The Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) was one of many suffrage societies in action in the beginning of the Twentieth Century. It was formed in February 1903 in the house of Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst, who had become frustrated by the lack of impact of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage.

Popular knowledge of their actions focuses on protests, sashes proclaiming ‘votes for women’, women chaining themselves to railings, hunger strikes and resultant force feedings. As such, any violence relating to the suffragette campaign is generally considered to be directed against them, rather than carried out by them.

However, the suffragette movement, in particular the militant WSPU, should be regarded as violent, a distinction which distances suffragettes from peaceful suffragists. Their ‘outrages’ – escalating to bombings, arson, and chemical attacks – caused harm to individuals, as well as to public and private property, and potentially had a detrimental effect on the outcome of the suffrage campaign.

‘They were got by hard fighting and they could have been got no other way’- Christabel Pankhurst giving a speech at the St. James’ Hall, October 1908.

For members of the WSPU, violence was justified by the perceived lawlessness of government and futility of the peaceful work of suffragists: several bills on women’s suffrage had been scheduled for debate at the turn of the century, yet they fell through due to insufficient time for debate.

Further, the favour of sympathetic MPs, Gladstone for instance, made little impact. Members of the WSPU believed militancy was the only way to catch and retain the attention of the public and parliament and force suffrage for women.

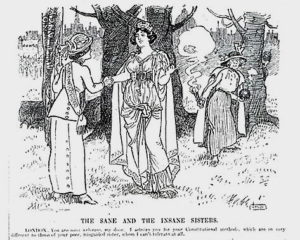

1913 cartoon, showing “Dame London” welcoming a suffragist, while behind her a suffragette holding a bomb threatens London

1913 cartoon, showing “Dame London” welcoming a suffragist, while behind her a suffragette holding a bomb threatens London

‘A suffrage army in the field’- Emmeline Pankhurst, My Own Story.

The WSPU assumed the organisation of an army. Control was centred around the Pankhursts, who managed to retain leadership even when Christabel was exiled to Paris. A small group of paid workers carried out the majority of the campaign, with volunteers playing only peripheral roles. For instance, Charlotte Marsh was involved in eight demonstrations, and Jennie Bains seven. Clearly, there was a shortage of people who were prepared to be militant, and those who did needed to be retained.

‘We must make Mr Asquith as much afraid of us as King John was of the Barons’- Christabel Pankhurst (1908) referencing the drafting of the Magna Carta.

Members of Parliament to whom the WSPU were particularly hostile were personally targeted. Prime Minister Asquith’s residence had stones thrown at its windows, and in Liverpool in 1910 two members – Selina Martin and Lesley Hall – passed themselves as orange sellers and catapulted missiles at his car.

Mary Leigh, having only removed the ear and cheek of MP John Redmond with her hatchet, missing Asquith, attempted to burn down the Theatre Royale in Dublin as Asquith attended a Matinee. Likewise at Bingley Hall in Birmingham, suffragettes dropped slates from the rooftop of a nearby building onto the crowded street, hitting Asquith’s car and police officers who were trying to arrest them.

Any visit of a government minister usually entailed a WSPU outrage: Asquith’s presence was met with an attempt on a football grandstand at Headingley in November 1913, a fire at the Rusholme Exhibition Centre and two fires in Liverpool the following month. Likewise, Lloyd George was ‘welcomed’ by a fire at a school near Sutton-in-Ashfield, and an attack of a racecourse in Stockton-on-Tees.

‘We deliberately counted up the cost, even the cost of human life; and came to the conclusion that it was worth while.’- Dora Marsden in the Manchester Guardian.

The violence of the suffragettes endangered the lives of members of the public. Suffragette outrages were designed to put ‘pressure on the private citizen’ to gain the vote, as outlined in the WSPU’s seventh annual report in April 1913. The first instance of such harm was when a Battersea clerk received chemical burns while preventing a suffragette pouring chemicals over an MP’s papers. Postmen – as many as four in Dundee – suffered burns from phosphorous chemicals put in post boxes, and a bomb found in the South Eastern District Post Office could have killed the 200 employees had it exploded.

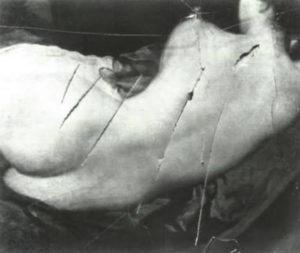

The Rokeby Venus, slashed by suffragette Mary Richardson in March 1914, because of ‘the way men visitors gaped at it all day long’

The Rokeby Venus, slashed by suffragette Mary Richardson in March 1914, because of ‘the way men visitors gaped at it all day long’

Injuries leading to death were seldom caused by suffragette actions however a Leeds police officer died from blows to the spine whilst trying to suppress a riot. The Bradford Daily Telegraph commented in response to suffragette complaints that they had been subject to police violence that ‘had the police wished to make counter complaints, several might have complained of being smacked on the face or struck by the militant ladies.’

Damage to private property and public conveniences was frequent, with a view to cause maximum inconvenience and destruction. In total there were over thirty railway related attacks, with bombs on trains and in stations, resulting in panic and disruption. Further, religious buildings were a favourite target, because of their perceived representation of the patriarchy: thirty-two churches were attacked, including St Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey. The clergy had voiced support for the suffrage movement; such a response was considered ungrateful.

The remains of the Kew Garden Teahouse, after a Suffragette arson attack in February 1913. The location was chosen due to its popularity. Source: National Archives

The remains of the Kew Garden Teahouse, after a Suffragette arson attack in February 1913. The location was chosen due to its popularity. Source: National Archives

WSPU outrages did not win them sympathy from parliament, the public nor other suffrage organisations. Upon Emmeline Pankhurst’s centralisation of leadership, several WSPU members split from the union, some, such as Charlotte Despard, Edith How Martyn and Teresa Billington-Greig, formed the Women’s Freedom League in 1907. Martyn displays their hostility to the Pankhursts’ autocratic leadership: ‘If we are fighting against the subjection of woman to man, we cannot honestly submit to the subjection of woman to woman.’

This reduced fundraising and recruitment: the WSPU could rely on just one hundred people for a sustained campaign at any one time. Other suffrage societies made a conscious effort to distance themselves from the WSPU’s outrages. From November 1909, upon attaining membership to the London Society for Women’s Suffrage, women pledged ‘to adhere to lawful and constitutional methods of agitation solely.’

The destruction caused by WSPU attacks won them the reputation of hysterical and reckless, weakening their claims to be responsible and deserving voters. Changing public attitude from tolerance to opposition, the violence kindled condemnations and calls for harsh repression of the movement, at best tinged with regret, from almost every national newspaper. Tangible evidence of the resultant obstinacy of the opposition is evident in the defeat of a bill for women’s suffrage: previously suffrage bills had secured Commons majorities, so this was a serious reversal of fortunes.

Just two days after the First World War was declared, Pankhurst committed the funds and resources of the WSPU to the war effort, suspending its militancy indefinitely. Women around the country were involved in supporting the war in munitions factories, hospitals, food production and a women’s police force.

In 1918, women over thirty who owned property worth at least £5 were given the vote. It could be argued that the threat of greater suffragette violence, especially after women’s contribution to the war effort, helped drive the reforms.

Eleanor Wallace is a student on a gap year, which she has filled with reading, online courses and work in her local bookshop. Next year she will study History at the University of Oxford.

Published: February 10, 2022.