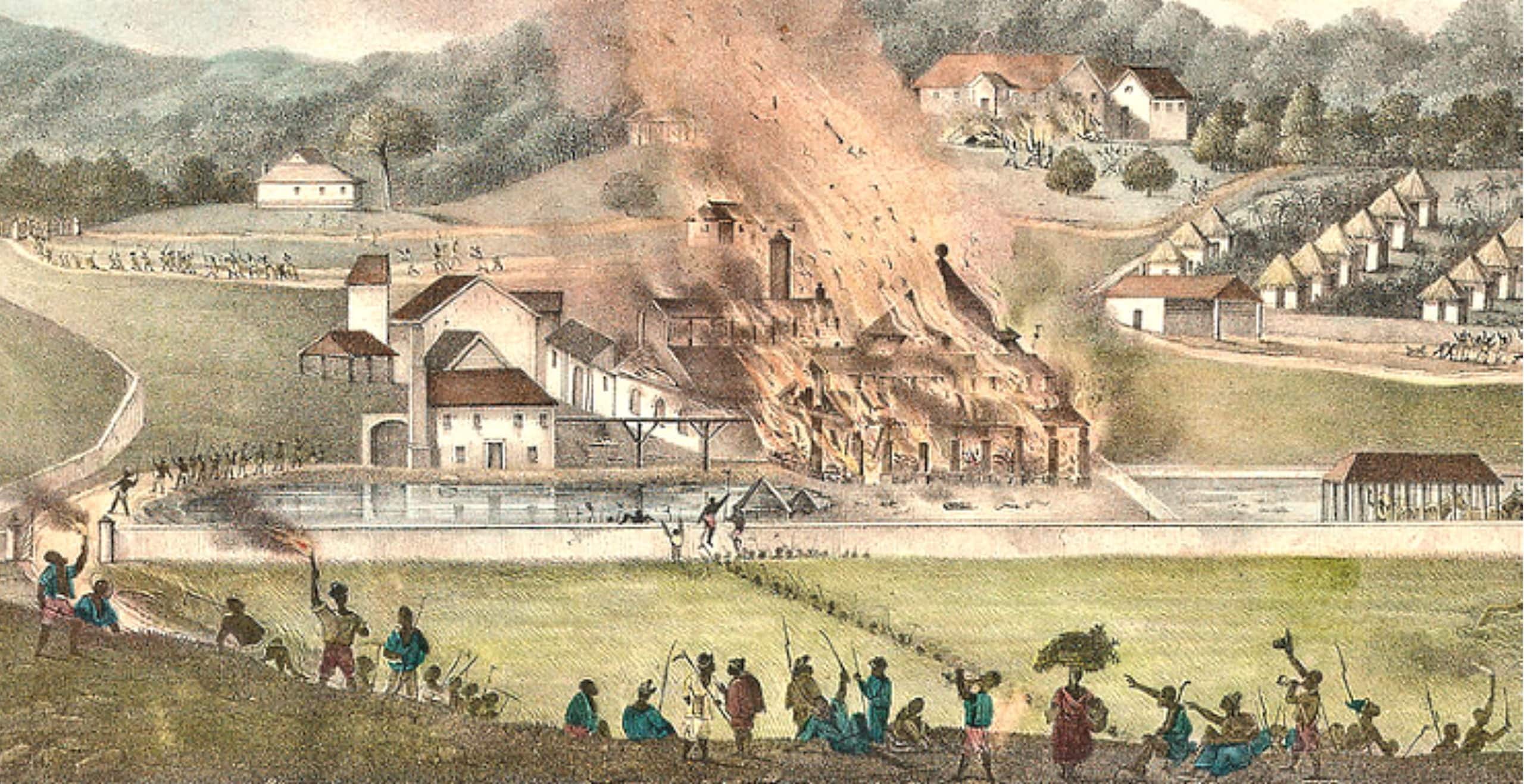

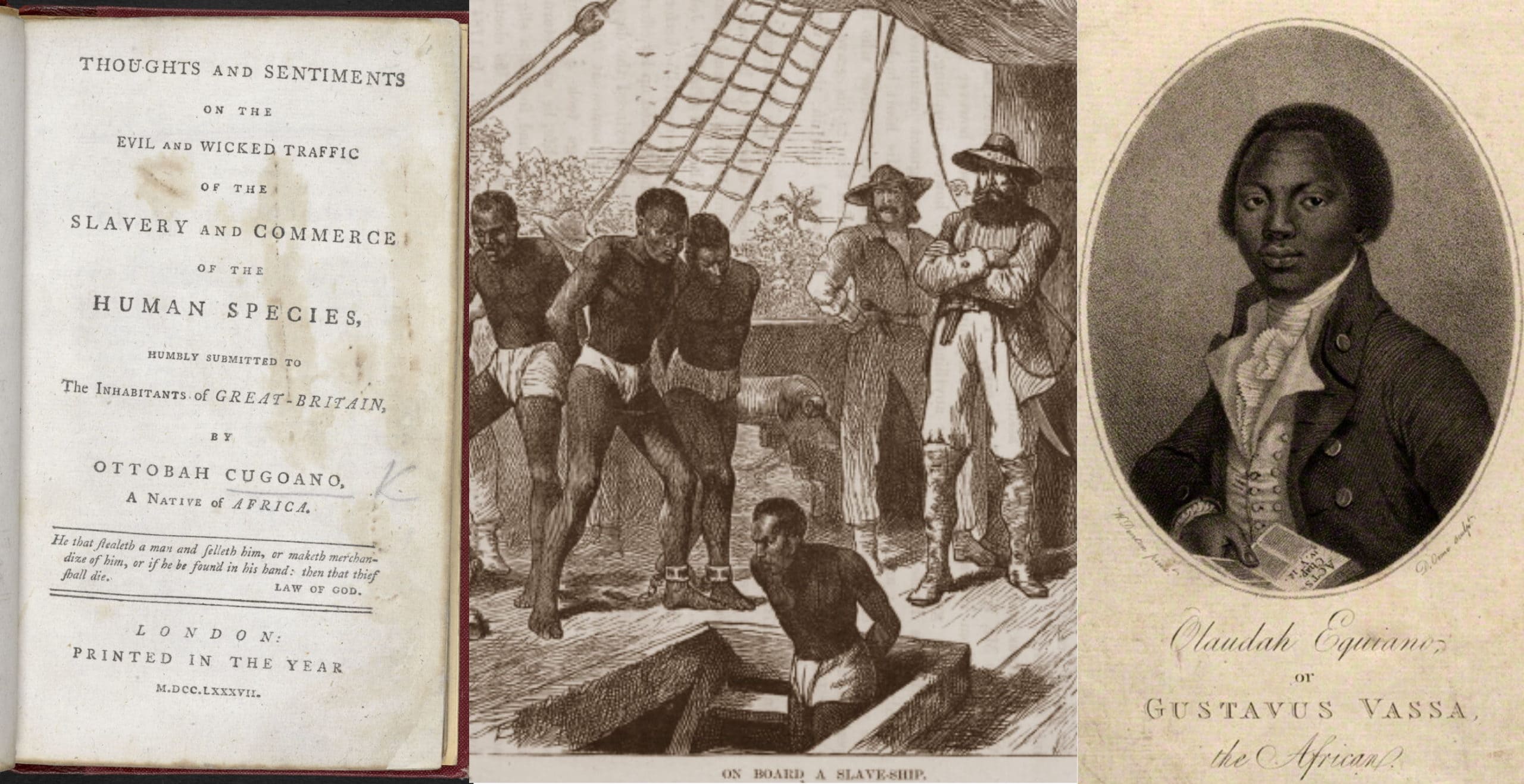

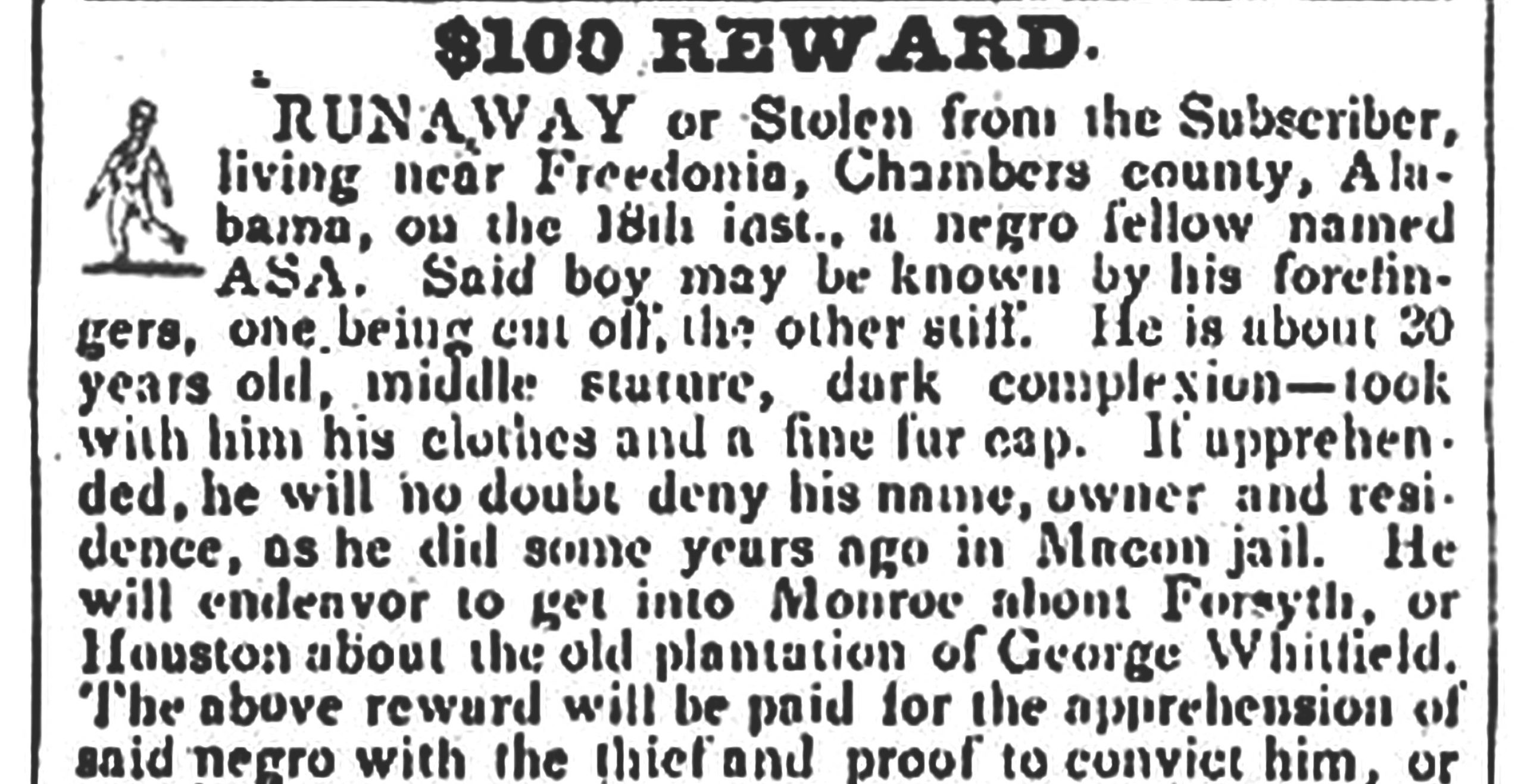

The process of abolishing slavery was a long and arduous one. With many steps taken to formally end the abhorrent practice, campaigners believed the passing of the Slave Trade Act on 25th March 1807 to be a vital step in such a process.

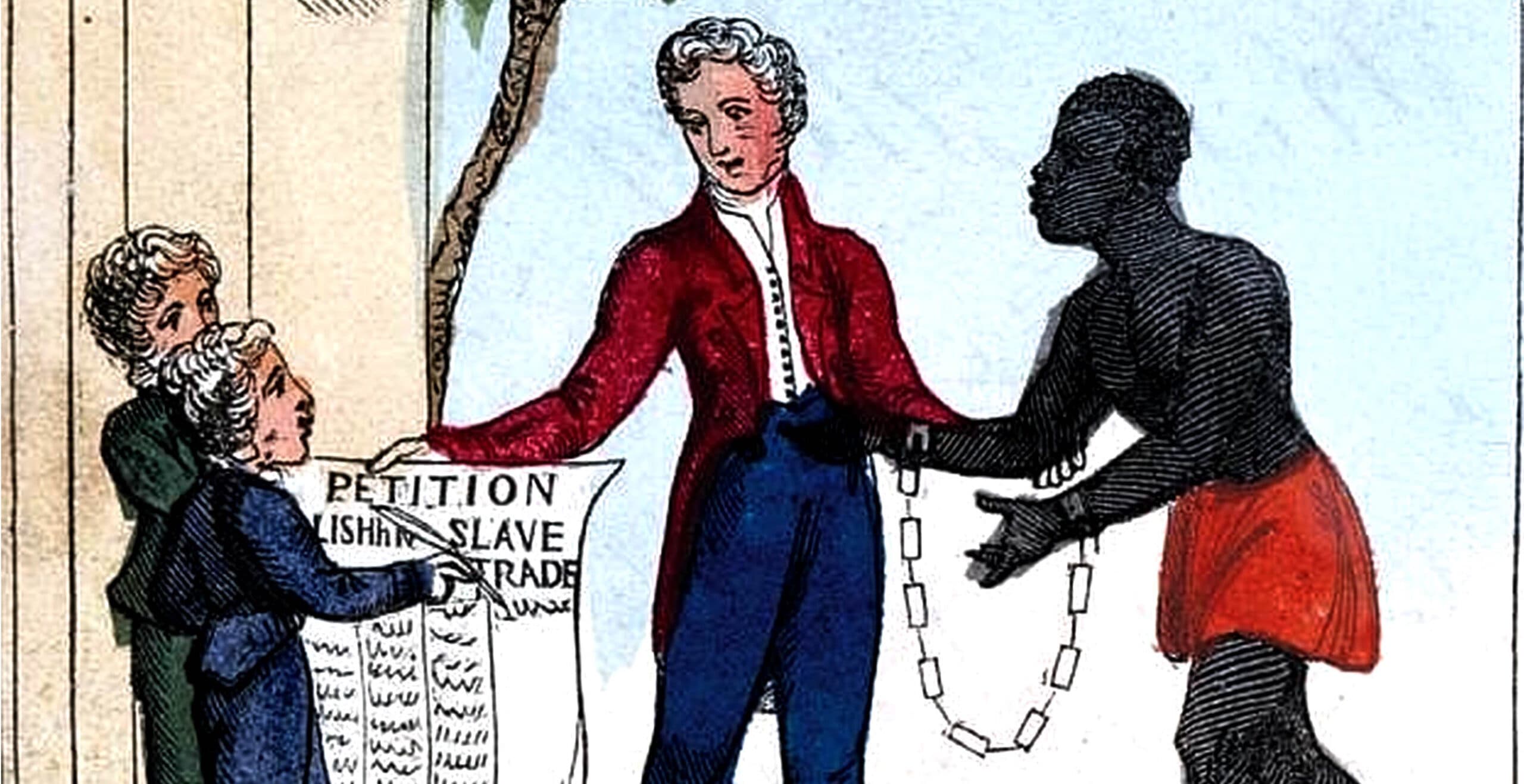

An Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade, as it was officially known, was passed in the United Kingdom Parliament prohibiting the trade of slaves but not the practice of slavery in the British Empire.

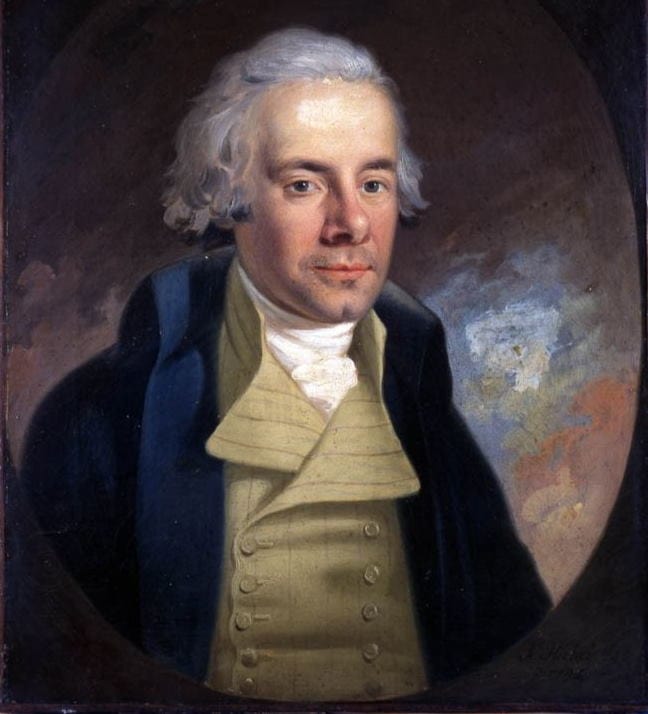

Many of the well-known campaigners such as William Wilberforce extolled the virtues of such an act, as it was seen as a victory for those who had been fighting for the cause for a long time.

Following the passing of the act in parliament in 1807 however, the tangible limitations of implementing such a law was another matter.

It was clear that to end the slave trade, which had provided many individuals with vast amounts of wealth, would be a difficult task to accomplish.

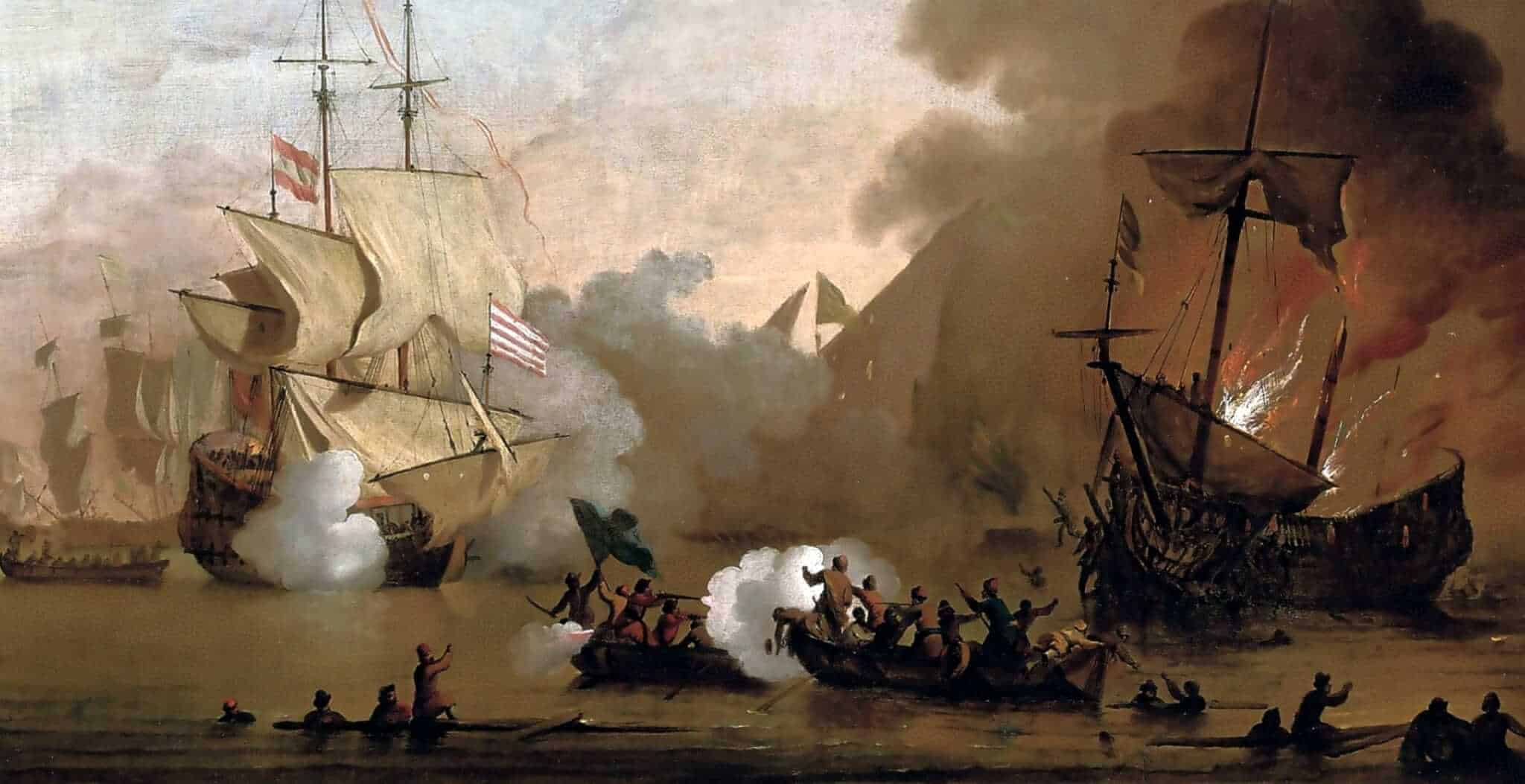

In order to make headway, the following year a squadron, known as the West Africa Squadron (also referred to as the Preventative Squadron), was set up who would become the frontline soldiers in the war on the slave trade.

The newly formed squadron was comprised of members of the British Royal Navy tasked with suppressing the slave trade by patrolling the West African coastline in search of illicit traders; effectively a police out at sea.

Slave trade out of Africa, 1500–1900. Author: KuroNekoNiyah. Licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

In the initial years of its founding, it was based at Portsmouth. However the squadron proved to be understaffed, inefficient, lacking in progress and unequal to the task ahead of them.

In the first few years, not enough priority was given to the anti-slavery agenda, as the Royal Navy were preoccupied with the Napoleonic Wars. As a result, only two ships were dispatched as part of the squadron, contributing to the slow start.

Moreover, precarious diplomatic decisions needed to be considered when tackling the slave traders, particularly in the context of the ongoing Napoleonic Wars.

Whilst the Navy may have found no issue in challenging a slave ship belonging to an enemy nation, tackling others who were England’s allies in the war proved a little more challenging.

Most notably, England’s oldest ally and important supporter in the war was Portugal, which also happened to be one of the largest traders of slaves. Therefore, the stakes were high, not only on the high seas but in the field of diplomacy.

Eventually, owing to their alliance with Britain, Portugal bowed to pressure and signed a convention in 1810 which allowed British ships to police Portuguese shipping.

However that being said, within these stipulations Portugal would still be able to trade in slaves as long as they were from their own colonies, thus demonstrating the slow progress and drawbacks continually facing those who dared to challenge the long and lucrative practice of slavery.

Nevertheless, Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo in 1815 proved to be a turning point, as the defeat of their rival meant that the British could draw on more resources to curtail the activities of the traders and make the squadron into a more effective force.

In September 1818, Commodore Sir George Ralph Collier was sent to the Gulf of Guinea in the 36 gun HMS Creole, accompanied by five other ships. He was the first Commodore of the West Africa Squadron. His task however proved extensive as he was expected to patrol a 3000 mile coastline with only six ships.

As the Napoleonic Wars reached its conclusion, Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, Foreign Secretary at the time, was being pressured by abolitionists such as William Wilberforce to move further towards ending the slave trade.

At the First Peace of Paris Conference in 1814, Castlereagh’s efforts had come to nothing, however he was more successful at the Congress of Vienna some months later.

Whilst countries such as Portugal, Spain and France were initially resistant to his attempts to sign an anti-slavery international agreement, Viscount Castlereagh ultimately proved successful as the Congress concluded with the commitment of signatories to the abolition of the slave trade.

What had begun with reticence ended in legally binding commitments by several nations, including the United States.

This was an important step in demonstrating how Britain’s abolition of slavery agenda, executed on the high seas by the West Africa Squadron, was beginning to influence international legislature and thus pave the way for more action, albeit at a slower pace than many abolitionists would have wanted.

Meanwhile, out at sea the first-hand experiences were raw and unrelenting.

For crew members serving in the West Africa Squadron, conditions were difficult and were marred by constant illness as a result of tropical diseases such as yellow fever and malaria, as well as accidents or at the hands of violent slave traders. Serving on the African coastline, conditions were unhealthy; constant heat, bad sanitation and lack of immunity contributed to a high mortality rate aboard these ships.

In addition, this gruelling experience was made worse by the barbarism witnessed out at sea.

Until 1835, the squadron was only able to seize the vessels which had slaves on board, therefore slave traders not wanting to face fines and capture, simply threw their captives into the sea.

Examples of such experiences were prevalent and were noted by an officer who commented on the amount of sharks as a result of humans thrown overboard in large numbers.

Such scenes of barbarity were, even for nineteenth century sensibilities, a difficult experience to process, as demonstrated by the commodore Sir George Collier who noted that “no description I could give would convey a true picture of its baseness and atrocity”. For those on the frontline of this war on slavery, the images of hardship and human tragedy would have been overwhelming.

On a legal level however, it was soon realised that a system needed to be set up in order to process those who had been caught in possession of slaves. Therefore in 1807, a Vice Admiralty Court was set up in Freetown, Sierra Leone. Only ten years later this would be replaced by a Mixed Commission Court which contained officials from other European countries, such as Holland, Portugal and Spain who would operate alongside their British compatriots.

Freetown would become the epicentre of the operation, with the Royal Navy creating a naval station there in 1819. It was here many of the slaves freed by the squadron choose to settle, rather than suffer the arduous journeys further inland to their place of origin and for fear of being recaptured. Some were recruited for the Royal Navy or West India Regiment as apprentices.

The squadron however faced further challenges, particularly when the slave traders, keen to evade capture, began using even faster ships.

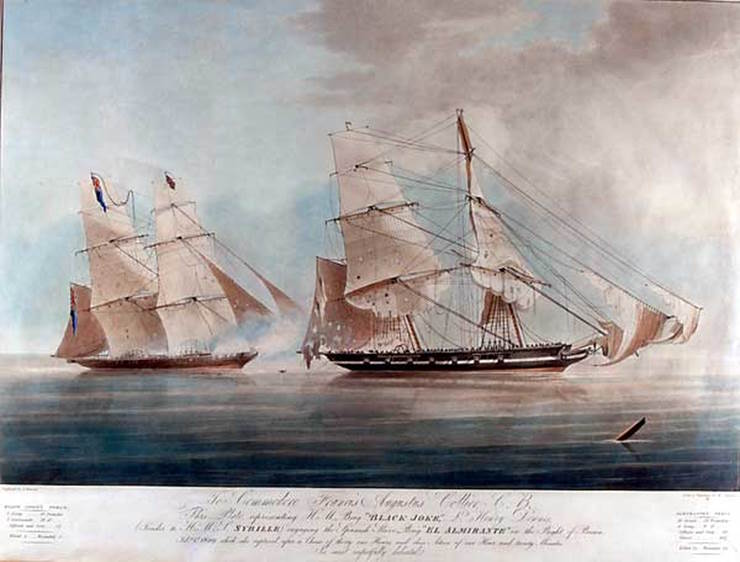

In response, the Royal Navy adopted equally fast vessels, with one in particular proving to be highly successful. This ship was called HMS Black Joke (a former slave ship), which in one year managed to capture eleven slave traders.

In the decades that followed, techniques and equipment were being constantly improved, enabling the Royal Navy to solidify their advantage, particularly with the use of paddle steamers that gave them the ability to patrol rivers and shallower waters. By the middle of the century, around twenty five paddle steamers were being used, with a crew of around 2,000.

This naval operation created international pressure to force other nations to give them the right to search their ships. In the subsequent decades, the Squadron would be responsible for intercepting slave trading across many regions, from North Africa to the Indian Ocean.

Further assistance also came from the United States which added naval power to the West Africa Squadron.

By 1860, it is thought that the squadron had seized around 1,600 ships during the years of its operation. Seven years later the squadron was absorbed into the Cape of Good Hope Station.

Whilst the task of abolishing slavery altogether was an enormous one, over almost sixty years of operation the West Africa Squadron did succeed in halting and disrupting the slave trade.

It accounted for capturing roughly 6-10% of slave ships and as a result freed around 150,000 Africans. In addition, the implementation of the squadron had a positive impact in encouraging other nations to follow suit, with subsequent anti-slavery laws being adopted. Diplomatic pressure prevented several hundred thousand more people from being shipped from Africa.

It also helped to influence public opinion, with frequent newspaper articles detailing the incidents at sea as well as depictions in art. The general public were able to see first-hand the impact and importance of its maritime manoeuvres in combatting this dreadful trade. The campaign was an expensive one however, at its height it is estimated to have cost the Exchequer two per cent of the nation’s GDP. That would be equivalent to today’s entire defence budget.

The West Africa Squadron was one small chapter in a much larger struggle for humanity as a whole to end the barbarity of slavery and send out the message of people before profits.

Crew of ice ship HMS Protector pay their respects to the thousands of sailors of the West Africa Squadron who helped put an end to the slave trade, St Helena, 2021. Photograph by kind permission of the Royal Navy

St Helena is a small British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean that played a crucial part in the fight against slavery. From 1840 for some 30 years, the captains and crews of slave ships captured by the West Africa Squadron were taken to St Helena to be brought to justice at the Vice Admiralty Court. The freed slaves, known as “Liberated Africans”, were given leave to settle on the island or travel on to settle in the West Indies, Cape Town or later, Sierra Leone. However many of the slaves had suffered terribly during their voyages and most of those who died are buried in Rupert’s Valley near Jamestown.

The cost to the Royal Navy was also heavy: one sailor died for every nine slaves freed. They died either in action or of disease. Among the ships lost was the ten-gun sloop HMS Waterwitch which spent 21 years hunting down slave ships until one of the slavers sank her in 1861. A memorial to HMS Waterwitch is situated in Castle Gardens on the island.

On 20th October 2021, the crew of ice ship HMS Protector joined leaders of St Helena in a service of remembrance and thanksgiving for the men of the West Africa Squadron and the slaves they liberated.

Commander Tom Boeckx places a wreath on the monument to anti-slavery sailors who died aboard HMS Waterwitch. Photograph by kind permission of the Royal Navy

Commander Tom Boeckx, HMS Protector’s Executive Officer, praised islanders for welcoming and tending to freed slaves landed on St Helena, at great personal risk given the high levels of disease. He said the men and ships of the West Africa Squadron deserved honouring and remembering, just as much as Nelson, HMS Victory and other more famous contemporaries who faced just as much danger “in pursuit of a better society and world”.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 4th March 2023.

P.S. The campaign cost the lives of more than 1,500 sailors in combat and from disease. Funding is now being sought for a memorial in Portsmouth to commemorate the Navy’s vital role in stamping out global slavery. If you would like to contribute towards it, please go to – https://justgiving.com/crowdfunding/WestAfricaSquadron