British political life in the latter half of the nineteenth century was dominated by two very diverse characters: William Ewart Gladstone (1809 – 1898) and Benjamin Disraeli (1804 – 1881). During their long political careers, each served as Chancellor of the Exchequer and Prime Minister.

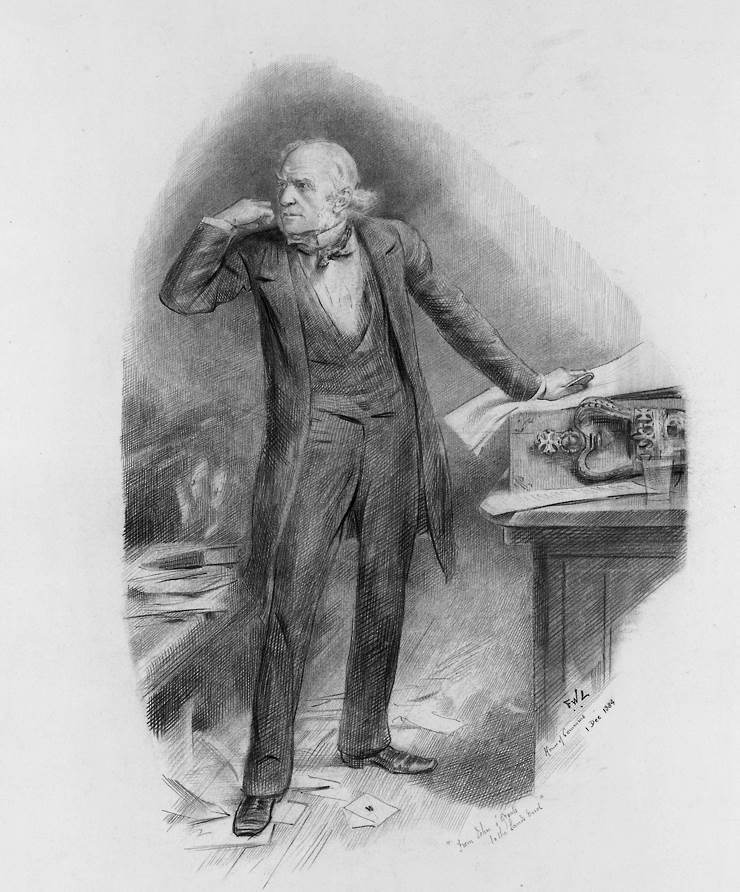

Gladstone’s enduring time in politics earned him the title of Grand Old Man, abbreviated to G.O.M., although cynical rivals claimed the initials stood for “God’s Only Mistake”. Witty Disraeli has been credited with coming up with this version. Whoever coined it, it’s a good indication of the vitriolic rivalry between the two.

Disraeli is also credited with saying “If Gladstone fell into the Thames, that would be misfortune; and if anybody pulled him out, that, I suppose, would be a calamity”. He certainly called Gladstone an “unprincipled maniac”, and said he was “an extraordinary mixture of envy, vindictiveness, hypocrisy and superstition”. Gladstone’s response is apparently unrecorded, and perhaps that’s just as well.

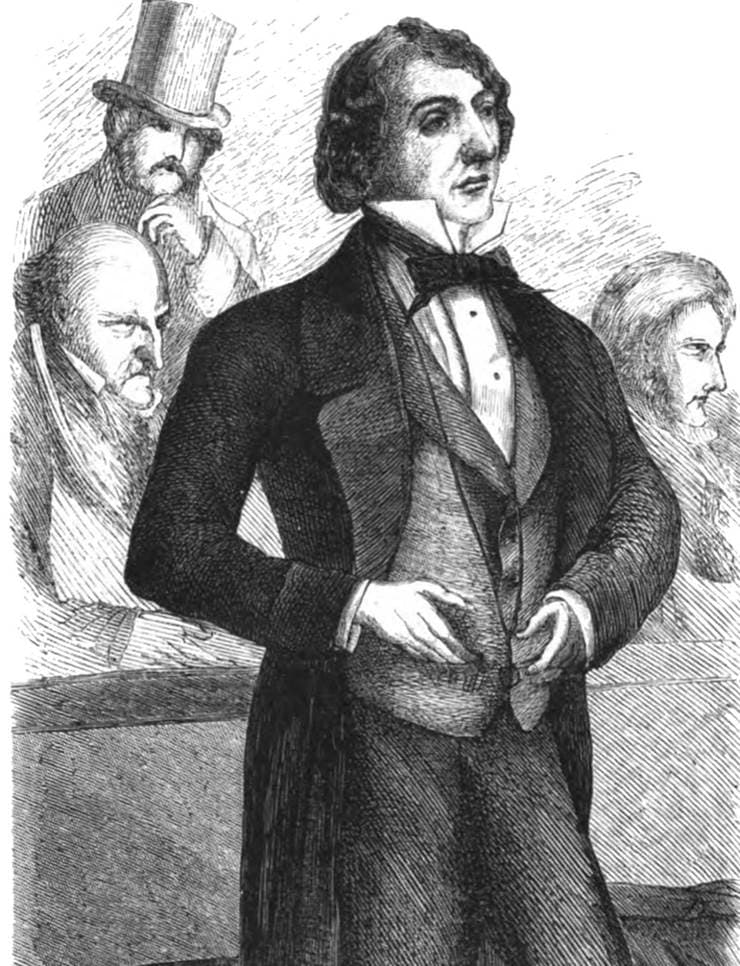

Disraeli’s Jewish father, Isaac D’Israeli, had joined the Church of England in 1813, when Benjamin was still a child, and Benjamin Disraeli was baptised as a Christian in 1817. His family was a well-educated and literary one. Ambitious Disraeli brought flair and oratory to British politics.

William Ewart Gladstone was born in Liverpool of Scottish parents, and his wife was Welsh. His constituency was in Scotland. With this combined social and political background, Professor H.C.G. Matthew of Oxford University describes him as becoming “that very rare phenomenon, a fully ‘British’ politician”, in the sense his connections extended all over the island of Britain.

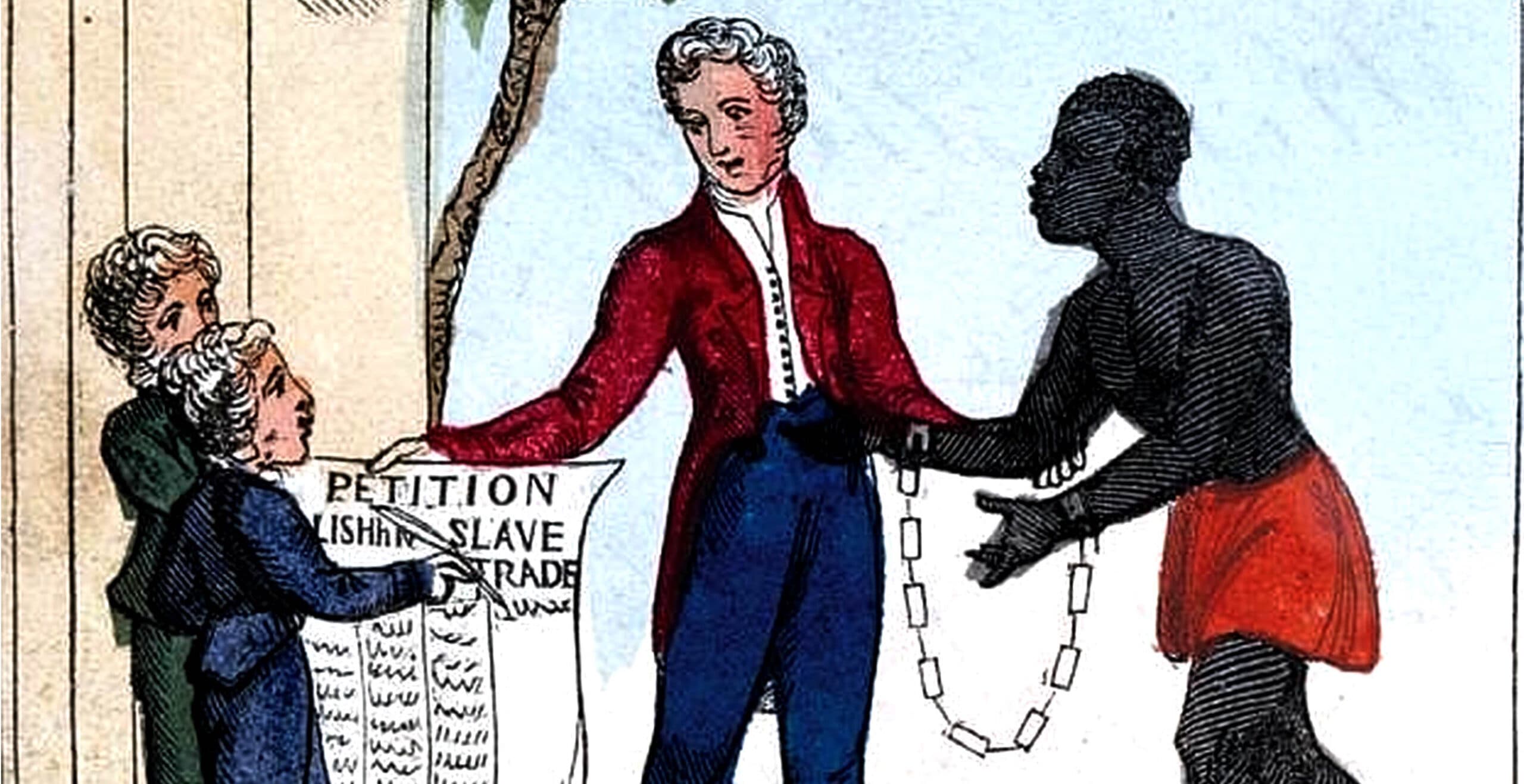

There was more to the Gladstone family than this. Gladstone’s father John owned slaves and his plantations were the source of most of the family’s wealth. John Gladstone’s Demerara plantation, known as “Success”, was the focus of the outbreak of the Demerara rebellion of 1823, which revealed the horrific conditions of the enslaved people on the plantations to the wider public. This ultimately resulted in the Abolition of Slavery in the British Colonies Act of 1833.

The family wealth meant that William Gladstone’s education took the standard course of the comfortably-off: preparatory school, Eton, and Christ Church College Oxford. Disraeli, on the other hand, much regretted that his parents had not sent him to Winchester College like his brothers, and found his partly private, partly minor school education inadequate. He struggled with various careers and activities in his early years, turning to writing to clear his debts, and falling in and out of friendship with publishers and several kinds of radical politics along the way. Sponsorship by the Tory politician Lord Lyndhurst sealed his political fate as a conservative.

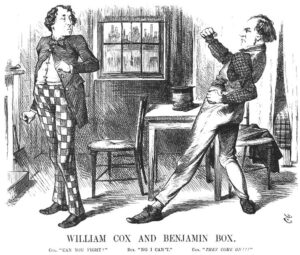

It’s tempting to portray the subsequent relationship between the two politicians as the ultimate match between political rivals, like the thus far mythical cage-fight between Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg. “Inna yellah cor-nah for the Liberals! My lords, ladies, and gentlemen, the-ah Grand-ah Old-ah Maan! I give you the People’s William, Mistah W. E. Gladstone! And inna blue cor-nah for the Conservatives, the 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, Queen Vicky’s favourite, Mistah Benjamin Disraeli!”

Jim Dixon, the protagonist of Kingsley Amis’s novel Lucky Jim, divided the world into two groups: people he liked, and people he didn’t. Queen Victoria might have appreciated these categories, although she probably wouldn’t have approved of Jim’s wild, drunken behaviour. In much the same way as Dixon, Victoria divided her prime ministers up into those she liked, and those she didn’t. After a wobbly start, Disraeli was firmly ensconced in the former group, and Gladstone categorically in the latter.

“He speaks to me as if I were a public meeting!” sniffed Queen Victoria disapprovingly, most unamused by Mr Gladstone’s manner.

“When I want to read a novel – I write one,” said droll Mr Disraeli, angling for a place in the “Great Wits of the Nineteenth Century” club. It’s unlikely that Queen Victoria greeted his bon mot with a dig in the ribs and a shriek of “Ooh, Mr Disraeli, you are a card!” but she may have allowed herself an amused smile.

After an initial chill in the relationship due to Disraeli’s treatment of Prime Minister Robert Peel, In Victoria’s eyes delightful Mr Disraeli could do no wrong. After all, he was an enthusiastic supporter of the British imperial project, and did he not make her Empress of India with his act of 1876?

As for Gladstone…that annoying old bore with his booming voice and his habit of churning out dull pamphlets on politics and the classics and religion…not to mention that really quite unusual obsession with “rescuing” fallen women… Privately, Disraeli told Matthew Arnold that “Everybody likes flattery; and, when you come to royalty, you should lay it on with a trowel”. It certainly didn’t do any harm in his relationship with Victoria.

And so, the stage was set for a clash of political cultures and personalities. The antagonism began in earnest when Gladstone was still a member of the Conservatives, and gained office under his mentor Sir Robert Peel (1788-1850) in 1841. Disraeli, having shown great commitment and potential to the party, was overlooked, and although he continued to support Peel for several years, ultimately he would oppose him. This would lead to a major schism in the Tory party, and accusations from Gladstone and other members that “Dizzy” was responsible for its destruction.

Given the dominance of Gladstone and Disraeli in nineteenth century politics, and the focus on their personalities, it’s all too easy to forget that these were politicians whose decisions were literally matters of life and death for populations across the world. One such concern was the repeal of the Corn Laws, a divisive issue for the Conservatives. The Corn Laws were instituted in 1815 as a means of protecting Britain’s landowners by setting high tariffs on imported grain, so that the British producers could control production and distribution of British cereals, and maintain their profits.

In 1845, the arrival of the first of several devastating blights destroyed most of Ireland’s staple, the potato crop. Within a very short space of time, people in Ireland were starving and desperate. Prime Minister Peel took what is viewed as a principled stand, and a courageous one given his reliance on support from the Tory landowners, to repeal the Corn Laws in order to make cheaper food available for Ireland. In this he was opposed by Disraeli, Lord George Bentinck, and the landowners.

Disraeli had argued for understanding between the British working class and the landed class, and believed that an enfranchised working-class would naturally vote for its existing rulers, whom he said he also was naturally drawn to support. However, the Great Famine in Ireland, which would today be viewed for what it was – a humanitarian crisis – became embroiled in the political game. Absentee landlords exacerbated the situation by continuing to demand – and obtain – their rents, so that the crops raised in Ireland by their tenants were sold to Britain in order to pay their debts. The crisis deepened, and people starved to death.

The outcome of this was not only a lasting division in the Tories between Peelites and Protectionists, but also a lasting antagonism between Gladstone and Disraeli on numerous issues, from Irish Home Rule to Disraeli’s imperial policies. After Gladstone joined the Liberal party and became its leader, they fought over conflict in the Balkans and the issue of the Suez Canal, over maintaining peace in Europe at all costs and over attitudes to ritual in religion. Gladstone’s awkward character and tendency to preach couldn’t match Disraeli’s eloquent discourse. Disraeli’s literally dizzy attitude to finances couldn’t match Gladstone’s undoubted head for figures and governmental fiscal management.

Was the Gladstone-Disraeli “feud” really so intense, or was at least some of it overemphasised or even manufactured? They were perhaps not so politically, or even personally divergent as history has suggested. Both had politically conservative roots but were capable of support for both radical and conservative causes. Both had been intended for careers in the law. Both were committed to the established Protestant Church and Gladstone had considered a career in the Church at one point. Both were prolific writers who depended on their very different ways with words for their incomes at various times.

Historians of the period recognise them equally as great personalities of the Victorian age, despite their differences and inevitable errors of political judgement. And perhaps both would have agreed that the authority, influence, and historic legacy of two such different characters emphasises the important role of diversity in British politics. Churchill argued that the rivalry between Gladstone and Disraeli transformed British politics and led to reform. However, it might equally be argued that the personal animosity between the two overrode more measured judgement when it came to making decisions either for the good of the country or the wider world.

There’s an irony in Gladstone, the man from the wealthy, privileged background becoming known as a people’s champion. There’s an equal irony in Disraeli, the political outsider who would not have been able to take office due to being Jewish had his family not converted, becoming the ultimate upholder of traditional British monarchy and imperial ambition. Both were ultimately consummate career politicians.

In retrospect, it is also interesting that Liberal party Prime Minister William Gladstone’s legacy is much more controversial than that of Disraeli, the unlikely political outsider and Conservative. In 2023, the descendants of John Gladstone, William’s father, made a public apology for their ancestor’s involvement in enslaving African people. Although opposed to slavery later in life, William Gladstone did not support abolition earlier in his career, and helped to ensure that his father was compensated with £106,000 on the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, the equivalent of £11,000,000 In 2023.

Gladstone later fell out with his father over the issue of slavery and took action to bring the slavery that continued in the Americas to an end. He admitted late in life that this was one of the issues on which the anti-slavery majority had been in the right and the ruling classes wrong.

A further Gladstone controversy arose in 1927, when Wright versus Gladstone hit the headlines. A journalist, Peter Wright, published a book of essays in which he described Gladstone as having founded “a great tradition since observed by many of his followers and successors with such pious fidelity, in public to speak the language of the highest and strictest principle, and in private to pursue and possess every sort of woman”. This was a not very subtle comment on Gladstone’s famous tendency to rescue women from the streets.

Gladstone’s surviving sons Viscount Gladstone and his brother Henry, both in their 70s at the time, took legal advice and ultimately action against Peter Wright. Although technically it is not possible to take legal action for libel against a dead person, the Gladstone brothers, by employing one of the nation’s leading barristers (and committed Liberal) Norman Birkett, achieved a remarkable outcome. To support the brothers’ case that William Gladstone’s memory and reputation had been unjustifiably damaged, even Lily Langtry was sufficiently incensed to send a telegram from her retirement in Monte Carlo: “Strongly repudiate slanderous accusations by Peter Wright”.

The jury concluded that Wright had done wrong, and William Gladstone’s moral reputation remained untarnished. Norman Birkett counted this one of his most successful cases. Peter Wright apologised, and the case ended amicably enough. Perhaps the courtesan Catherine Walters, better known as Skittles, might have had a word or two to say had she still been alive, since Gladstone had been in the habit of regularly taking tea with her. However, Skittles was known for her discretion.

Finally, it is worth pointing out that both politicians ultimately benefitted from the fact that their careers were built, like those of late twentieth century politicians, in the reign of a resolute, long-lived monarch. The popularity of Queen Victoria, like Queen Elizabeth II, ultimately outlasted those of the politicians. After all, during her reign Victoria saw nine Prime Ministers come and go, and Elizabeth no fewer than sixteen!

By Dr Miriam Bibby. Dr Miriam Bibby is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 31st August 2023.