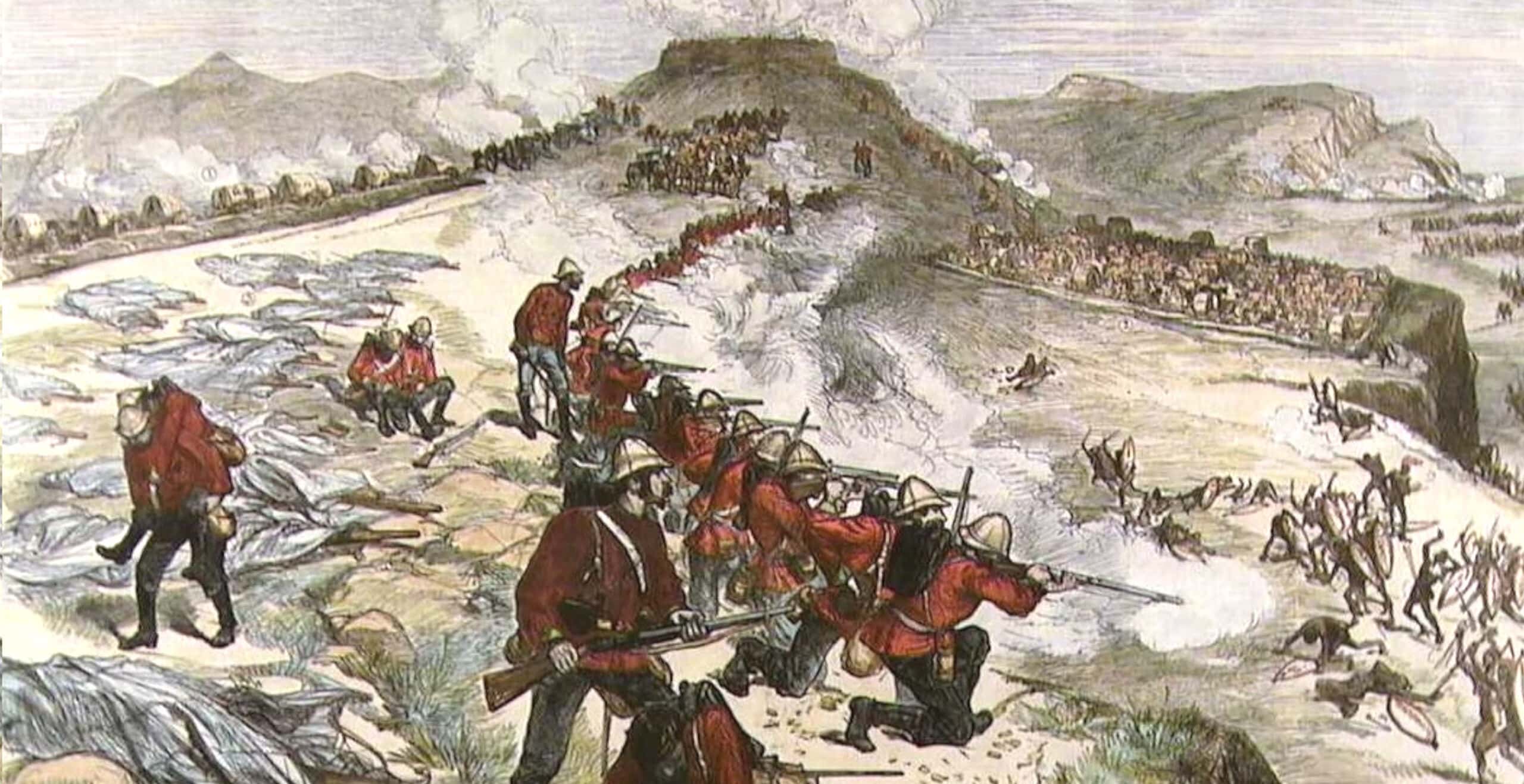

Although one of the lesser-known actions of the Anglo-Zulu War, the Battle of Kambula on 29th March 1879 avenged the British defeat at Isandlwana, established the superiority of the invading force and became the turning point of the war.

Fighting from a secure defensive position on a hill 5 miles from the town of Vryheid in the colony of Natal, a British force commanded by Colonel Henry Evelyn Wood, VC, fought off 22,000 Zulu warriors.

Historians recorded that the defeat completely sapped Zulu morale, as their 2,000 fatalities were double the number that died at Isandlwana on 21 January.

With the lesson of Rorke’s Drift uppermost in his mind, Col. Wood was well prepared when scouts informed him that a huge impi was nearing Kambula.

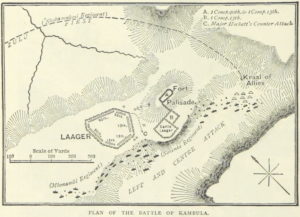

His camp had been established on a steep-sided plateau. A hexagonal laager of wagons tightly locked together by chains was formed and a stone cattle kraal built, both of which were ringed by trenches and earth parapets. A stone redoubt was erected on the summit, a palisade blocked the gap between the kraal and the redoubt, and four 7-pounder field guns defended the northern approaches.

Under Wood’s command were 1,238 infantry, 638 mounted men and 121 Royal Engineers and Royal artillery, but 88 were ill and unable to fight.

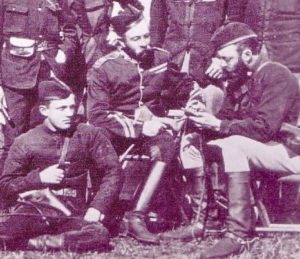

Leading the colonial riders of the Frontier Light Horse was dashing Lt.-Col. Redvers Buller, whose courageous act the day before was to earn him a Victoria Cross. When three men under his command were found to be missing after a night sortie against a superior force, Buller did not hesitate to return to the scene in darkness and brought them safely to camp with yelling Zulus less than 100 yards behind him.

Col. Evelyn Wood (middle), commander of the Kambula garrison, and Lt. Col. Redvers Buller, commander of the Frontier Light Horse, confer in the field with Staff Officer Major C. Clery (left).

Col. Evelyn Wood (middle), commander of the Kambula garrison, and Lt. Col. Redvers Buller, commander of the Frontier Light Horse, confer in the field with Staff Officer Major C. Clery (left).

All was ready at Kambula by 12-45 p.m. and the defenders calmly awaited the terrifying Zulu onslaught. Col. Wood had drilled his men to be in their positions in less than two minutes so he insisted that they eat a meal before going into action.

The tents were struck and reserve ammunition distributed as the impi drew closer, in five great columns composed of nine regiments, the majority of whom had fought at Isandlwana.

Many were armed with Martini Henry rifles taken from the dead, but counting against them was the fact that they had not eaten since leaving Ulundi and were tired from jog-trotting for three days. They split into their familiar right and left horn formation, worked their way around the camp perimeter and sat down beyond gun range to smoke dagga to boost their strength.

Col. Wood knew that those who fought at Isandlwana arrived in the vicinity the day before the battle and slept the night concealed in a nearby valley, so they’d had time to recover after the long trek from Ulundi. But today the enemy would be denied the advantage of a rest period.

Wood readily agreed with Buller’s suggestion that he and 30 of his mounted troops should ride out and provoke the Zulus. When a gap was opened for them, they rode straight at the right horn, dismounted at a few hundred yards and fired one volley.

The effect was instantaneous. Eleven thousand Zulus sprang up and swarmed forward with a mighty roar as the FLH fled back with assegai-brandishing warriors in hot pursuit. Unfortunately for three horsemen, a wide patch of swampy ground slowed down their steeds and they were caught and speared to death.

The infantry went into action when Buller’s men returned and fired concentrated volleys. The 7-pounders caused havoc with exploding shrapnel shells, checking the Zulu advance at 300 yards. Enfilading fire from riflemen in the laager and redoubt soon forced them to fall back to the cover of a rocky outcrop in the north-east.

With their strategy disrupted, the Zulus were unable to complete the encirclement of Kambula hill, allowing the garrison in the northern and western salient to repel the foe’s advance from the opposite quarter.

At 2-15 p.m the Zulu left and centre again attempted to develop their belated attack. Using dead ground below the ridge to the south, and undaunted by the heavy fire, they came at the defenders in a series of great waves. Buoyed by a belief that witchdoctors’ potions had made them immune to bullets, they threw themselves recklessly at the barricades and were mown down by shrapnel fire and volleys from the infantry defending the laager’s south face.

At one stage some Zulus breached the outer defences and charged across the plateau to attack the entrenched positions. Their war cries of “Usutu!” mingled with bugle calls, cries of the wounded and dying, and the thunderous crash of rifle and artillery fire.

A few reached the laagered wagons and crawled between the wheels, only to be bayoneted or shot dead by the defenders.

Wood, who had stationed himself between the laager and redoubt, was not averse to taking an active part in the fight himself and was restrained by his officers when he attempted to go to the aid of a wounded trooper who had been shot outside the redoubt.

Minutes later, seeing that Private William Fowler, a member of his personal escort, was unsuccessful in trying to shoot a Zulu commander, he grabbed the rifle from Fowler and, aiming at the induna’s feet, dropped him with a bullet in the stomach. Wood then potted two more Zulus by aiming low and returned the carbine to Fowler with instructions to adjust the sights.

About 40 Zulus with rifles climbed to the rim of the ravine and began firing at the defenders in the cattle kraal, forcing their withdrawal into the redoubt. Helped by a thick smoke-screen from hundreds of black powder cartridges, Zulus took control of the kraal until Wood ordered two companies of the 90th Light Infantry to re-take it with a bayonet charge. Although hampered by 2,000 terrified oxen, the troopers pushed a wagon out of the way to provide a clear run, formed a line with bayonets fixed and forced the Zulus back into the ravine.

The attack on the redoubt was likewise repulsed at 3 p.m. and, as the Zulus withdrew, gunners of the Royal Artillery poured round after round directly into them. The retreat gave riflemen an opportunity to spread out all along the crest to unleash their own deadly volleys at the warriors below.

A few groups of desperate Zulus attempted feeble charges but were mercilessly cut down until the carnage was sickening to see.

About 5-30 p.m., when the weary and dispirited survivors were slinking away, Col. Wood sent Buller and three companies of mounted colonials in pursuit, and the retreat became a rout.

Urged by their officers to “remember your dead colleagues and show no mercy,” the riders exacted a savage revenge on the retreating horde, firing their carbines at them one-handed from the saddle. The FLH were followed by infantry and African auxiliaries on foot who combed the field and killed every Zulu lying wounded or hidden.

The chase continued for seven miles and the bloodbath only ended at sunset when it began to rain.

The estimated Zulu death count was 2,000, while the British and their allies lost a mere 83 killed or fatally wounded.

Kambula was the decisive battle of the war. It nullified the Zulu victory at Isandlwana, weakened the Zulu resolve to defend their territory at all costs and proved that cowhide shields and assegais were no match for light artillery and quick-firing Martini Henry rifles.

With his much-feared army a spent force after Kambula until their final defeat at the Battle of Ulundi on 4 July, King Cetewayo fled from his capital and hid in the Nkandla Forest. But he was eventually discovered, arrested and banished to Robben Island in Table Bay where he learnt that his kingdom was being carved up and awarded to chiefs who opposed his Usutu faction.

English-born Richard Rhys Jones is a veteran South African journalist specialising in history and battlefields. He was the night editor of South Africa’s oldest daily newspaper “The Natal Witness” before going into tourism development and destination marketing. His novel “Make the Angels Weep – South Africa 1958” covers life during the apartheid years and the first stirrings of black resistance. It is available as an e-book on Amazon Kindle.

Published: March 28th 2022.