On 28th August 1833 a very important act received its Royal Assent. The Slavery Abolition Law would finally be enacted, after years of campaigning, suffering and injustice. This act was a crucial step in a much wider and ongoing process designed to bring an end to the slave trade.

Only a few decades previously, in 1807 another act had been passed which had made it illegal to purchase slaves directly from the African continent. Nevertheless, the practice of slavery remained widespread and legal in the British Caribbean.

The fight to end the slave trade was a long drawn out battle which brought to the surface a host of issues ranging from politics and economics to more social and cultural concerns.

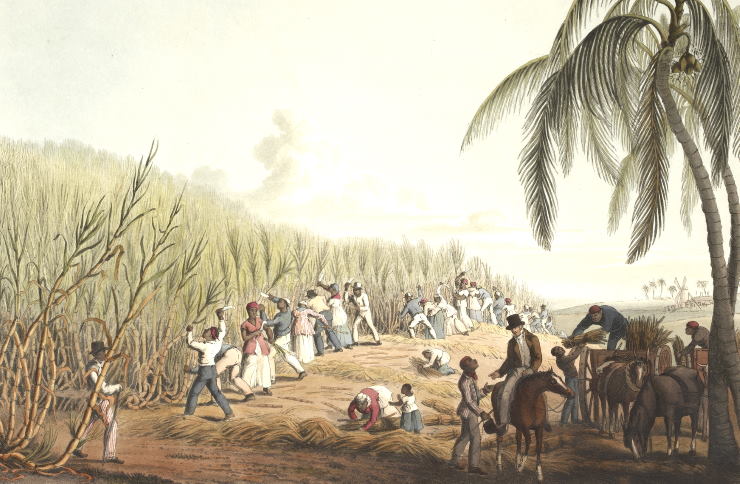

The decision to bring the practice of slavery to an end was a contentious one. Britain had been engaged in slavery since the sixteenth century, with economic prosperity being secured through the use of slave-grown products such as sugar and cotton. The British Empire relied on cultivating products in order to trade in a global market: the use of slaves was paramount to this process.

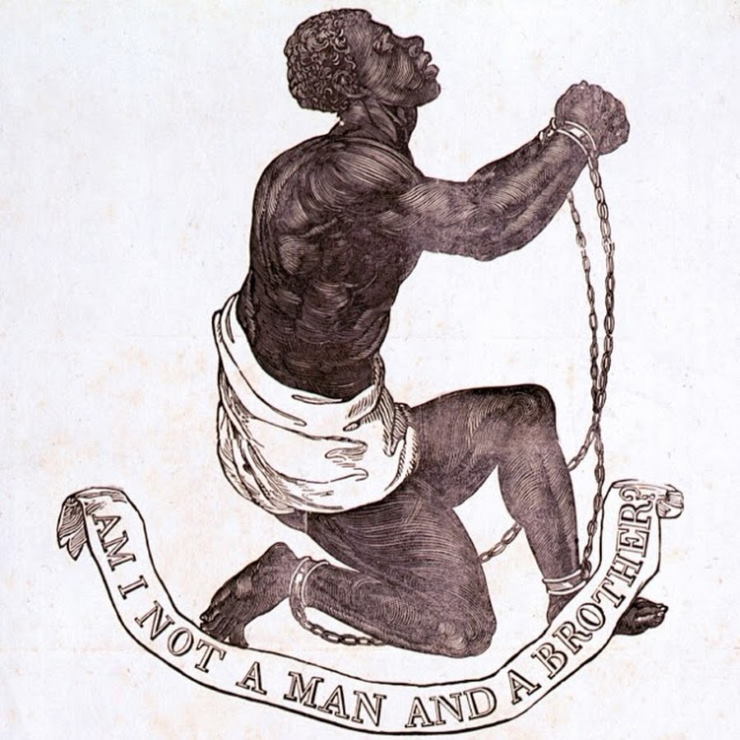

By the late 1700’s, times were changing, social norms were challenged and the stage for revolution in Europe was set. Concerns over equality, humanity and the rights of man gave way to individuals championing the cause of abolishing the antiquated and barbaric practice of slavery.

The campaign in Britain was led by significant Quaker anti-slavery groups who made public their concerns and brought it to the attention of politicians who were in a position to enact real change.

In May 1772 a significant court judgement by Lord Mansfield in the case of James Somerset, who was an enslaved African, versus Charles Stewart, a Customs Officer. In this case, the slave who had been purchased in Boston and then transported with Stewart to England had managed to escape. Unfortunately, he was later recaptured and subsequently imprisoned on a ship bound for Jamaica.

Somerset’s cause was taken up by three godparents, John Marlow, Thomas Walkin and Elizabeth Cade who made an application to the courts to determine whether there was a legitimate reason for his detention.

In May, Lord Mansfield gave his verdict ruling that slaves could not be transported from England against their will. The case therefore gave great impetus to those campaigners such as Granville Sharp who saw the ruling as an example for why slavery would be unsupported by English law.

Nevertheless, the ruling did not advocate abolition of slavery completely. Those backing Somerset argued that colonial laws which permitted slavery were not in conjunction with the common law of Parliament, thus making the practice unlawful. The case in question was still argued very much along legal lines rather than humanitarian or social concerns, however it would mark an important step in a trajectory of events which ultimately culminated in abolition.

The case had gained a great deal of attention amongst the public, so much so that by 1783 a strong anti-slavery movement was being formed. More individual cases such as that of a slave taken to Canada by American loyalists, sparked new legislation in 1793 against slavery, the first of its kind to take place in the British Empire.

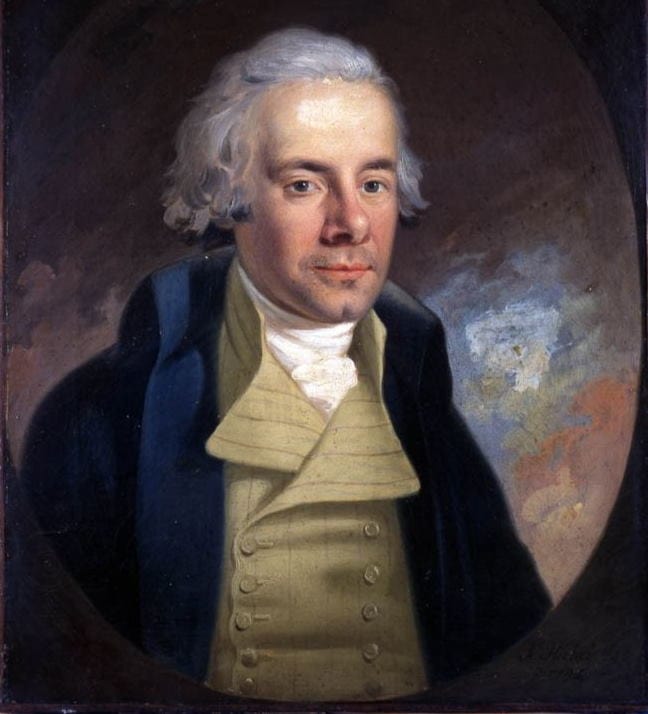

Back in Britain, the abolition of slavery was a cause championed by William Wilberforce, a Member of Parliament and philanthropist who was one of the most important and influential figures. He was soon joined by likeminded individuals who would bring the matter into the public sphere as well as the political sphere.

Other anti-slavery activists such as Hannah More and Granville Sharp were persuaded to join Wilberforce, which soon led to the foundation of the Anti-Slavery Society.

Key figures within the group included James Eliot, Zachary Macaulay and Henry Thornton who were referred to by many as the Saints and later, the Clapham Sect of which Wilberforce became the accepted leader.

On 13th March 1787 during a dinner involving several important figures amongst the Clapham Sect community, Wilberforce agreed to bring the issue to parliament.

Wilberforce would subsequently give many speeches in the House of Commons which included twelve motions condemning the slave trade. Whilst his cause described the appalling conditions experienced by slaves which were in direct opposition to his Christian beliefs, he did not advocate a total abolition of the trade. At this point, however, the biggest obstacle was not the ins and outs of the motion but parliament itself which continued to stall on the matter.

By 1807, with slavery garnering great public attention as well as in the courts, Parliament passed the Slave Trade Act. This was a momentous step, however it still was not the end goal as it simply outlawed the trade of slaves but not slavery itself.

Once enacted, the legislation worked through the imposition of fines which sadly did little to deter slave owners and traders who had great financial incentives in ensuring that the practice continued. With lucrative gains to be made, trafficking between Caribbean Islands would persist for several years. By 1811, a new law would help to curb this practice somewhat with the introduction of Slave Trade Felony Act which made slavery a felony.

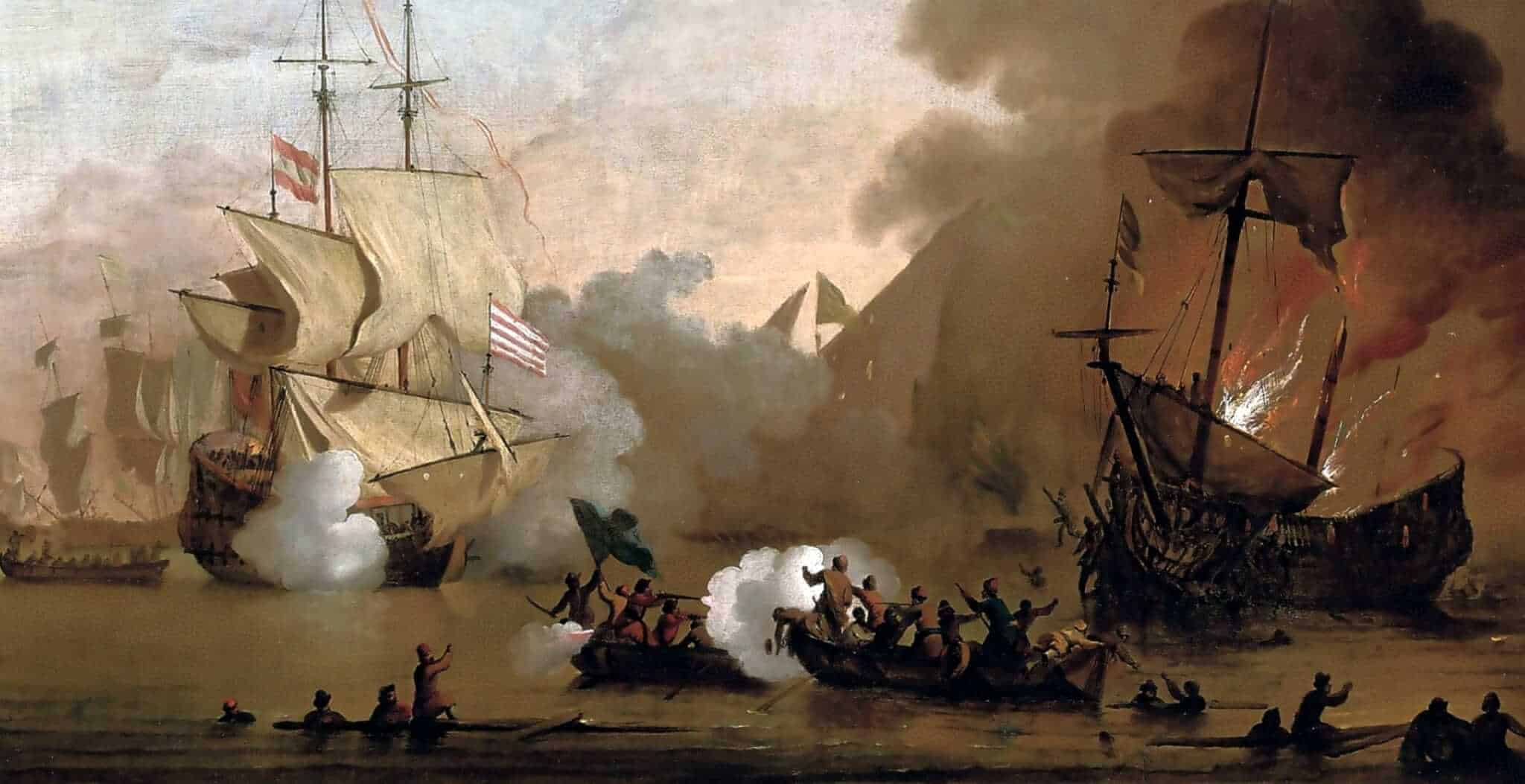

The Royal Navy was also called in to assist in the implementation through the establishment of the West African Squadron which patrolled the coast. Between 1808 and 1860 it successfully freed 150,000 Africans bound for a life of enslavement. However, there was still a long way to go.

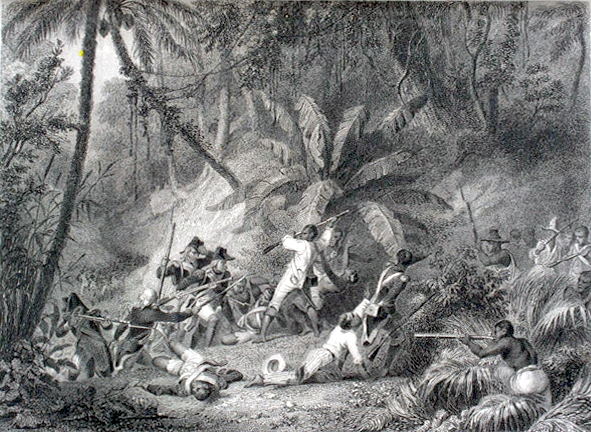

One often overlooked factor in bringing an end to the practice of the slave trade was the role played by those already enslaved. A growing resistance movement was developing amongst the slaves themselves, so much so that the French colony of St Domingue had been seized by the slaves themselves in a dramatic uprising leading to the establishment of Haiti.

This was an era for enacting great social change, the Age of Reason, ushered in by the Enlightenment which brought together philosophies which catapulted social injustices to the forefront of people’s minds. Europe was experiencing great upheaval: the French Revolution had brought with it ideas of the equal rights of man and challenged the previously accepted social hierarchies.

The impact of this new European social conscience and self-awareness also impacted enslaved communities who had always put up resistance but now felt emboldened to claim their rights. Toussaint Louverture leading the revolt in Haiti was not the only example of such a stirring of feelings; revolts in other locations followed including Barbados in 1816, Demerara in 1822 and Jamaica in 1831.

The Baptist War, as it became known, in Jamaica originated with a peaceful strike led by the Baptist Minister Samuel Sharpe, however it was brutally suppressed which led to loss of life and property. Such was the extent of the violence that the British Parliament was forced to hold two inquiries that would make important inroads in establishing the Slavery Abolition Act a year later.

Meanwhile, the Anti-Slavery Society had its first meeting back in the UK which helped to bring together Quakers and Anglicans. As part of this group, a range of campaigns involving meetings, posters and speeches were arranged, helping to get the word out and draw attention to the issue. This would ultimately prove successful as it brought together a range of people who rallied behind the cause.

By 26th July 1833, the wheels were in motion for a new piece of legislation to be passed, however sadly William Wilberforce would die only three days later.

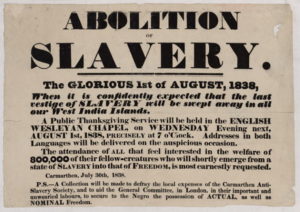

As part of the act, slavery was abolished in most British colonies which resulted in around 800,000 slaves being freed in the Caribbean as well as South Africa and a small amount in Canada. The law took effect on 1st August 1834 and put into practice a transitional phase which included reassigning roles of slaves as “apprentices” which was later brought to an end in 1840.

Sadly, in practical terms the act did not seek to include territories “in the possession of the East India Company, or Ceylon, or Saint Helena”. By 1843 these conditions were lifted. A longer process however ensued which not only included freeing slaves but also finding a way to compensate the slave owners for loss of investment.

The British government sought around £20 million to pay for the loss of slaves, many of those in receipt of this compensation were from the higher echelons of society.

Meanwhile whilst the apprenticeships were enforced, peaceful protests by those affected would continue until their freedom was secured. By 1st August 1838 this was finally achieved with full legal emancipation granted.

The abolition of slavery in the British Empire thus brought in a new era of change in politics, economics and society. The movement towards abolition had been an arduous journey and in the end many factors played a significant role in ending the slave trade.

Key individuals both in Britain and overseas, parliamentary figures, enslaved communities, religious figures and people who felt the cause was worth fighting for all helped to bring about a seismic shift in social awareness and conscience.

Thus, the trajectory of events leading to the abolition of slavery remain a significant chapter in British and global history, with important lessons for humanity as a whole.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 12th June 2019.