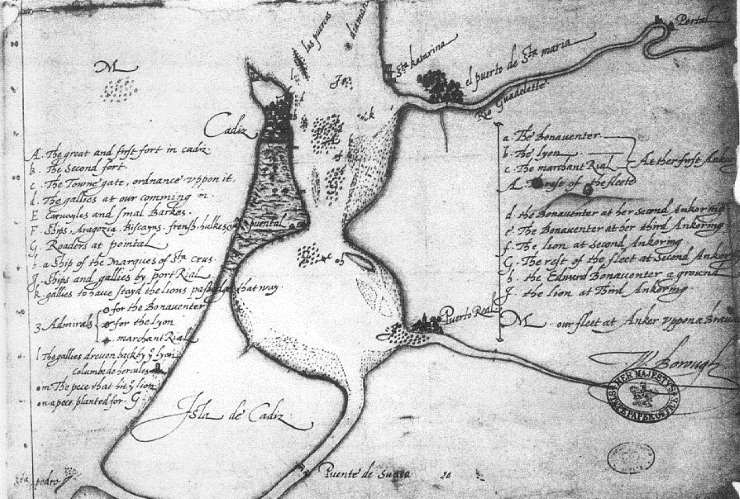

Drake’s mission, as instructed by Elizabeth I, was to inspect the maritime preparations of the Spanish, interfere with their supplies and launch an attack on their ships and ports. The naval expedition, headed by Drake, consisted of four Royal Navy galleons, with Drake commanding the Elizabeth Bonaventure. The ships’ value was held by the Queen herself who owned the vessels and received fifty percent of the profits, whilst the rest was made up from the money of London merchants.

The great expedition set sail from Plymouth in April 1587. Whilst the maritime journey was underway, the Queen was said to have sent a counter-command, not unusual for the time, which instructed Drake not to commence with any conflict against the Spanish. This was simply done as a precaution for the Queen, who could deny culpability should the naval voyage prove unsuccessful. Of course, Drake was never to receive the order and the ships continued sailing for the port of Cadiz.

In order for the attack to be executed as planned, the details of this surprise raid were top secret. Secrecy was paramount, so Elizabeth’s spymaster general, Sir Francis Walsingham assisted Drake’s plan by feeding misinformation about the voyage to the English ambassador in Paris, who was in the pay of the Spanish. This would therefore allow the plan to be carried out, giving the Spanish no warning.

Whilst the ships rounded the coast of Galicia in north-west Spain, bad weather was said to have delayed the journey somewhat, leading to the fleets regrouping and joining up with two Dutch ships, who brought with them important information regarding Spain’s preparations to amass a considerable war fleet from Cádiz.

Time was of the essence: the English fleet arrived at the Bay of Cádiz at dusk. Drake and his compatriots flew no flags and entered the port launching an attack on the unsuspecting Spanish fleet. The galleons in the port were under the command of Pedro de Acuña who initially sailed out to confront Drake and his ships, but was subsequently pushed back. The Spanish galleons proved no match for the English.

The Spanish retaliated with gunfire from the shoreline which led to the shelling of some of the fleet but did little to hinder the raid. The intense battle would be set to rage on throughout the night and continue into the following day until, sensing victory was in their hands, the English eventually withdrew, having destroyed a large proportion of the Spanish ships, estimated at around twenty-five vessels, give or take. The ships were looted, burnt or sunk. Drake’s job was done.

Drake continued his plunders after the successful attack on the port of Cádiz. The Iberian coastline was not safe from the English pirate, as he continued elsewhere destroying ships and looting supplies and provisions. The raid became known as the “singeing the King of Spain’s beard”, a phrase coined by Drake himself. The strategic value of his actions could not be underestimated. For a whole year the Spanish Armada was delayed, giving precious time to England to make defensive decisions and preparations.

The naval expedition was a resounding success. Spain’s economic power was dented, and the political jostling for power lay firmly in English hands, after such an audacious act carried out on Spain’s own doorstep. Drake had made a success of the Queen’s mission and boasted that he had “singed the King of Spain’s beard”.

Nevertheless, everyone, including Drake himself was aware that it was only a matter of time before the two great naval powers of England and Spain would come together in an explosive naval battle where only one could reign supreme. In the meantime, Drake would bask in his glory. In 1581 Drake was awarded a knighthood by Elizabeth I and Sir Francis Drake would soon assume the role of Vice Admiral against the Spanish Armada and witness the English victory in 1588.

Drake’s expedition into the port of Cádiz in April 1578 proved to be a pivotal turning point in the sixteenth century power struggle between Spain and England. Drake’s pre-emptive strike sunned the Spanish and bought England precious time to prepare for an invasion. Drake’s naval adventures awarded him cult status in England as a naval hero. He died of dysentery in January 1596 leaving behind an extensive maritime legacy.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.