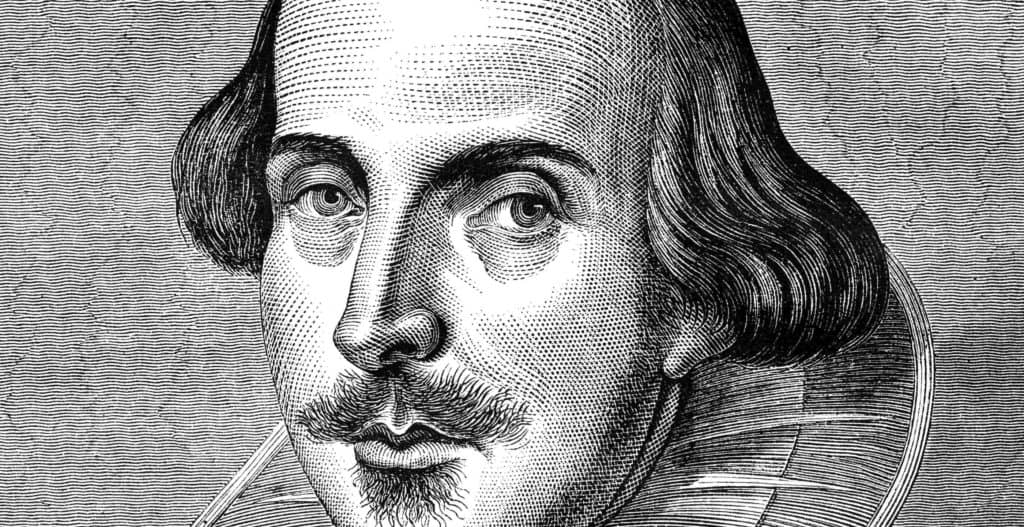

William Blake was a man of many talents: an engraver, poet, writer, painter and mystic.

Whilst his work has captured the imagination of many, he was largely unappreciated in his own lifetime. He worked as an engraver as well as a poet, writer and artist. He is perhaps best known for the poem “And did those feet in ancient time” which in 1916 was set to music by the musician Sir Hubert Parry in the hymn “Jerusalem”.

William Blake created iconic works both in literary and artistic circles and was greatly influenced by the social changes and political context of his era. Original, experimental and mystical, his work continues to enthral centuries later.

His story begins in Soho, London, where he was born on 28th November 1757, the third of seven children. Blake did not come from great wealth: his father worked simply as a hosier but his literary and artistic endeavours were supported by both his parents.

Young William’s formal education was short as he only attended school until the age of ten in order to learn to read and write. However his parents realised his potential and although he left school, he was enrolled in a drawing class in the Strand.

William had a comfortable childhood and was given a great deal of freedom, especially after he finished his formal education. He spent a lot of his time travelling through London and the countryside and at this point he experienced his first vision of “bright angelic wings” in a tree in Peckham Rye. This would be the first of many. Blake’s continuous visions throughout his life would have a prominent effect on his work.

What soon became clear, was that the young boy needed freedom in order to find an outlet to express himself. It was during this time that he was able to read widely, choosing the subjects which were of most interest to him. He rejected the popular literature of his day and favoured other eras such as Elizabethan with the likes of Ben Jonson and Shakespeare dominating, as well as more ancient texts. Blake also had strong religious influences: the Bible became a constant source of inspiration and would feature in various forms in his work.

Blake would benefit early on from artistic influences that would enable him to experiment with different mediums, finding the style that suited him most. His father meanwhile, bought several Greek antiquity drawings for young William to copy through engravings. Through this process he was exposed to a number of renowned artists including Michelangelo, Raphael and Dürer. Blake thus certainly benefited from the support of his parents who financed and facilitated his artistic endeavours.

At the age of fourteen, he was apprenticed to the printmaker James Basire who recognised his natural talent. This was a time of great learning where he could study engraving and find a new passion for medieval art and all things Gothic. This would prove most fruitful, as the drawing of murals in Westminster Abbey helped him to develop his own ideas and fuel his passion for Gothic art.

By the age of twenty-one Blake’s apprenticeship was coming to an end and he subsequently became a journeyman copy engraver to earn a living. He was engaged by booksellers to engrave illustrations for novels they intended to publish, including the likes of ‘Don Quixote’.

Whilst working as an engraver, he was admitted as a student into the esteemed Royal Academy of Art’s School of Design where his works were shown in an exhibition. Nevertheless, Blake did not appreciate the style and approach pioneered by the school’s president, Joshua Reynolds, as he disliked the work of those artists in vogue at the time.

The Gordon Riots, by Charles Green

The Gordon Riots, by Charles Green

Meanwhile Blake found himself caught up in the Gordon Riots when he was swept up by the mob who were heading to Newgate Prison. Blake, who participated in this revolt, was said to have been right at the front during the attack, unsurprising considering he was never one to shy away from confrontation.

In the same year he also found himself arrested for spying, after taking a sketching trip to the River Medway in the south east of England, with a fellow Academy student called Thomas Stothard. This was an area where much of the military happened to be stationed and as Britain was fighting wars against both America and France, the young students were suspected as being spies. It was soon made clear that they were only students and they were subsequently released: a picture by Stothard was used to commemorate the event.

In his private life, he met and married a young woman called Catherine Boucher who became his loyal companion and would assist in the management of his affairs. Her support of her husband was crucial for Blake, however the match was a little surprising as Catherine was illiterate.

The two enjoyed a successful marriage, despite not bearing any children: she appreciated his genius and believed in his visions, whilst he helped her to read and write, as well as teaching her the basic skills of drawing and painting. They supported each other until Blake’s death forty-five years later.

In the meantime, whilst he continued working as an engraver he had not forgotten his other passion, poetry. In 1783 he went on to publish a collection of his poems, composed over a decade long period in his youth.

By now his work was beginning to garner more attention, especially from important individuals such as George Cumberland, who also happened to be one of the founders of the National Gallery.

In 1784 William and his brother Robert went on to open their own print shop and collaborated with the publisher Joseph Johnson, a radical figure whose home became a meeting place for intellectual circles.

Blake’s feelings on the social and political climate was clear: he hoped for revolution, both in America and France. He shared similar views and at times socialised with a range of characters including the American revolutionary Thomas Paine, the feminist Mary Wollstonecraft and William Wordsworth.

Sadly, in 1787 Blake experienced personal tragedy when his brother Robert died of tuberculosis at just twenty-four years old. Having been very close to his brother, he felt the loss very keenly. At this point, his melancholy manifested into further visions which he claimed would lead him to a new style of printing which he called “illuminated printing”.

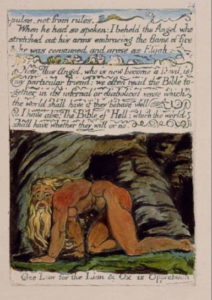

Image from ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’.

Image from ‘The Marriage of Heaven and Hell’.

Also known as relief etching, Blake would use this process in his future work, including some of his most famous creations such as “Songs of Innocence and Experience” and “The Marriage of Heaven and Hell”.

In 1800, Blake accepted an invitation from the poet William Hayley and moved out of London to a cottage in the seaside community of Felpham where he ended up composing “Milton: a Poem” which included in the preface, the inspiration for the subsequent hymn “Jerusalem”.

Unfortunately for Blake his relationship with Hayley soon soured and he began to encounter new difficulties when in 1803 he was arrested for assaulting an officer and was later accused of sedition.

This was at a time when the punishment for sedition was extremely severe; Blake would have feared for his life. Fortunately, Hayley hired a lawyer for Blake and in 1804 he was found not guilty and Blake and Catherine were able to return to London where they stayed for the remainder of their lives.

Upon his return to the capital, Blake started work on “Jerusalem” and began to exhibit his work. Sadly, his work was not well-received and was met with such harsh criticism that Blake plunged into a poor and fragile state of mind, forcing him to withdraw from work.

Throughout his career Blake had been fascinated by mythology and mystism, further enhanced by his intense following of the philosophy of the Swedish theologian and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg. Throughout his life, he experienced great mood swings, highs and lows so severe that many labelled him as insane. However some recognised his artistic potential, including George Cumberland who introduced him to the Shoreham Ancients, a group who like Blake, rejected artistic trends of their era and embraced a spiritual approach.

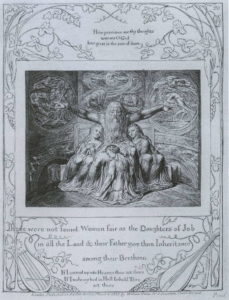

Illustration from the ‘Book of Job’.

Illustration from the ‘Book of Job’.

It was at this time that the now sixty-five year old Blake began creating illustrations for the “Book of Job”. He worked on engraving twenty-one designs and found himself increasingly busy, receiving commissions for works of Shakespeare, the Bible and Milton. In 1824 he began working on an ambitious project to create 102 watercolour illustrations for Dante’s ‘Divine Comedy’. Sadly, the project would be left incomplete when he passed away on 12th August 1827.

William Blake was an eccentric, outstanding, radical figure who left behind some of the most iconic works of literature and artistry of his time. Today his work continues to provoke, inspire and engage.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.