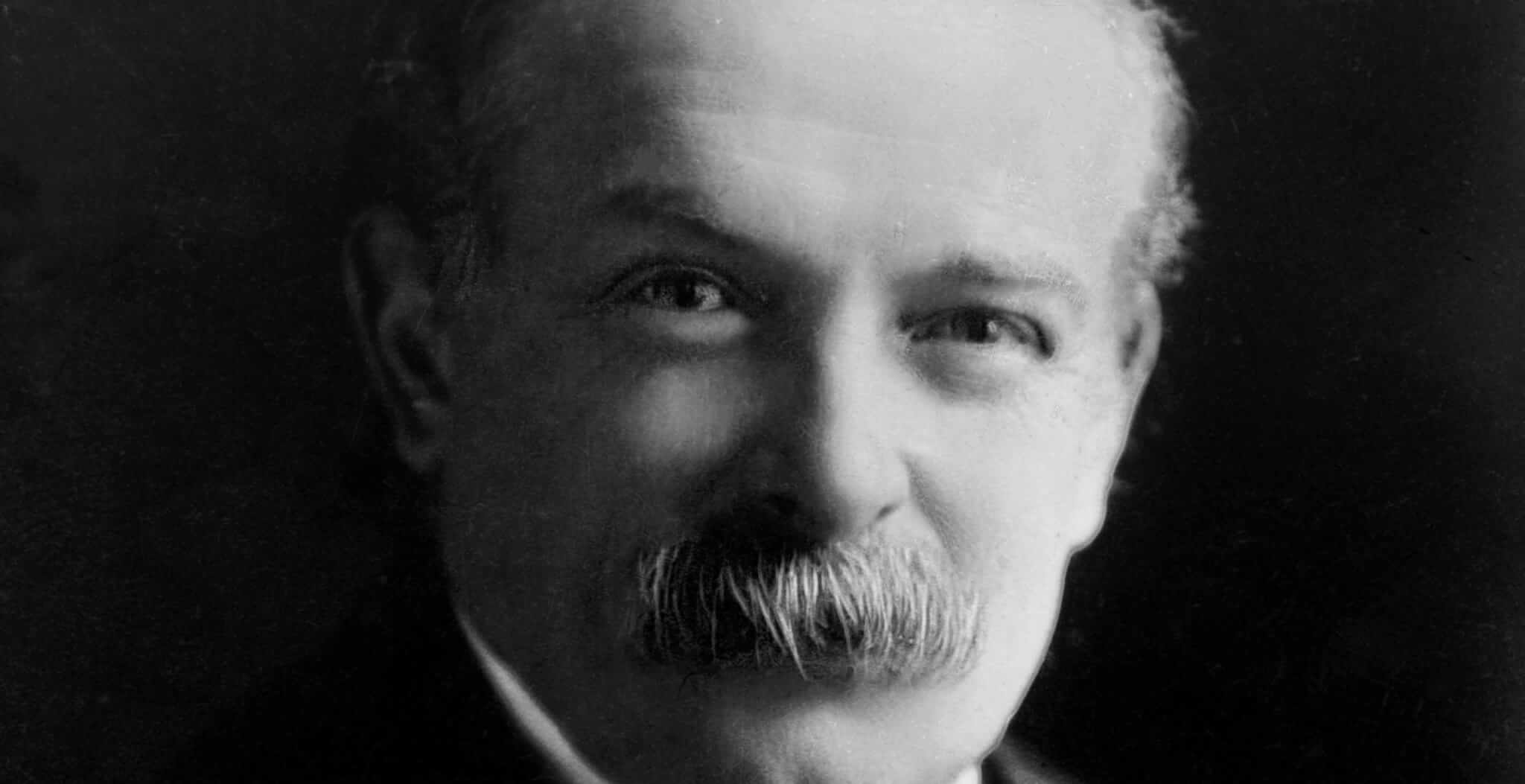

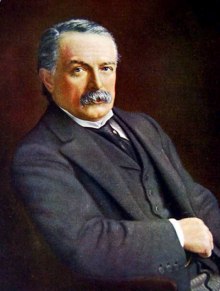

Some have called him ‘the most famous Welshman ever born in Manchester’, however it was David Lloyd George’s Welshness that so steered his career and established him as one of the most influential British politicians of the modern era, second only perhaps to Winston Churchill.

David Lloyd George was born in Manchester on 17th January, 1863. David’s father William, a schoolmaster, died a year after he was born and his mother took her two children to live with her brother in Llanystumdwy, Caernarvonshire.

Brought up in this Welsh-speaking Nonconformist family, Lloyd George identified with the upsurge of Welsh national feeling against the English dominance over Wales.

Lloyd George was an intelligent boy and did very well at his local school. After passing the Law Society examination he became a solicitor in January 1879, eventually establishing his own law practice in Criccieth, North Wales.

In 1888 Lloyd George married Margaret Owen, the daughter of a prosperous farmer.

Lloyd George joined the local Liberal Party and became an active member. A keen supporter of land reform, Lloyd George was selected as the Liberal candidate for Caernarvon in 1890. Later that year after winning a local by-election by a landslide 18 votes, at the tender age of twenty-seven Lloyd George became the youngest member of the House of Commons.

It was Lloyd George’s fiery brand of oratory that first brought him to the attention of the leaders of the Liberal Party; in particular his speeches concerning his vehement opposition to the Boer War.

Following the 1906 General Election, Lloyd George became President of the Board of Trade, and in 1908 the new Liberal Prime Minister, Henry Asquith,promoted him to the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer.

Lloyd George now had the platform from which he could launch his radical social reforms. Determined to “lift the shadow of the workhouse from the homes of the poor”, he sought to achieve this by guaranteeing an income to people who were too old to work. Lloyd George’s Old Age Pension Act, provided between 1 and 5-shillings per week to people over seventy years of age.

His next major reform was the 1911 National Insurance Act. This provided British workers with insurance against illness and unemployment. All wage-earners had to join his health scheme in which each worker made a weekly contribution, with both the employer and state adding an amount. In return for these payments, free medical attention and medicines were made available, as well as a guaranteed 7-shillings per week unemployment benefit.

Lloyd George’s political career however, looked destined for the scrap heap when in 1912 the political weekly The Eye-Witness accused Lloyd George, along with two others, of corruption. It suggested that the men had profited by buying shares with the knowledge that a rather large government contract, to build a chain of wireless communication stations, was about to be awarded to the Marconi Company. An early example of what we now call ‘insider trading’.

Lloyd George’s political career however, looked destined for the scrap heap when in 1912 the political weekly The Eye-Witness accused Lloyd George, along with two others, of corruption. It suggested that the men had profited by buying shares with the knowledge that a rather large government contract, to build a chain of wireless communication stations, was about to be awarded to the Marconi Company. An early example of what we now call ‘insider trading’.

Although a later parliamentary inquiry revealed that Lloyd George and his co-accused had profited directly from their dealings, it was decided that the men had not been guilty of corruption. It was also about this time that rumours surrounding his irregular private life began to surface.

Lloyd George’s wife Margaret had resisted moving their family to the unhealthy environs of London and had remained in north Wales. An attractive and apparently virile man, Lloyd George had great difficulty keeping his mind and hands off the capital city’s many attractions. Thanks to his friends in the press however, his little indiscretions were in the main kept out of the papers.

By the end of July 1914, it became clear that the country was on the verge of war with Germany. Despite his initial reluctance to sanction Britain’s entry into the First World War, Lloyd George a self-confessed pacifist, quickly emerged as an inspirational war time leader, first as a successful Minister of Munitions and later as Prime Minister of the Liberal-led wartime coalition.

In order to achieve the status of Prime Minister, Lloyd George upset many in his own party when he agreed to collaborate with the Conservatives to depose the previous Liberal incumbent Herbert Asquith. Now in overall charge of the war effort, Lloyd George received much of the credit for Britain’s eventual victory.

During the 1918 General Election campaign, Lloyd George promised comprehensive reforms to deal with poor education, housing, health and transport… ‘a land fit for heroes’. Although re-elected he remained dependent upon the coalition with the Conservatives, who had little intention of delivering such radical reforms.

As head of the coalition government Lloyd George began to reap the rewards, which he perhaps felt were due to the man who had won the war for his country. Corruption rumours slowly began to circulate about his selling of peerages to top up his own political ‘fund’. There was nothing new in rewarding a party benefactor with an honour or two for his charity work. Lloyd George however, appears to have taken things to a whole new level, hawking titles from a permanent office in Parliament Square.

Apparently a knighthood could be purchased for a knockdown price of £10,000, whilst a much converted hereditary peerage, such as a baronetcy, was worth a considerable amount more at £40,000 – £50,000. Business boomed; as over the next four years 1,500 knighthoods were awarded and twice as many peerages created than had been in the previous twenty years. By 1922, it is said that Lloyd George’s till had rung up more than £2,000,000.

The recipients of these awards obviously got their just rewards for their creditable services to the community, including; a CBE to a Glasgow bookmaker who also happened to have a criminal record, a baronetcy had been recommended to a gentleman who had been convicted of trading with the enemy during the war, another to a wartime tax dodger, and so the list continued.

The public outcry that followed contributed to the fall of the discredited administration, and Lloyd George was ousted from power by the Conservative members of his cabinet. He resigned in October 1922.

For the next twenty years Lloyd George continued to campaign for progressive causes, but without a political party to support him, he was never to hold power again. He died on 26th March 1945, ironically just a few weeks after being awarded a peerage himself.

Published: 12th January 2015.