Superstitious troops of Lord Chelmsford’s Central Column experienced a feeling of approaching doom when they arrived at Isandlwana in the British colony of Natal on 21 January 1879 and saw that the conical hill was shaped like the sphinx on their regimental badge.

Cap badge of the 24th Regiment

Cap badge of the 24th Regiment

The Zulu name for the promontory with precipitous rock on three sides describes the shape of a cow’s smaller stomach, but to the men of the 24th Regiment of Foot its silhouette at dawn became a sinister omen when a low-lying black cloud touched its peak and turned blood-red.

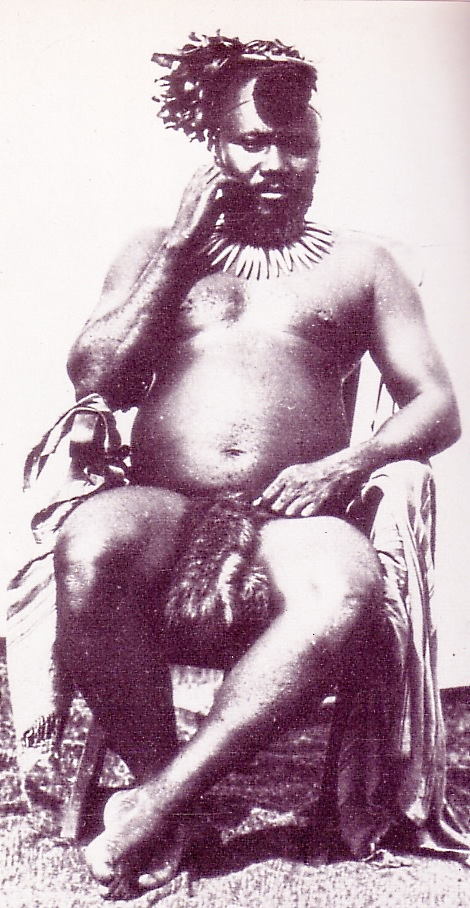

Seized from the Boers in 1842, the colony was populated by British settlers who justifiably felt uneasy about the Zulu King Cetewayo’s 33,000-strong army.

In 1877, with an ambitious vision of expanding its empire in South Africa, Great Britain had annexed the Transvaal Republic adjoining Zululand’s northern border. And late in 1878, after defeating the Xhosas to end the 9th Border War in the Cape, Lt.-Gen. Frederic Thesiger (Lord Chelmsford), the commander-in-chief of Queen Victoria’s forces in Southern Africa, was ready to deal with the Zulu threat.

He devised a three-pronged attack, with the main central column crossing the Buffalo River at Rorke’s Drift, another column advancing on the Zulu capital of Ulundi along the coastal road from Durban, and a third force on the left flank fording the Blood River 35 miles to the west.

On 11 December 1878 a Zulu delegation was presented with an ultimatum demanding that a British official be installed in Ulundi; that missionaries be allowed into Zululand; and that the Zulu army be disbanded within 30 days.

Upon receiving these demands, Cetewayo sent envoys to Natal in the hope of avoiding hostilities, but they were treated with indifference and sent home.

After the king failed to respond, the invasion began at 2 a.m. on 11 January 1879 when British regiments and Colonial volunteers used pontoons to get across the Buffalo River from Natal into Zululand. It took 13 hours for the great mass of men, animals and wagons to complete the crossing over the rain-swollen river and rock-strewn terrain where there were no roads.

The vanguard was briefly checked next day by a Zulu impi (group of warriors) defending a kraal (homestead) four miles from the drift, when two men of the Natal Native Contingent (NNC) were killed and 20 wounded for the loss of 30 Zulus.

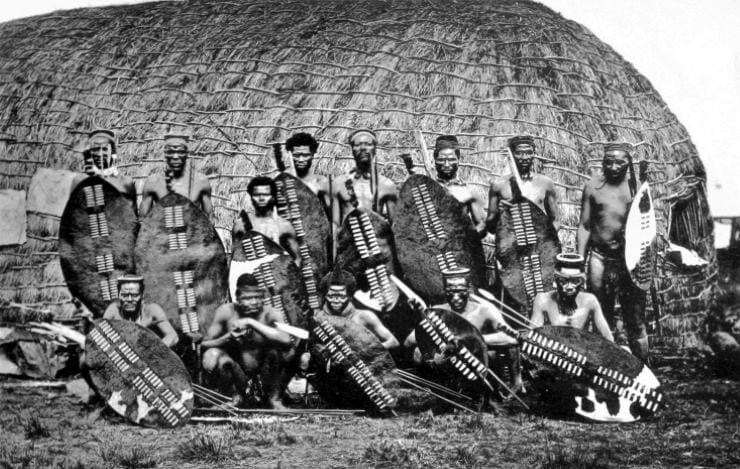

Alerted by his spies, Cetewayo assembled 12 regiments numbering 20,000 on 17 January and, after being well fed, every warrior swallowed a magical brew concocted by witchdoctors to make them immune to enemy bullets. The king exhorted them to “eat up the Red Soldiers” and sent them off late in the afternoon.

The army covered nine miles on the 18th and a similar distance on the 19th, and spent both nights at military kraals. On 21 January they arrived in a valley beyond the Nqutu range where they remained hidden.

Lord Chelmsford and his entourage rode to Isandlwana on 16 January and found that the site commanded a good view of an open plain about eight miles long and four miles wide, but it was pitted with appallingly deep dongas (dry watercourses). On either side of the plain were two almost-parallel ranges of hills – the Nqutu on the left and the Ndhlazagazi to the right.

Over the next five days 120 wagons came up the difficult track from Rorke’s Drift and parked on the higher slope behind the 300 tents of the corps to which they were attached.

Friendly Boers had warned Chelmsford of the Zulus’ extraordinary mobility, their capacity for concealment, and their ability to stage large-scale movements with perfect timing, and advised him to place his wagons in laager (circular) formation.

Colonel Richard Glyn, the battle-experienced commander of the Central Column, also suggested a laager, but Chelmsford replied: “It’s not worthwhile and will take too much time.” He told Glyn that Lt.-Col. Henry Burmeister Pulleine, an administrator who had never been in action, would be in charge of the camp’s defence, and he (Chelmsford) was to accompany Glyn and take command of the Central Column.

It was therefore the general himself who chose the principal actors and set the scene for the great and tragic drama about to be played out on the sun-scorched veld.

Late on 21 January a scouting force discovered a strong force of Zulus about 12 miles from Isandlwana and the sightings were reported to Chelmsford by the officer in charge, who added that he would bivouac that night and await reinforcements.

After hearing the messenger, Chelmsford made the fateful decision to split his force in two. He gave hurried orders to Pulleine and sent a rider to Colonel Anthony Durnford at Rorke’s Drift telling him to advance on Isandlwana with his Natal Native Contingent. Durnford was senior to Pulleine by four years and, although a Royal Engineer, he preferred an alternate role as a dashing cavalry officer, despite losing the use of his left arm in a skirmish with rebel tribesmen in 1873 when an assegai thrust severed nerves in his forearm.

At first light on 22 January Chelmsford rode through the mist to confront what he believed was the main impi, taking with him Glyn, six companies of the 2nd Battalion of the 24th Regiment, four field guns and a squadron of mounted infantry.

Left to defend the camp were five companies of the 1st Battalion of the 24th, a company of the 2nd Battalion, 27 Natal Carbineers, 21 Natal Mounted Police and two artillery pieces, a total of 850 white soldiers. They were later reinforced by Durnford’s 850 untrained and poorly armed NNC infantrymen, who were distinguished from their feared adversaries by strips of red cloth wound around their heads.

The column was no sooner out of sight at 7-45 a.m. than Zulus appeared on the nearby hills. Buglers sounded the “Fall in” and the white-helmeted Redcoats took up positions in front of the tents as Pulleine dispatched a note to Chelmsford reporting that the camp was about to be attacked.

Zulus played hide-and-seek until 10-30 a.m. when Col. Durnford arrived with his 250 mounted men, with the NNC infantry lagging behind. He and Pulleine met for a quick breakfast and Pulleine repeated Chelmsford’s orders: “Stay in camp and defend it if attacked.”

Durnford replied that, if Chelmsford felt satisfied that the camp’s defenders could beat off an attack, he and his mounted troops intended to prevent the Zulus seen on the nearby hills from intercepting Chelmsford’s column out on the plain.

The Zulus’ tactics were clearly meant to make the British split their forces and then to pounce upon the weakest section. It was then that Pulleine should have pulled his troops back into tighter defensive positions instead of posting them far in front of the tents where they were dangerously exposed.

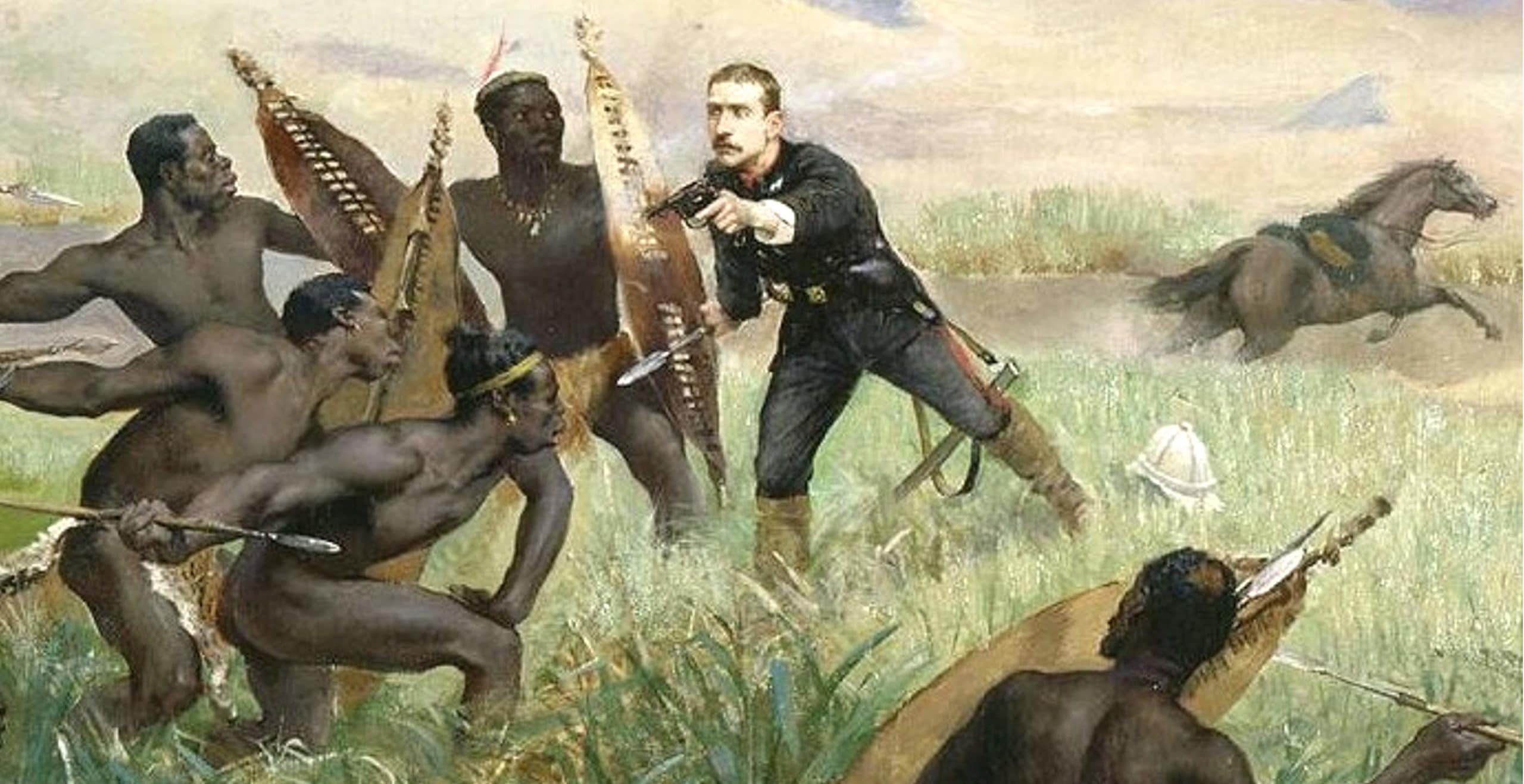

Warriors of the Zulu regiments lurking in the nearby valley were eager to attack when ordered by their indunas (commanders). They wore plumed headdresses and around their waists were monkey-skin kilts over a beshu (codpiece). Each man carried stabbing assegais, a knobkerrie (heavy club) and an ox-hide shield identifying the warrior’s regiment. A few were armed with obsolete rifles and only the indunas rode horses.

By contrast, the invaders’ thick uniforms of red, blue or black corduroy or serge were totally unsuited to South African summer temperatures of 30 degrees C or more. They wore heavy army boots and were weighed down by 70 rounds of ammunition. Confident about their breech-loading Martini Henry rifles and 22-inch-long bayonets, the infantrymen were supported by 320 cavalrymen, mainly Colonial volunteers.

When Pulleine’s note reached Chelmsford at 9-30 a.m. he immediately sent a man with a telescope up a nearby hill. The officer was well aware of the rule that tents should be collapsed when an enemy was sighted so, when he observed that they were still standing, he reported that nothing seemed amiss. Chelmsford realized it would take at least three hours for his force to return to camp, by which time the situation would have been resolved one way or the other, so he continued his own search.

At 11-30 a.m Durnford and his men sallied forth, but within 15 minutes they were under attack and forced to make a fighting retreat.

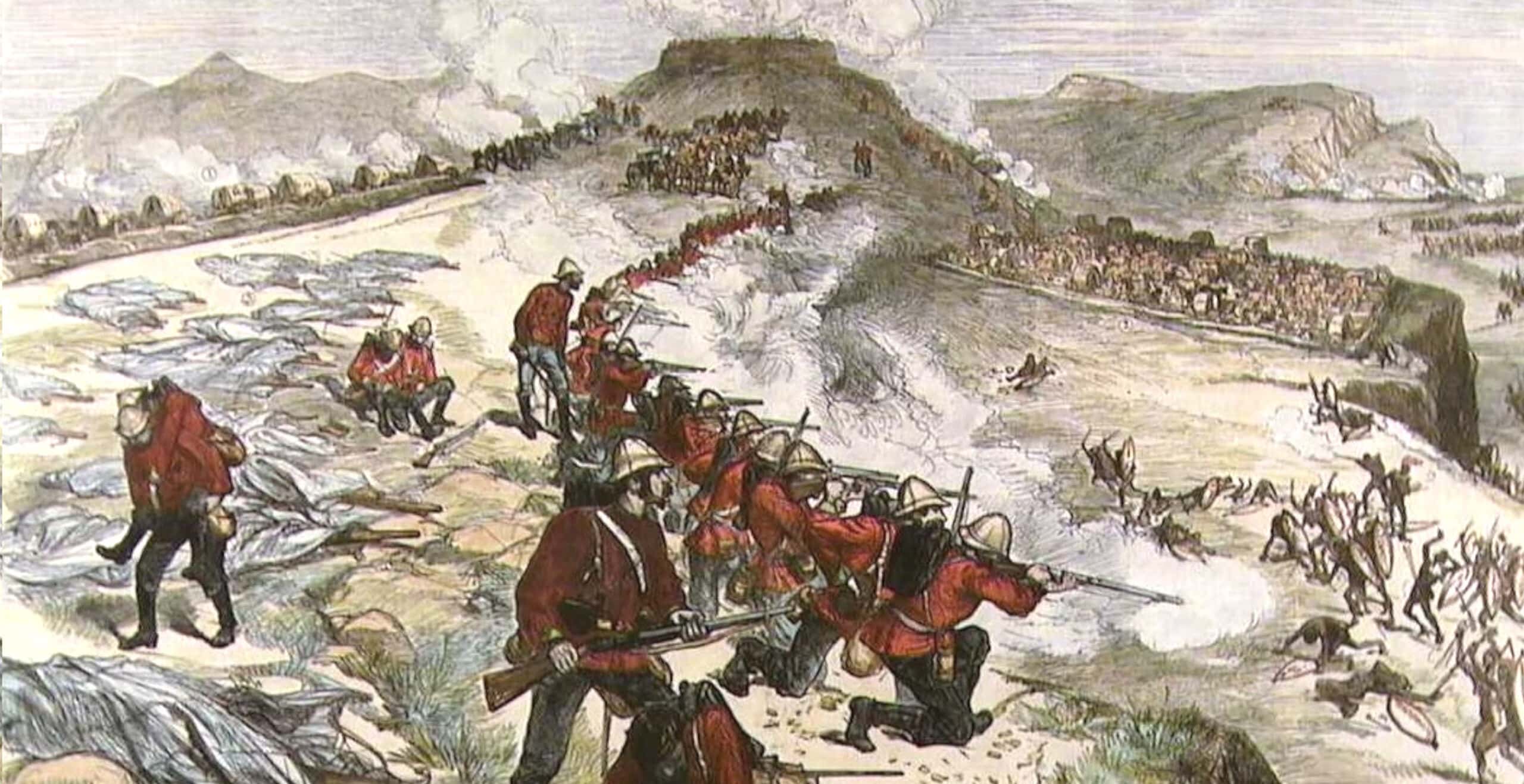

The main assault began at noon when 20,000 Zulus streamed quickly and steadily down the four-mile-wide Nqutu spur, humming loudly like a swarm of bees.

Pulleine deployed his three remaining companies into line on the left of the camp and two of the seven-pounder artillery guns opened fire, causing great havoc with shrapnel. The thinly spread defenders kept up a terrible barrage from their positions in front of the camp and they saw Zulus “falling in heaps.” But as those in front were shot down, others took their places shouting: “We will trample you to death!”

Durnford’s group in a donga on the right front of the camp was joined by Colonial volunteers and they kept about 5,000 Zulus at bay for half an hour. But as they fired steadily at the “chest” of the Zulu formation the extension of the “horns” was being made to surround them. The middle of the crescent-shaped formation was 500 yards deep and the ground in front of the camp was thick with yelling warriors.

Meanwhile, as the right horn surged nearer on the camp’s extreme left flank, the horrified men of the Natal Native Contingent stripped off their distinguishing red bandannas and fled en masse, leaving a gap through which the enemy poured.

Soldiers were surrounded before they could fix their bayonets and were quickly shot, stabbed or bludgeoned to death. Some rallied and fought to the last, their desperate resistance being later revealed by heaps of 50 or 60 dead soldiers.

After an hour of fierce fighting the defenders ran out of ammunition and were slaughtered. Within 10 minutes not one man was alive in the British camp. When a defender fell he was thrown onto his back and his stomach ripped open with an assegai. It was the custom to release an enemy’s spirit in this way, as Zulus believed that, if they neglected to do so, they would themselves die of a swollen belly.

Every man was disemboweled, some were scalped, and others subjected to even ghastlier mutilations. A drummer boy was hung by his heels on a wagon and his throat cut. Even horses, mules, goats and dogs in the camp were butchered in a sheer glut of blood.

The carnage was awful to see, as “Daily News” correspondent Archibald Forbes reported when he accompanied an expedition to bury the dead four months after the battle.

“All the way up the slope I traced the ghastly token of dead men in the fitful line of fight. It was like a long string with knots in it, the string forming the single corpses, the knots of clusters of dead where, it seemed, little groups might have gathered to make a hopeless gallant stand.”

Durnford’s body lay in the grass on the camp’s right flank, the long moustache still clinging to the withered facial skin. He had died hard, the central figure of a knot of brave men who had fought around their leader to the bitter end. In a ring around him lay a dozen assegai-riddled bodies. It was clear to Forbes that they stood fast by choice when they could have escaped on their horses.

When he got back to Isandlwana at 6-15 p.m. the horrified Chelmsford surveyed the chaos, death and devastation and was heard to whisper: ”But I left more than 1,000 men to guard the camp!”

The 1,329 British dead included 52 officers and 806 non-commissioned officers and men, while the Zulu toll was also in excess of 1,000.

At dawn next day, after sleeping fitfully among the blood and entrails in the pillaged camp, Chelmsford marched his men the 10 miles to Rorke’s Drift and was visibly relieved to find that the 100-strong garrison had successfully defended the outpost against 5,000 Zulus.

Six months later, a contrite and wiser Lt.-Gen. Chelmsford formed his troops into a hollow square near Ulundi to rout the Zulus and end hostilities. He returned to England a month later and never commanded troops in the field again. On 9 April 1905, at the age of 78, he had a fatal heart attack whilst playing billiards at his London club.

Accusing fingers were pointed at Colonel Durnford for leaving the camp, but an inquiry established that he was never verbally ordered or received written instructions to take over the command from Pulleine, who also died in action.

Durnford’s remains were buried in the Fort Napier military cemetery in Pietermaritzburg on 13 October 1879 with the entire 1,500-man garrison on parade. The inscription on his headstone reads “Faithful unto Death.”

Although Isandlwana was an embarrassing and costly defeat for Great Britain, it was a tragic lesson that saved British lives in the Anglo-Zulu War’s remaining battles and so, in that sense, the heroic soldiers of the 24th Regiment did not die in vain.

By Richard Rhys Jones. The writer’s historic novel “Make the Angels Weep” is available as an e-book from Amazon Kindle.

Published: January 16, 2021.