Eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded for the defence of Rorke’s Drift in the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879, the most VCs for any action in the history of the British Army. Private Frederick Hitch was one of the 11 defenders rewarded for his bravery. Richard Rhys Jones’ account of the engagement is told in the form of a memoir by Private Hitch…

Private Frederick Hitch

“England’s hot August sun reminded me of South Africa as I awaited Queen Victoria in the garden of Netley Military Hospital, Southampton. She arrived wearing a flowing black dress and looked just like her pictures in ‘The Illustrated London News.’

As Her Majesty pinned the Victoria Cross on my tunic, an orderly read out this citation:

“It was chiefly due to the courageous conduct of Private Frederick Hitch and Corporal William Allen that communication was kept up with the hospital at Rorke’s Drift. Holding together at all costs a most dangerous post, and raked with enemy rifle fire from behind, they were both severely wounded. But their determined conduct enabled the patients to be withdrawn from the hospital. After their wounds were dressed, they continued to serve ammunition to their comrades throughout the night.”

He didn’t mention that I was 23 years old at the time and one of 11 Londoners in the 2nd Battalion of the 24th (Warwickshire) Regiment.

As the Queen pinned the medal to my tunic and muttered a few words of congratulation, a sharp pain shot through my right shoulder and my mind went back to that terrible day seven months before when the Zulu impis attacked our outpost at Rorke’s Drift, about 25 miles from Dundee in Natal, South Africa.

It was 22nd January 1879 and our ‘B’ Company of the 2nd Battalion had the boring job of guarding a supply depot and the sick and wounded patients in the hospital. They called it a hospital but it was actually a ramshackle building that Irishman Jim Rorke had built after he bought the farm on the Natal bank of the Buffalo River in 1849.

Swedish missionary Otto Witt, with his wife and three young children, bought the farm after Rorke committed suicide in 1875. He turned it into a mission station, used the original homestead as a residence and named the mountain behind it the Oskarberg after the Swedish king.

Surgeon-Major James Reynolds RAMC had to cram about 30 patients into the building’s 11 small rooms that were separated by thin partitions of mud bricks with fragile wooden doors.

Poor old Gunner Abraham Evans and his mate, Gunner Arthur Howard, were handily placed in the room next to the outside toilet because they both had a bad dose of diarrhoea. Other blokes had leg injuries, blistered feet, malaria, rheumatic fever and stomach cramps from drinking polluted water.

Under the supervision of Assistant Commissariat Officer Walter Dunne and Acting Assistant Commissariat Officer James Dalton, we turned the chapel building into a commissariat store and off-loaded supplies from the wagons. Our working party worked up a good sweat carrying 200lb bags of meilies, wooden biscuit boxes each weighing a hundredweight, smaller wooden boxes packed with 2lb tins of corned beef, and wooden ammunition boxes each containing 60 packets of 10 cartridges. Little did we know that those bags and boxes would save our lives a few hours later……

Round about noon we heard the rumble of field guns and the faint crackle of rifle-fire from the direction of Isandlwana 10 miles away. That meant that Lord Chelmsford’s main force, which had crossed the Buffalo River on January 11, was engaging Cetewayo’s Zulu impis, and my mates of the 1st Battalion were seeing some action.

Just before 2 p.m. two riders arrived with the awful news that a gigantic Zulu impi had destroyed the Isandlwana camp, killing most of the defenders, and they were now heading for us at a fast trot.

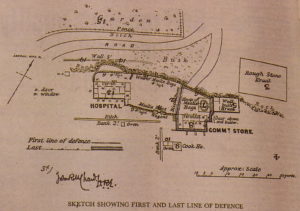

Our commanding officer, Lt. John Chard, was as stunned as the rest of us and I overheard him talking to Lt. Gonville Bromhead, his second-in-command, about whether we should fight or retreat. It was Jim Dalton, a former colour-sergeant with lots of experience in South Africa, who tipped the scales. He reckoned it would be suicide to retreat and suggested we use two wagons and the boxes and sacks from the store to build fortifications between the buildings.

How right he was! Lt. Chard summoned our Company and the 400 men of the Natal Native Contingent and we built the entrenchments in record time. A line of biscuit boxes was placed across the compound from the store to the northern breastwork as a second line of defence, and inside that we built a redoubt of mielie bags 8 ft. high for a final stand.

Lt. Gonville Bromhead

Hearing that the Zulus were getting close, Mr Witt rode off with an injured officer towards Helpmekaar, closely followed by the entire Natal Native Contingent! That left only 141 men to defend our outpost, including the 36 hospital patients, so I reckon only 105 men were fit enough to fight.

I was brewing tea at 4 p.m. when Lt. Bromhead told me to climb onto the thatched roof of the hospital to see what was happening. When I got up there I saw that the Zulus were already on the Oskarberg behind us preparing to attack. When he asked how many, I shouted back: “Between 4,000 and 5,000, sir.” And a joker below yelled: “Is that all? We should manage that lot very well in a few minutes!”

I marvelled at the British sense of humour in the face of grave danger as I watched the black mass extending at a run into their fighting formation. Some of the Zulus crept along under the cover of rocks above us and slipped into the caves, where they began firing, trying to dislodge me from my perch.

A Zulu induna (chief) appeared on the hill and signalled with his arm. As the main body of Zulus began sweeping down on us I took a shot at him, but it missed. I warned Gonny that they would surround us in a short time, so he at once ordered everyone to man their posts.

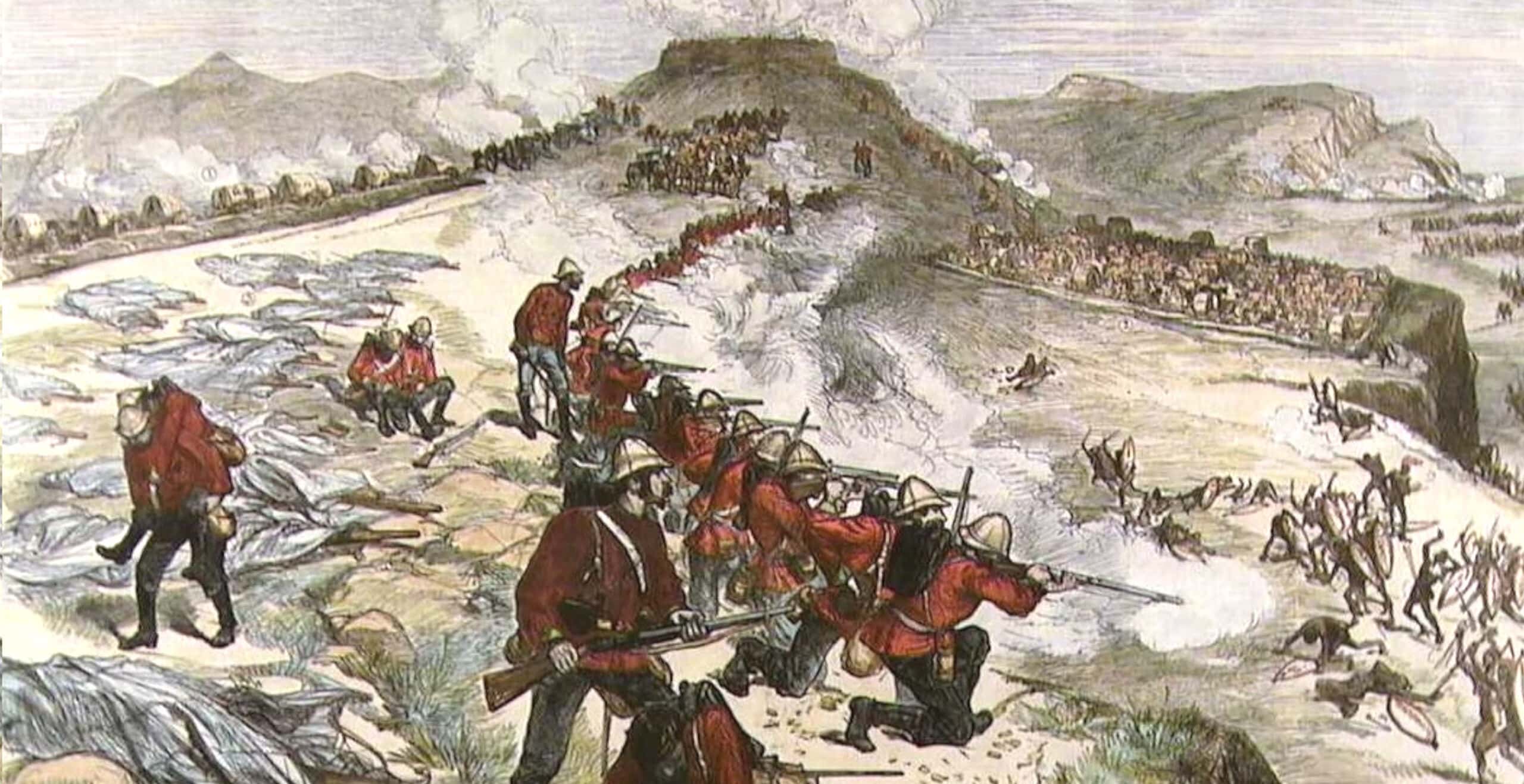

Chard gave the “Open fire!” when the Zulus were 500 yards away, and the first volley thundered from behind the cattle kraal walls and the loopholes of the hospital and store. There was no cover for the Zulus except for a drainage ditch and the cookhouse field ovens. Some of them circled to the eastern end of the kraal, seeking an opening, while those with rifles retreated to the lower terraces of the mountain and fired at us.

Their shots were wildly inaccurate but occasionally a bullet struck home as some of the defenders engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the enemy.

I slid down from the roof, fixed my bayonet and took up a firing position in an open space as our deadly work began.

It looked as if nothing would stop the storming warriors pushing right up to the hospital veranda, but they were repulsed by our bayonets. Some managed to leap into our area before they were shot or skewered and their bodies were then heaved back over the wall.

During the struggle a huge Zulu saw me shoot down his mate. He sprang forward, dropping his rifle and assegai, and seized hold of my Martini-Henry with his left hand and the bayonet with his right. He tried to tug the gun from my grasp but I had a strong grip on the butt with my left hand. I stretched out my right hand for the cartridges lying on a wall, shoved a bullet in the breech and shot the poor wretch.

Time and time again the Zulus charged, clambering over their own dead, but the sloping ledge of soft sandstone and the barricade above it on the north wall were too high and they could do little but cling to the front and thrust upwards with their assegais. They grabbed at gun barrels and bayonets, hacking and shooting, until they fell back into the garden below, many protected from our rifle fire by the wall and the bodies of their own dead, and this enabled them to prolong the engagement for 12 hours.

They then turned their attention to capturing the hospital, setting the thatched roof alight by throwing flaming assegais onto it. As panic mounted inside the burning building, the Zulus broke down the doors and killed the hapless patients in their beds. It was becoming difficult to repulse the swarming Zulus as they kept up a heavy fire at front and rear, from which we suffered very much.

When the Zulus invaded the hospital, Gonny Bromhead, me and five others took up a position on the right of the defensive line where we were exposed to the cross-fire. Lt. Bromhead took the middle and was the only man who wasn’t wounded. Corporal Bill Allen and me were wounded later but the other four blokes with us were killed. One of them was Private Ted Nicholas who got a bullet in the head that sprayed his brains onto the ground.

Bromhead and me had it all to ourselves for about an hour-and-a-half, the lieutenant using his rifle and revolver with deadly aim as he kept telling us not to waste one round. The Zulus seemed determined to remove us both and one of them leapt over the parapet with his assegai aimed at Bromhead’s back. I knew my rifle wasn’t loaded but when I pointed it at the Zulu, he took fright and fled.

The enemy then tried to set fire to the commissariat store and charged up madly, despite the heavy losses they’d already suffered. It was during this struggle that I was shot. The Zulus were pressing us hard, many of them mounting the barricade, when I saw one pointing his rifle at me. But I was busy with another warrior facing me and I couldn’t avoid being hit. The bullet slammed into my right shoulder and I keeled over with the pain. The Zulu would have assegaied me had Bromhead not shot him with his revolver.

“Good old Gonny,” I thought. He’d returned the favour I’d done him a couple of hours before.

With the Zulu battle cry of “Usuthu!” and the crack of rifle shots ringing in my ears, I lay helplessly on the ground as blood gushed from my wound. Gonny said: “I am very sorry to see you down.”

“You get on with it, sir!” I mumbled. ”Don’t worry about me. We’re still holding them.”

He helped me remove my tunic and tucked my useless right arm inside the belt around my waist. Then he gave me his revolver and, with him helping me to load it, I managed very well.

By this time it was dark and we were fighting with the aid of light from the burning hospital, which was much to our advantage, but our ammunition was running low. I was helping to serve out cartridges myself when I became thirsty and felt faint. Somebody tore the lining out of a coat and tied it round my shoulder but I couldn’t do much as I was so tired. In fact, we were all exhausted and the ammo was being rationed.

I crawled over to Cpl. Allen, who’d been shot in the left arm, and we leaned our backs up against the hospital wall to take a breather. Chard ordered everyone to withdraw behind the wall of biscuit boxes, and that’s when the 14 patients still alive began climbing out of the hospital window six feet above us.

Bill Allen with his good right arm and me with my left arm helped them down as best we could and they crawled or were carried behind the barricade. Bill fired at the Zulus lunging round the front of the hospital as our men behind the boxes kept a steady covering fire to keep the enclosure clear.

Trooper Hunter of the Natal Mounted Police was too crippled to walk and was dragging himself across the compound towards the entrenchment on his elbows when a Zulu leapt over the back wall and plunged an assegai into his back.

Private Robert Jones was the last man out of the window, joining Allen and me in the 30-yard dash across open ground to the barricade. The patients and newly wounded had been dragged inside the mielie-bag redoubt, where Dr Reynolds was attending to them.

Pte. George Deacon propped me against the biscuit boxes and said jokingly: “You should be safe here. These army biscuits will stop any bullet!” Then he got serious and said: “Fred, when it comes to the last, shall I shoot you?”

I declined, saying: “No, mate, these Zulus have very nearly done for me, so they can finish me off.”

After Dr. Reynolds attended to my wound by the light of the burning hospital I slept fitfully because the pain was excruciating.

It was after midnight before the rushes of the Zulus began to subside, and long after 2 a.m. on 23 January when the final charge came. They then sank down behind their own dead and kept a desultory fire at us until 4 a.m. when the last flicker of light from the burning thatch faded – and their assault seemed to die with it.

When it was all over, only 80 British soldiers were still standing. They were all exhausted and their shoulders were badly bruised by the continuous pounding of recoiling rifles. Twenty thousand cartridge cases lay scattered among the paper packets in the yard, which left the defenders with only 300 rounds at the end of the battle!

Chard sent out a few scouts at 5 a.m. and 370 Zulu bodies were counted around the post. Our own casualties were 15 killed and 12 wounded, but two of them died from their wounds later. I was one of the lucky ones and felt very thankful to God for leaving me in the land of the living.

When the sun came up, Dr. Reynolds began picking 36 pieces of shattered shoulder blade from my back and told me that my fighting days were over.

The impi was spotted on the Oskarberg at 7 a.m. squatting down beyond our rifle range, but when they saw Lord Chelmsford’s approaching column they trotted down to the river and disappeared into Zululand.

I don’t remember much after that, except that Lord Chelmsford and his force arrived at breakfast time and His Lordship spoke very kindly to me while Dr. Reynolds dressed my wound.

I was shipped back to England on the ‘SS Tamar’ and, after being examined by a medical board at Netley on 28 July 1879, I was informed that I would be invalided from army service on 25 August.”

But not before this proud soldier was decorated by his Queen on 12 August 1879.

FOOTNOTE: Frederick Hitch married in 1880 and became a horse-and-cab driver in London, later graduating to motorised taxis. The Rorke’s Drift hero died of pneumonia at the age of 56 on 6th January 1913 and 1,000 London taxis joined his funeral procession to Chiswick cemetery, where he was buried with full military honours on 11th January – the 34th anniversary of Chelmsford’s advance into Zululand in 1879. The London Taxi Association later struck a special Frederick Hitch Medal to be awarded for bravery. Chard and Bromhead were also among those who won Victoria Crosses.

By Richard Rhys Jones. Richard Rhys Jones’s historic novel “Make the Angels Weep” is available as an e-book from Amazon Kindle.

Published: January 22, 2021.