As the campaign to bring an end to the slave trade gained real traction by the end of the eighteenth century in Britain, individuals such as Olaudah Equiano and Ottobah Cugoano would prove instrumental in the fight, imparting first-hand accounts of their experiences, reflecting the true cost and reality of what it meant to be enslaved.

With the collaboration of fellow former slaves, who were now free, the men would gather together a community of likeminded campaigners who called themselves the Sons of Africa. The group, now considered to be Britain’s first black political organisation, was made up of educated and erudite individuals who wanted to make their contribution to the abolitionist movement.

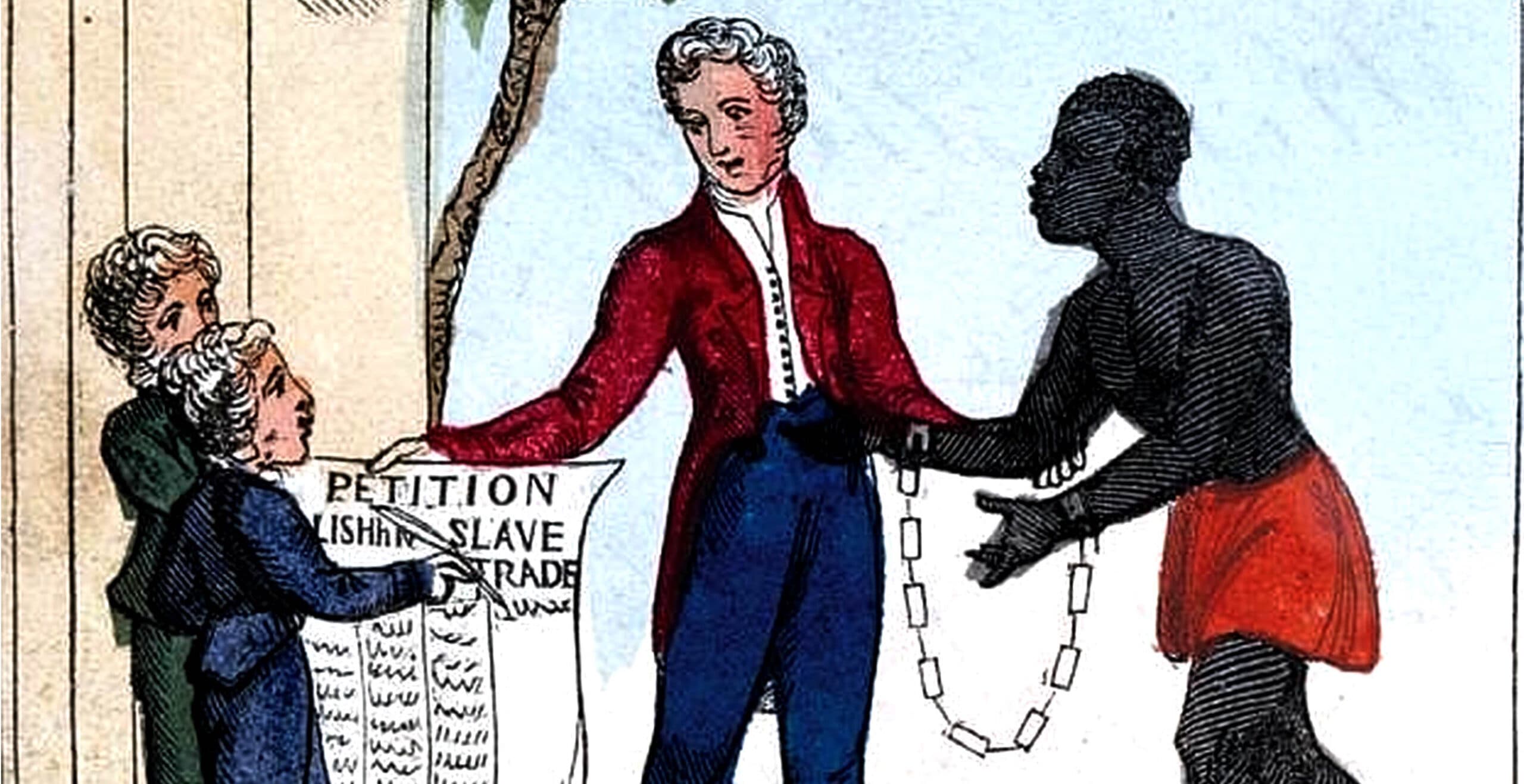

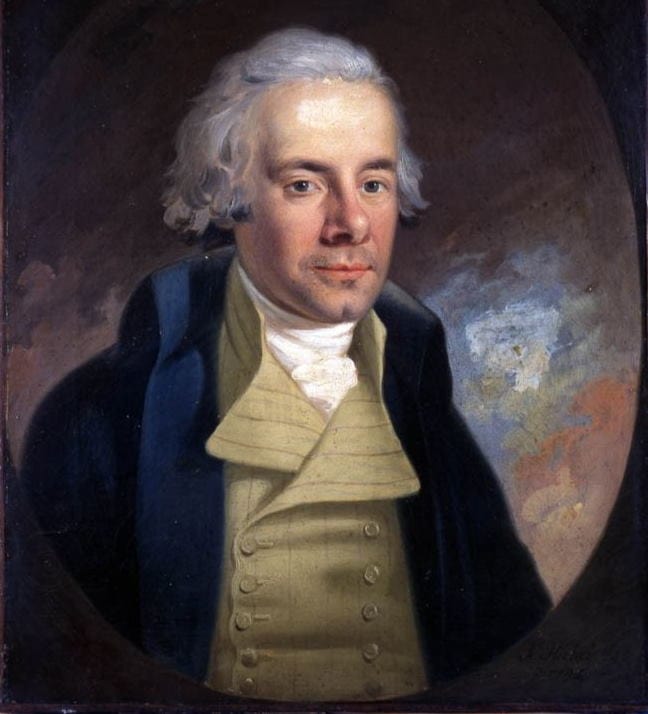

Their actions, together with the likes of William Wilberforce and Granville Sharp, would contribute to the passing of new acts in parliament which would eventually bring about an end to the barbaric trade of humans for profit.

The campaign to end slavery was one fought by numerous individuals including parliamentarians, philanthropists, Quakers, other religious groups, as well as former slaves. Together their actions were able to bring about tangible change as the public gained a new appetite for reform, social awareness and justice.

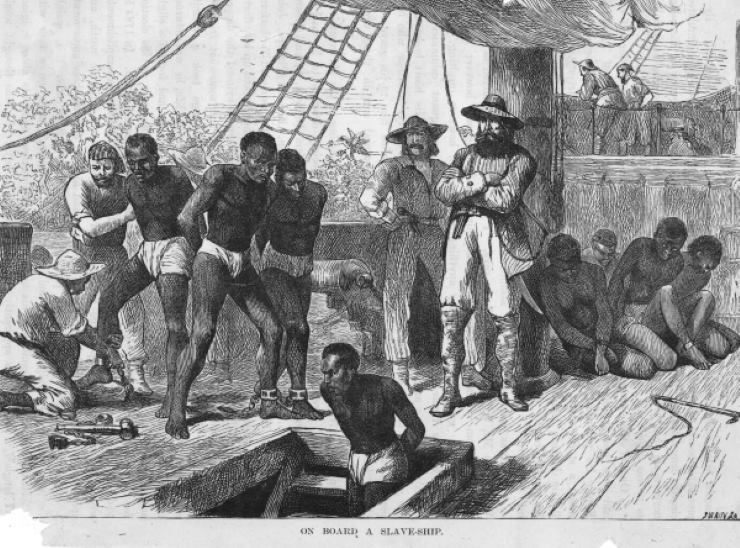

For many centuries the trade in humans across continents had been taking place, leading to great profits for the imperial coffers. With an estimated 3.5 million enslaved Africans being transported across to the Americas between the 1660s and 1807, Britain’s sizeable human cargo came second only to that of Portugal.

The actions of those involved would lead to the largest enforced demographic changes the world has ever witnessed, spanning three continents.

By the late eighteenth century, the transportation of slaves by Britain was reaching its peak, so too were its profits. It was around this time that the general public began to voice concerns about the practices bringing about a moral dilemma for many who had made such substantial financial gains.

This was a time of reawakening in Europe, as changes in public morality and social responsibilities grew, so too did the voices of discontent that Britain could perpetuate such barbaric practices.

By the 1780s the topic appeared on the radar of the House of Commons as a debate took place in parliament with the motion questioning whether the slave trade was contrary to the rights of men as well as the word of God.

In time, various political steps were taken which would gradually contribute to the suppression and eventual abolition of the slave trade.

One of the principal groups involved in instigating this change was the Anti-Slavery Society which arose from the campaigning of Wilberforce, Granville Sharp, Hannah More and many others.

Meanwhile, another very active abolitionist group was emerging called the Sons of Africa. This group was comprised of Africans that had gained their freedom from slavery either by buying their way out or running away from their owner’s household.

At this time in Britain, many Africans were gathered in London with the overall black community thought to number around 10,000, the majority with a slave background. In many cases, some had travelled along with their masters as personal servants.

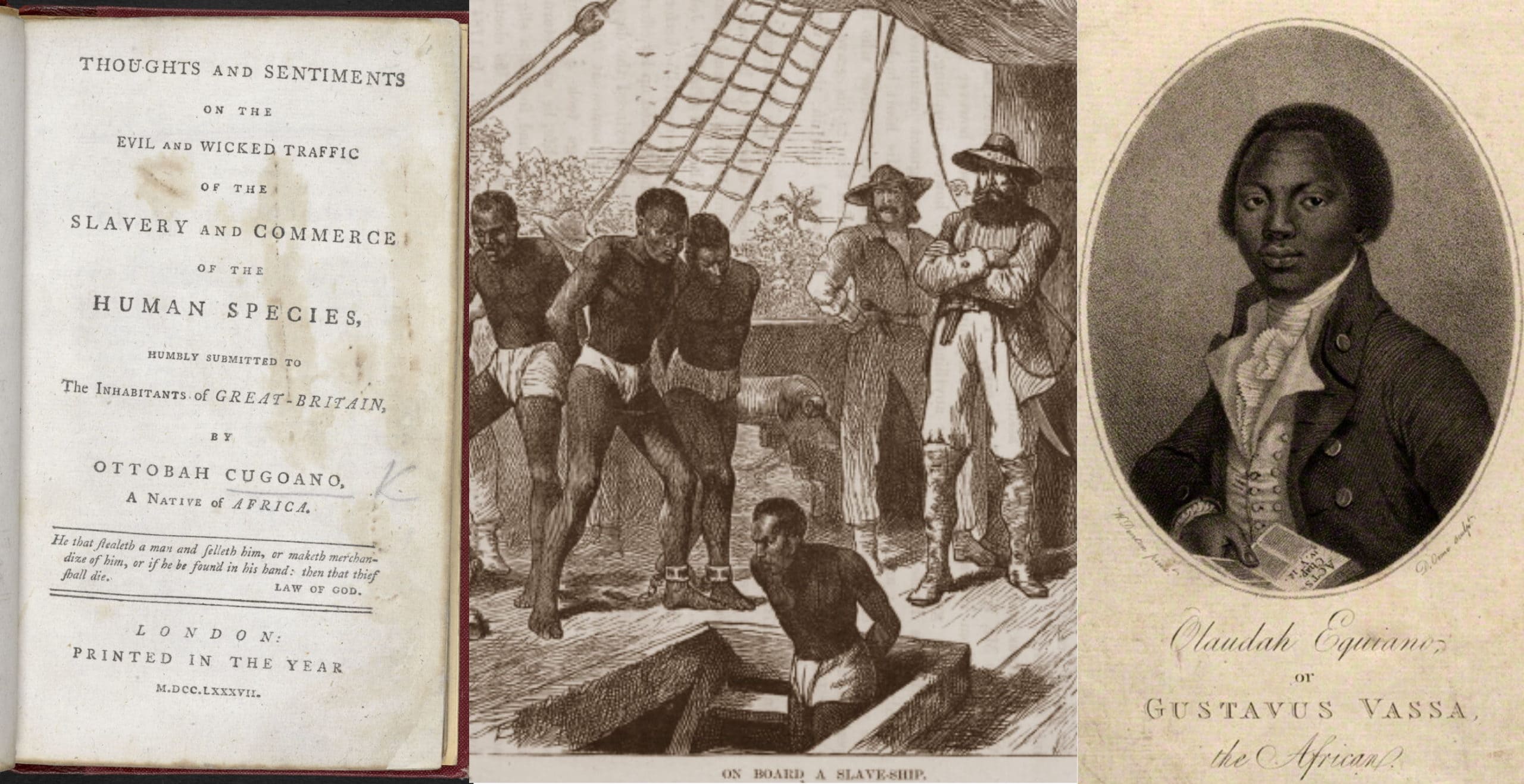

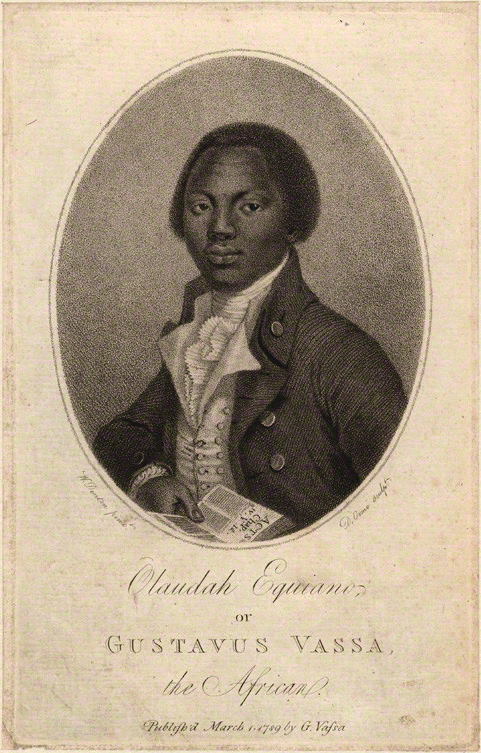

Two of the most prominent members of this anti-slavery group were Ottobah Cugoano, sometimes referred to as John Stuart, and Olaudah Equiano. Their stories would echo the experiences of many like them, sold into slavery as young boys and transported across the Atlantic to work.

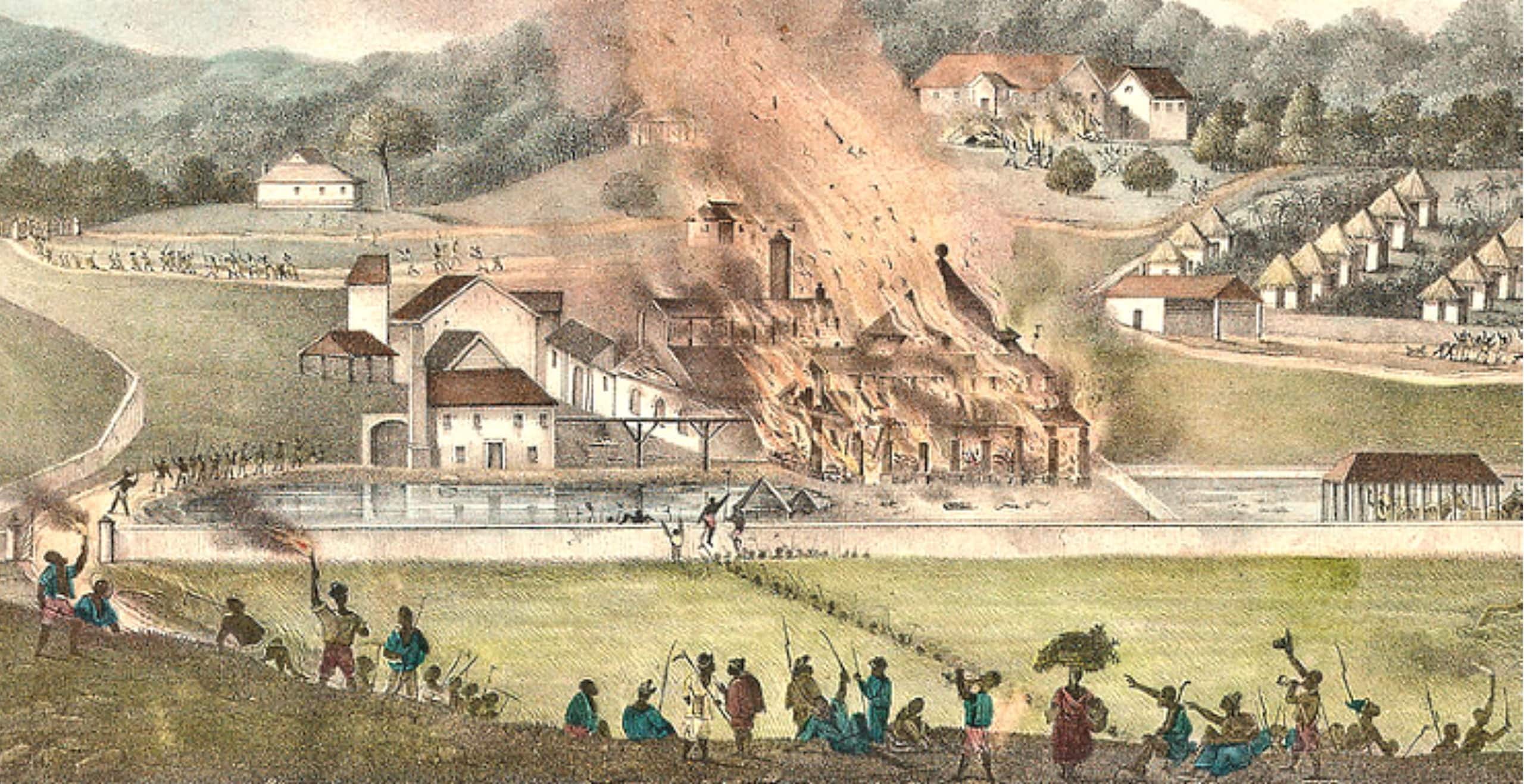

Ottobah Cugoano, originally from Ghana, began his enslavement when he was only thirteen years old, after he and a group of young boys and girls who had been playing in a field were seized by slave-traders and transported to Grenada. After surviving the perilous journey aboard the slave ship he began work in the Lesser Antilles working out in the plantations.

He would later describe the abhorrent mistreatment he experienced for the eight months he was there, witnessing the torture and beatings that many of his peers were subjected to, merely as a way to punish and demean. For those that could bear the hunger no more and who dared to take some sugar cane to eat, a lashing across the face or even teeth pulling was dealt out as a punishment to deter any more dissenters in the midst.

Fortunately for Cugoano, by 1772 his fate would change when he was purchased by a British merchant by the name of Alexander Campbell who would subsequently take him to London where he would offer him his freedom.

By the following year, now aged sixteen, he was baptised at a church in Piccadilly as John Stuart. Now a free man able to work in the city, he managed to gain employment as a servant to Richard Cosway and his wife Maria, who were both artists.

During this time he would become a prominent member of the black community. He would be taught to read and write and soon gained the attention of important and influential public figures such as William Blake and even the Prince of Wales.

He would become increasingly politically active, so much so that by 1786, with the help of prominent abolitionist Granville Sharp, he managed to secure the release of a kidnapped black man called Henry Demane who was bound for the plantations of the West Indies.

Cugoano and fellow Africans, such as friend and fellow campaigner, Olaudah Equiano, would continue to fight for the cause by writing to newspapers and producing memoirs, organising petitions and arranging public speeches in order to spread the message and condemnation of slavery.

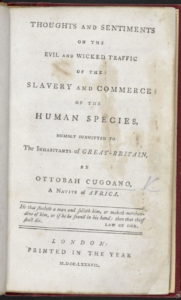

A year later he produced a publication entitled, “Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil and Wicked Traffic of the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species”. His work was inspired by his newly acquired devout Christian values as he called for the abolition of the practice of slavery but also the freedom for all those currently enslaved.

His text was sent to some of the highest authorities in the land including many members of the royal family as well as politicians such as Edmund Burke.

Within his publication he devoted pages to his own first-hand experience, describing how he had felt betrayed by African slave traders who had sold him and other children to European traders.

He would also vividly recall his exact worth, remembering that his value equalled that of a gun, cloth and some lead.

His essay would summarise not only the deficiencies of such a practice but also the imperial ambitions which contributed to it, whilst also heaping praise on the abolitionist movement which was so desperately trying to bring about change.

Whilst his ideas were radical for the time, his essay would also prove to be immensely popular, forced to reprint three times as well as be translated into French.

Similarly, Olaudah Equiano published an autobiography in 1789 entitled, “The Interesting Narrative of the Life of Olaudah Equiano”. His publication would prove to be a sensation, resulting in nine subsequent editions and translations into Russian, German and Dutch. His writing was a hit and helped pave the way for more narratives of this genre.

Equiano’s skill was bringing the topic of slavery to the forefront of the British public conscience.

His experience was enlightening in a different way to that of Cugoano, as he had been taken aboard a vessel by Navy officer Michael Henry Pascal who renamed him Gustavus Vassa. He would go through a few more names after that as well as different owners during which time he gained great experience on the high seas, was taught to read and write and even worked in the trading and commerce business.

In time he had accompanied Pascal during the Seven Years’ War and later arrived in England where he was educated and converted to Christianity. After being sold on two further occasions and transported back to America to work for a Quaker merchant, eventually he was able to buy his freedom.

In 1768, Equiano returned to England and managed to procure work as a deckhand which took him around the world and even as far as the Arctic.

By 1780, now living in London he became more politically active as he joined the Sons of Africa and began socialising with philanthropists who supported the abolitionist cause and who urged him to tell his story.

Whilst Equiano’s literary success would take him on tours around the country, the Sons of Africa would also actively engage with Members of Parliament, many of whom had personal links to the slave trade.

One of the most tangible results came in 1788 when a delegation managed to persuade the MP Sir William Dolben to pass a bill to improve conditions on slave ships. Whilst the Slave Act of 1788 did not end slavery or transportation, each piece of legislation was a small victory in a much larger battle which spanned politics, economics and culture.

The abolition of slavery would prove to be a hard-fought battle as attitudes would take longer to change than political legislation, nevertheless the Sons of Africa would prove to be a living embodiment that slaves had a voice and could use it powerfully against a system that had done so much to silence them.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: July 28th, 2021.