Sir Walter Scott was born on 15 August 1771, in a small third floor flat in College Wynd in Edinburgh’s Old Town. Scott was the ninth child of Anne Rutherford and Walter Scott, a solicitor and member of the private Scottish society known as the Writers of the Signet, so called for their entitlement to use the Scottish King’s seal – known as the signet – when drawing up legal documents.

Whilst the Scott’s home near the University was a popular area for lecturers and professionals like Scott’s father to live, in reality the small, overcrowded alleyway saw little natural light and clean air and suffered from a lack of proper sanitation. Unsurprisingly perhaps then, that six of Anne and Walter’s children died in infancy and the young Walter (or ‘Wattie’ as he was affectionately known) contracted polio as a toddler. Despite early treatment his right leg remained lame for the rest of his life.

In 1773, Walter was sent to live with his grandparents on their farm at Sandyknowe, in the border area of Roxburghshire, 30 miles from Edinburgh. It was hoped that some time spent in the countryside would improve Scott’s ailing health and indeed it did. This time spent with his grandparents and attentive Aunt Janet (or ‘Jenny’ as she was more commonly known) meant that he was sufficiently strong enough to return to Edinburgh and start school in January 1775, following the death of his grandfather Robert Scott. During his time at Sandyknowe Jenny encouraged Scott’s literary pursuits, reciting poetry to him when he was too ill to leave his bed and teaching him how to read. His grandmother Barbara would also keep the young boy amused with stories of their ancestors and the border battles between the Scots and the English. It was then that Walter developed his enduring appreciation of ballads and his keen interest in the Scottish heritage. On his return to Edinburgh – to his family’s large new home at 25 George Square in the New Town area of the city – Scott was able to thoroughly explore the city with the aid of a cane.

Having been privately educated on his return, Scott then attended the Royal High School of Edinburgh in October 1779. As the high school did not focus on arithmetic or writing, Walter also undertook further tuition from the staunch patriot James Mitchell, who also threw in some teachings of the Scottish Church and the Scottish Presbyterian movement for good measure.

In his last year at the high school Scott had grown several inches, and fearful that he would no longer have the strength to carry his larger frame, he was once more sent to stay with his Aunt Jenny in 1783, this time at the small border town of Kelso where she was now living. During his six months at Kelso, Walter also attended Kelso Grammar School and it was here that he made one of the enduring friendships of his life, with future business partner and publisher James Ballantyne, who shared Scott’s love of literature.

Already an avid reader of epic romances, poetry, history and travel books, Walter returned to Edinburgh to study classics at the University from November 1783. In March 1786 Walter began an apprenticeship at his father’s office with the intention to become a Writer to the Signet, however it was decided that he would aim for the Bar and so he returned to the university to study law. It was at this time that Scott met the other great Scottish Poet, Robert Burns, at a literary salon in the winter of 1786–87. It was said to be the only meeting between the pair, and the 15-year old Scott ingratiated himself to the older Burns by being the only one present to identify the author of an illustrated poem Burns had happened upon (the poem being “The Justice of the Peace” by the English translator, poet and priest John Langhorne).

Having qualified as a lawyer in 1792, Walter received a modest income as an Advocate whilst he spent the next few years foraying into literature by translating noted German works into English for publication by his friend Ballantyne.

In September 1797 on a visit to the Lake District, Scott met Charlotte Carpentier. Following a whirlwind courtship, Scott proposed to Charlotte only three weeks after their initial meeting, much to the disproval of his parents. Charlotte’s French origins led them to believe she might be Catholic and they insisted on learning more about her family. Their concerns were allayed when they discovered she was a British citizen and had been christened in the Church of England. The fact that she was financially comfortable was another plus! The couple were married on Christmas Eve 1797 at St Mary’s Church in Carlisle, returning to live in Edinburgh the same night. It was a happy union, broken only by Charlotte’s death thirty years later on 15th May 1826.

In 1809, Scott joined James Ballantyne and his brother as an anonymous silent partner in their publishing house, John Ballantyne & Co. Many of Scotts subsequent poems were published by the company, including the well known The Lady of the Lake, whose German translation was set to music by the composer Franz Schubert. Scott’s 1808 poem Marmion, about the battle between the English and Scottish at Flodden Field in 1513 introduced his most oft’ quoted rhyme, which is still regularly used today:

Oh! what a tangled web we weave

When first we practise to deceive!

Scott’s popularity as a poet was cemented in 1813 when he was given the opportunity to become Poet Laureate. However, he declined and Robert Southey accepted the position instead.

The Novels

In 1814, when the publishing house suffered the first of two significant financial blows, Scott began writing novels as a means of bettering his fiscal situation. That same year his first novel, Waverley, was published anonymously and its worldwide success prompted further volumes in the Waverley series, each with a Scottish historical setting.

Whilst many eventually came to suspect Scott as the author, he continued to produce these and other novels under a pseudonym until officially admitting he was the author in 1827. What had begun as an attempt to uphold his reputation as a serious poet and Clerk of the Court Session should this more whimsical genre have been unsuccessful, also enabled Scott to indulge his passion for the romance and mystery about which he wrote.

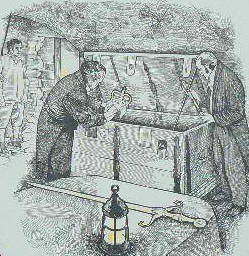

(above) The ‘discovery’ of the Honours of Scotland by Sir Walter Scott in 1818

The Prince Regent (later George IV) was so impressed by Scott’s work that In 1818 he gave him permission to search Edinburgh Castle for the Royal Scottish regalia. The searchers eventually found them in the little strong room at Edinburgh Castle locked in an oak chest, covered with linen cloths, exactly as they had been left after the Union on 7th March 1707. They were put on display on February 4th, 1818 and have been on view ever since in Edinburgh Castle, where thousands come to see them each year.

Having been granted the title of baronet in 1820, Sir Walter Scott was heavily involved in arranging King George IV’s visit to Scotland in 1822 (the first Scottish visit by a ruler of the Hanoverian dynasty), and the ceremonial tartans and kilts Scott had displayed throughout the city during the visit brought the garments back into contemporary fashion and cemented them as important symbols of the Scottish culture.

In 1825 the publishing house faced further financial difficulties resulting in its near closure. These difficulties were brought about in part by Scott’s attempts to finance his Abbotsford Estate and other landholdings but also the shift to more cautious trading in the city of London at the time.

Scott chose not to declare himself bankrupt, but instead he entrusted his estate and assets to his creditors and produced a prolific amount of literature over the next seven years as a means of wiping out his debt. Having suffered a stroke in 1831, which resulted in apoplectic paralysis, his health continued to fail and Scott died on 21st September 1832 at Abbotsford.

He was buried alongside his wife Charlotte at Dryburgh Abbey in the border town of Melrose. At the time of his death Scott was still in debt, but the continued success of his writings meant that his estate was eventually restored to his family.

Scott today

Having been one of the first English-language authors to succeed international in his own lifetime, Scott’s works are still widely read today with many such as Ivanhoe, and Rob Roy being adapted for the screen.

However, whilst Scott was one of the most popular writers in both Britain and the United States in the nineteenth century he was not without his detractors. The American author Mark Twain was definitely not a fan, ridiculing Scott by naming the sinking boat after the Scottish writer in his famous 1884 novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Following the Modernist movement in literature in the aftermath of the first World War, Scott’s rambling and verbose text (indeed he was alleged to omit punctuation in his writing, preferring to leave this to the printers to insert as required) was no longer in vogue.

Nevertheless, Scott’s impact on both Scottish and English literature cannot be denied. He created the modern historical novel which has inspired generations of writers and audiences alike and his input to the Highland revival put Scotland back on the map. Whilst perhaps not as immediately synonymous with Scotland as his predecessor Burns, Scott has been immortalised in monuments as far apart as Glasgow and New York and still appears on the front of Scottish bank notes. His famous creation – the Waverley novels – is also commemorated via Edinburgh’s famous Waverley rail station.