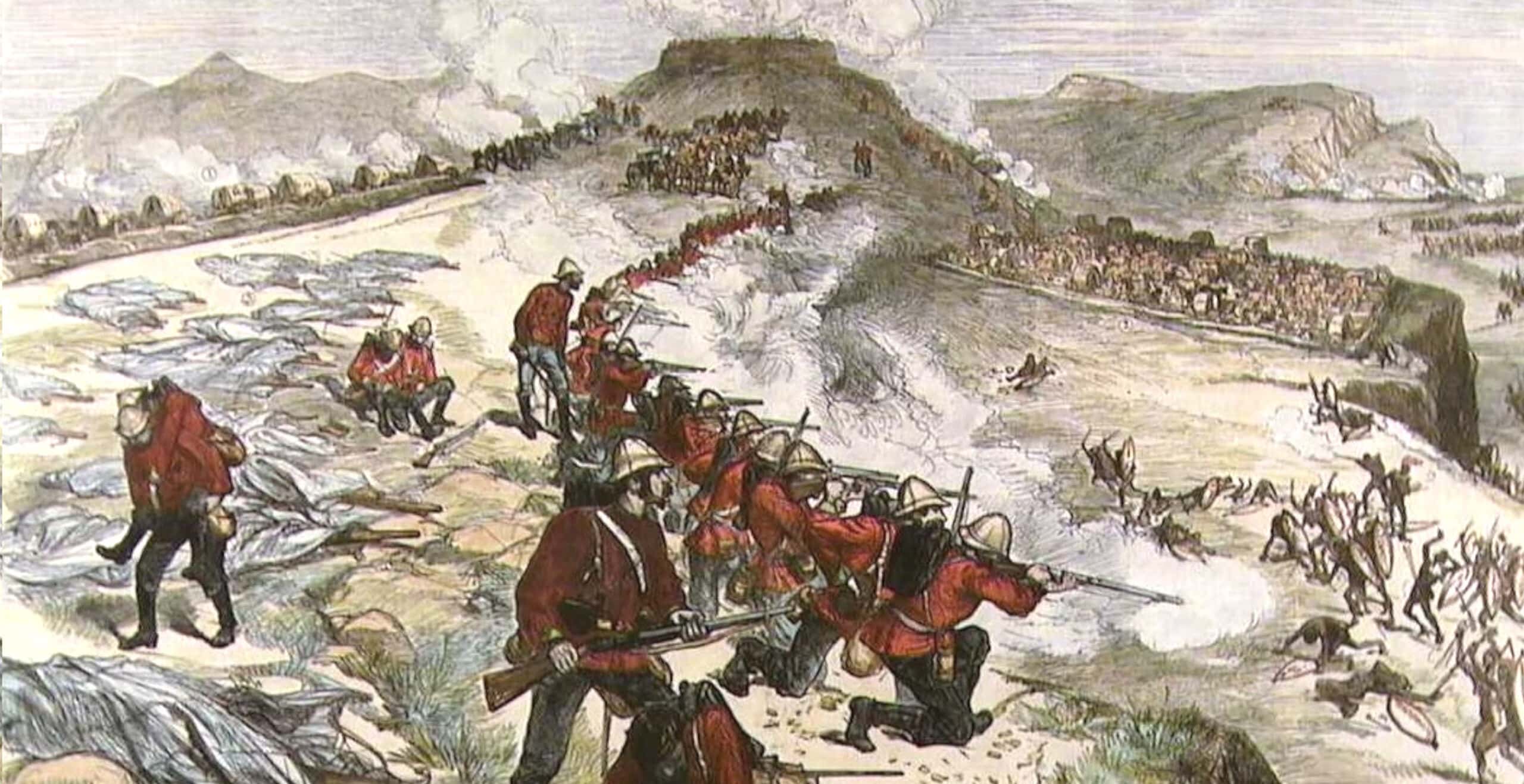

FOUR weeks before Lord Chelmsford’s invading force ended the Anglo-Zulu War by defeating King Cetewayo’s army at the Battle of Ulundi, a Zulu impi killed Louis Napoleon, the heir to the French throne.

The Prince Imperial’s death on 1 June 1879 ended the Napoleonic dynasty and dashed French royalists’ hopes of restoring the monarchy to republican France.

Lt. Jahleel Brenton Carey (32), the Prince’s French-speaking companion in a scouting party, became the scapegoat for the tragedy, but the real culprits were the Empress Eugenie of France and her friend, Queen Victoria, who sent Louis to South Africa.

Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli was exasperated by their decision because he foresaw the dreadful repercussions if the Prince died in action whilst serving as a British officer. He complained to a friend: “I tried to stop him going, but what can you do when you have two obstinate women to deal with?”

Louis (22), only child of Charles-Louis Napoleon III and his Spanish wife Eugenie, was gone within two days and on 31 March 1879 disembarked from a sailing ship in Durban to meet his fate.

When the republicans seized power after Napoleon III’s defeat in the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, Empress Eugenie and Louis (14) were hurried off to England where they were befriended by Queen Victoria and settled in Camden Place estate at Chislehurst. The Emperor joined them six months later when the Prussians released him from captivity, and the three settled down to a life in exile.

Louis was dressed in a uniform as a child, tutored in the duties of an emperor and was encouraged to follow a military career. He attended the Royal Military Academy at Woolwich and was there in 1873 when his 64-year-old father died after surgery for bladder stones. In the eyes of royalists he was effectively Emperor Napoleon IV when he graduated from Woolwich seventh in a class of 34, scoring a first in riding and fencing.

He lived in a state of boredom until news of the Isandlwana disaster reached England and he pleaded with his mother to be allowed to join Chelmsford’s army.

Disraeli knew that royalists hoped to restore the Napoleonic dynasty to France but they did not want Louis to become a British army officer. The solution was to make him “a private spectator” dressed in a plain uniform without insignia so that he could experience the life of a soldier and satisfy his thirst for adventure.

On his arrival in Durban, General Lord Chelmsford assigned Louis and Lt. Carey to assist Quartermaster-General Colonel Richard Harrison to scout a route for the second British invasion of Zululand.

They joined the 200-strong cavalry of Colonel Redvers Buller on May 13 and the next day Louis finally found himself in enemy territory. Wearing the sword of his great uncle, Napoleon Bonaparte, the Prince was so excited that when he saw Zulus in the distance he broke ranks and chased them on Percy, the skittish grey horse he’d purchased in Durban. He was anxious to test his sword against Zulu assegais but was restrained by an annoyed Col. Buller.

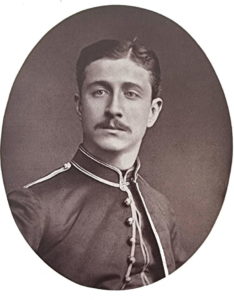

The Prince Imperial in 1879

The Prince Imperial in 1879

When Buller complained to Chelmsford about the Prince’s irresponsible behaviour the commander-in-chief ordered the headstrong young man not to leave camp without a strong escort. While Louis was on patrol a few days later he again chased a lone Zulu and was ordered to return immediately. As he pulled up and slammed his sword into its scabbard, he groused: “Am I never to be without a nurse?”

On the evening of May 31, the Prince asked Col. Harrison if he could join a reconnaissance party the next day. Harrison agreed, providing he had an escort of six Bettington’s Horse troopers and six riders of the Edendale contingent. Later, Lt. Carey poked his head into Harrison’s tent and requested permission to accompany the patrol in order to verify sketches he had made on a previous scouting mission, Harrison again agreed but did not indicate who was to be in command of the party.

At 9 a.m. on June 1, six riders of Bettington’s Horse reported for escort duty. Senior among them was Corporal Grubb with Troopers Rogers, Cochrane, Willis, Abel and Le Tocq (a French-speaking Channel Islander), and a Zulu guide. When the six troopers of the Edendale contingent failed to appear, Harrison assured Carey that they would be sent after him and, in the meantime, the Prince’s party could call on other mounted troops scouting along the line of advance.

Louis was riding the fractious Percy and, like Carey, was armed only with a revolver and a sword attached to his saddle, while the troopers carried Martini Henry carbines.

When the six Edendale troopers sent cantering after them by the cavalry brigade-major did not arrive, Carey should have insisted on finding another escort group, but he and Louis did not bother to do so.

The Prince’s party rode towards the valley of the Ityotyosi River until, at 12-30 p.m., Louis gave the order to off-saddle. Then, seeing what he thought was a deserted kraal in the distance, he told Carey: “Let’s go down to the huts by the river and the men can get wood and water.”

Lt. Carey objected to the suggestion because the troopers would be unable to keep the surrounding countryside under observation, but as Louis made his wishes known “in a very authoritative manner,” Carey allowed himself to be overruled. Upon reaching the kraal the Zulu guide warned that it had been recently occupied. Carey and Louis, however, did not respond and, ignoring common-sense military precautions, failed to post sentries or investigate the head-high grass surrounding them.

Their horses were off-saddled and knee-haltered, again on the Prince’s orders, and a fire was lit to brew coffee. Carey and Louis were soon busily engaged with their maps and sketches while the troopers sprawled at ease.

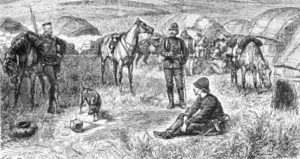

This sketch of the Prince’s party resting at the kraal appeared in “The Graphic” of September 1879. The Zulu guide and Louis’s terrier, Nero, are on the left, Lt. Carey in the middle and Louis (seated) in the foreground. The dog was also killed and mutilated by the Zulus.

This sketch of the Prince’s party resting at the kraal appeared in “The Graphic” of September 1879. The Zulu guide and Louis’s terrier, Nero, are on the left, Lt. Carey in the middle and Louis (seated) in the foreground. The dog was also killed and mutilated by the Zulus.

At 3-30 p.m. Carey suggested that they should saddle up and move on, but he again deferred to Louis when he insisted on remaining for another 10 minutes. Four minutes later the guide shouted that he had seen armed Zulus nearby, so they all collected their mounts and prepared to saddle-up. Carey was in the saddle first but Louis delayed them by going through the formal routine of mounting his men.

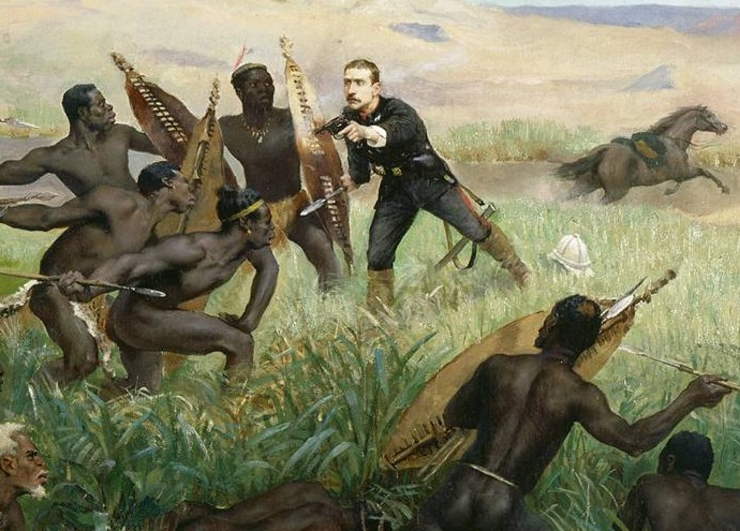

“Prepare to mount,” he ordered, and as the troopers placed their left feet in the near stirrup a tremendous volley crashed out from the tall grass and about 40 Zulus charged out shouting their war-cry “uSuthu!”

Believing that the others were close behind him, Carey put spurs to his horse. Rogers was slow to mount and when the Zulus pulled him down he managed to fire one shot with his carbine before he was killed.

A bullet whistled past Grubb’s ear as he galloped away and smacked into Trooper Abel’s back, causing him to fall off his horse. Abel and the Zulu guide were then rapidly surrounded and stabbed to death.

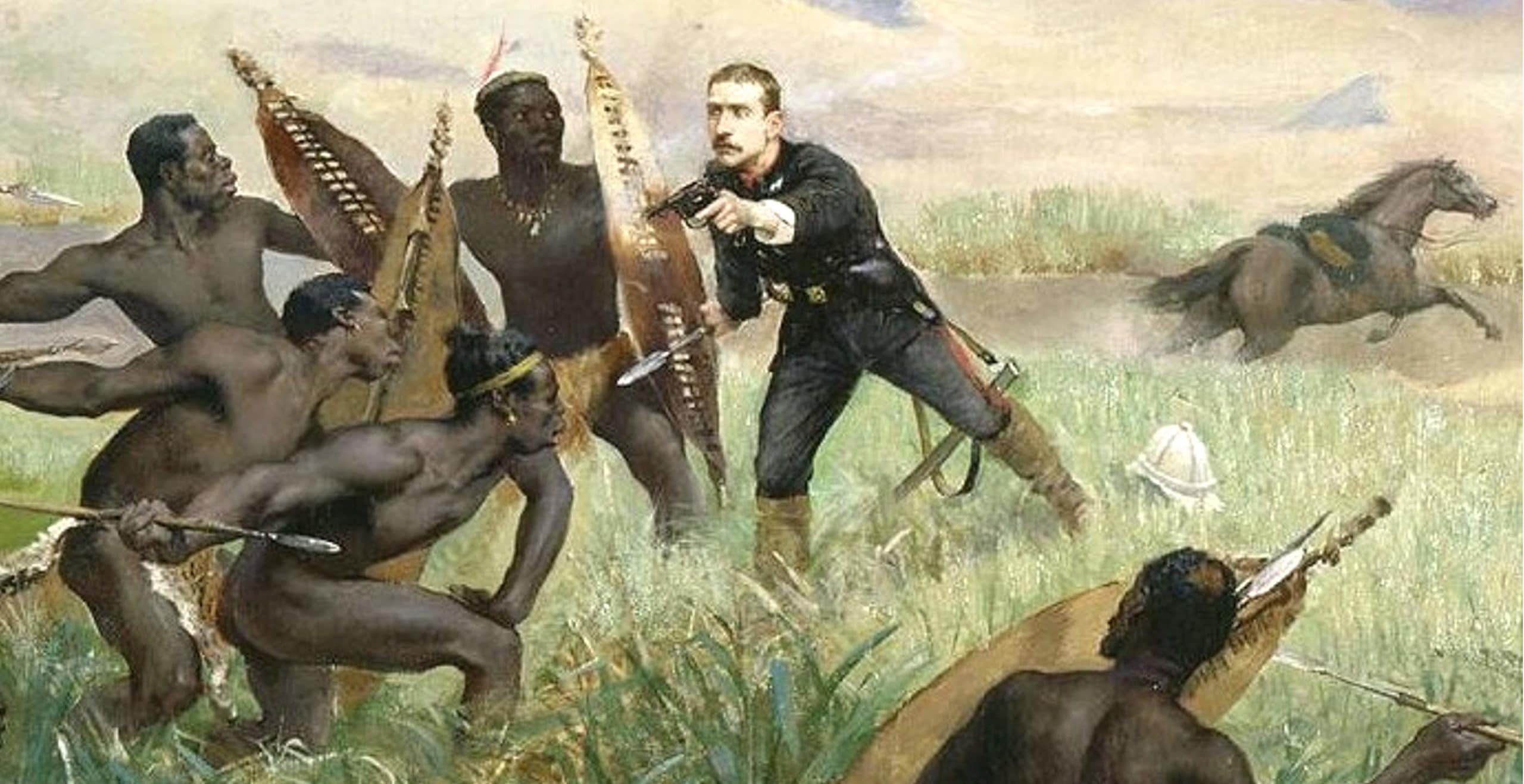

The Prince also failed to mount. Percy panicked when the shots were fired and dashed off with Louis clinging to the saddle holster. For more than 100 yards he clung to the holster and tried to vault into the saddle – until the faulty leather strap holding it tore away and he fell under the racing horse, injuring his right arm.

Six Zulus were quickly upon Louis, who held his revolver in his uninjured left hand and fired twice before the Zulus closed in and an assegai thudded into his thigh. He pulled it out and rushed at his attackers, fighting desperately until he sank into a sitting position, exhausted by loss of blood. There was a brief hacking flurry, and then it was all over. Disraeli’s worst fears had been realised.

As the survivors reined-in their mounts out of gunshot range and looked back, Lt. Carey’s face revealed his dilemma. Should he save the lives of his five remaining men or return to the kraal to verify that four others were dead? The rapid approach of the pursuing Zulus convinced him that he should head back to camp at Itelezi Hill and face the consequences.

Lord Chelmsford turned white with shock when he was informed of the tragedy. Col. Buller did not mince his words and told Carey he deserved to be shot.

Chelmsford declined to send out a rescue force until next morning when the 17th Lancers and colonial horsemen were paraded at 5 a.m. They totalled more than 1,000 men, a vast contrast to Louis’ small escort the previous day.

Trooper Abel’s mutilated naked body was the first one found. The stomachs of Trooper Rogers and the Prince had also been ritually slashed open. Louis’s body was naked except for a gold chain with a medal of the Virgin Mary and his great-uncle’s seal twisted about his neck. One assegai had stabbed him in the heart and another had cut his brow and pierced his right eye to the brain. Seventeen assegai wounds suggested that he fought desperately until the end.

The body was carried to the camp and then to Pietermaritzburg, where it lay in state in St. Mary’s Catholic Church before being loaded onto a British warship in Durban and taken to England for an impressive funeral in Chislehurst attended by 40 000 people, including Queen Victoria. The Empress Eugenie was too distraught to appear.

Back in South Africa, the anger within the Field Force against Lt. Carey was intense. At his court-martial on June 12 he pleaded not guilty to a charge of “misbehaviour in the face of the enemy” and said he had joined the reconnaissance group to check the accuracy of his route sketches. He argued that Col. Harrison had not appointed him to take charge and had emphasised that he “should not interfere with the Prince.”

Carey was nevertheless found guilty, but when the court-martial’s proceedings were published on August 16 the Adjutant-General stated that the case against him was not proven. Lt. Carey was promoted to captain and later sent to re-join his regiment in India, where he was shunned by his fellow officers until he died from peritonitis in 1885.

Queen Victoria sponsored Empress Eugenie’s 1880 pilgrimage to Natal ao that she could spend the night in vigil on the first anniversary of Louis’ death, and a cross donated by the Queen was erected at the site of the tragedy 70 km from Dundee.

Eugenie died in 1920 at the age of 94 and her remains were interred alongside her husband and son in the Imperial Crypt at St. Michael’s Abbey, Farnborough, which became a place of pilgrimage for French royalists.

In South Africa, the Prince’s death is commemorated annually in June with the many attractions of French Week, including a guided tour to the Prince Imperial Monument on the KwaZulu-Natal Battlefields Route.

English-born Richard Rhys Jones is a veteran South African journalist specialising in history and battlefields. He was Night Editor of South Africa’s oldest daily newspaper “The Natal Witness” before going into tourism development and destination marketing. His historic novel “Make the Angels Weep” covers life during the apartheid years and the first stirrings of black resistance. Published in 2017, it is available as an e-book from Amazon Kindle.

Published: 27th May 2022.