Sir Henry Morton Stanley’s early life appears to have been a mix of poverty, adventure and make-believe. Stanley was actually born John Rowlands in the Welsh county town of Denbigh in 1841. His teenage mother Elisabeth Parry registered the birth of “John Rowlands, Bastard”, at St. Hilary’s Church.

Shortly after his birth, Elisabeth abandoned the care of her son to his grandfather, but unfortunately he died just a few years later and so at the tender age of six, John Rowlands Jnr. was dispatched to the workhouse at nearby St. Asaph. It was also around this time that John Rowlands Snr. is said to have died whilst working the fields; he was seventy-five.

Any parent left alive may have been just a little concerned at the reports of the day concerning the St. Asaph Workhouse, where according to one 1847 source, male adults “took part in every possible vice”. Apparently untroubled by such unsavoury goings-on, John Rowlands Jnr. appears to have received a sound education in the workhouse, developing into an avid reader.

At seventeen, John signed up as a cabin boy on board an American freighter and jumped ship shortly after it docked at New Orleans. There he invented a new identity for himself. Henry Stanley was a wealthy local cotton merchant and John took his name claiming to be his adopted son, although it is unlikely that the two ever met.

Under his new name, Stanley joined the Confederate Army following the outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 and fought at the Battle of Shiloh. After being captured he quickly changed sides and enlisted in the Union Army. Perhaps preferring a life at sea he appears to have deserted the Union Army and joined the Federal Navy serving as a clerk on board the frigate Minnesota, before he eventually jumped that ship as well.

In the years that followed, Stanley toured the American Wild West, working as a freelance journalist, covering the many battles and skirmishes with the Native American Indians. He also went to Turkey and Asia Minor as a newspaper correspondent reporting on Lord Napier’s British military foray into Abyssinia.

Although Stanley had become a special correspondent for the New York Herald some years earlier, it was not until October 1869 that Stanley received his orders from the then editor of the paper, James Gordon Bennett, to ‘Find Livingstone’. Nothing had been heard of the great Scottish missionary-explorer for almost a year, when he was reported to be somewhere near Lake Tanganyika.

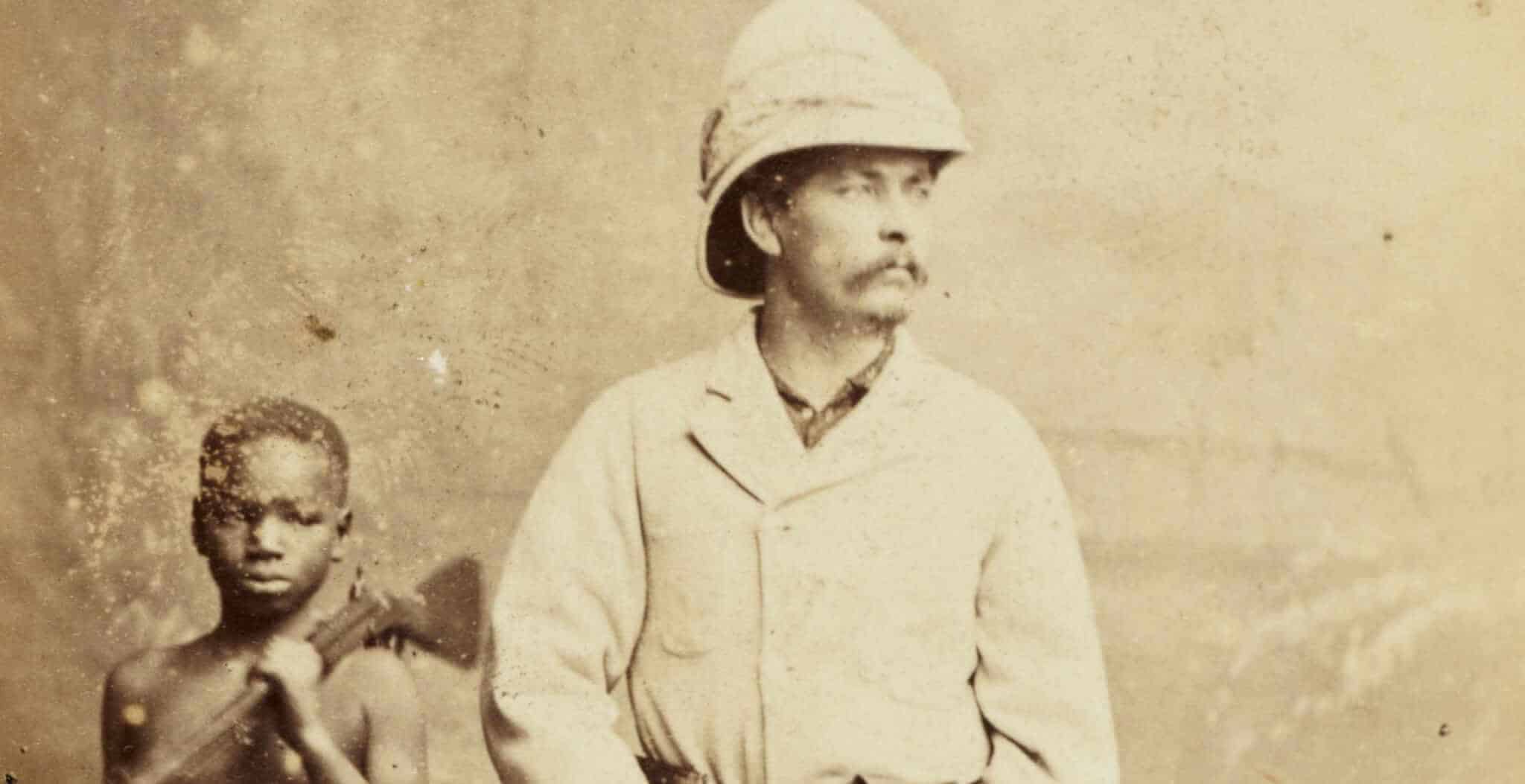

Setting off on his quest, Stanley first stopped at Egypt to report on the opening of the Suez Canal. Travelling through Palestine, Turkey and India he eventually arrived on the east coast of Africa near Zanzibar. In March 1871, decked out in dazzling white flannels and mounted atop a thoroughbred stallion Stanley set out on his 700 mile overland trek. A small army of guards and bearers brought up the rear.

The trials associated with African travel soon became obvious as only days into the adventure Stanley’s stallion died, the result of a tsetse fly bite. Vital supplies were lost as native bearers deserted the expedition and for those that stayed, a host of exotic diseases took a heavy toll. Tribes of warring natives showered the unwelcome visitors with spears and poisoned arrows. One set of flesh-hungry warriors even pursued the expedition shouting “niama, niama” (meat, meat), a tasty dish apparently when boiled and served with rice!

Stanley’s expedition travelled 700 miles in 236 days, before finally locating an ailing David Livingstone on the island of Ujiji near Lake Tanganyika on 10th November 1871. On first meeting his hero Livingstone, Stanley apparently tried to hide his enthusiasm by uttering his now famous, aloof greeting: “Doctor Livingstone, I presume”.

Together Livingstone and Stanley explored the northern end of Lake Tangayika but Livingstone, who had been travelling extensively throughout Africa since 1840, was now suffering the ill-effects. Livingstone eventually died in 1873 on the shores of Lake Bagweulu. His body was shipped back to England and buried in Westminster Abbey – Stanley was one of the pall-bearers.

Stanley decided to continue Livingstone’s research on the Congo and Nile river systems and started his second African expedition in 1874. He journeyed into central Africa circumnavigating Victoria Nyanza, proving it to be the second-largest freshwater lake in the world, and discovered the Shimeeyu River. After sailing down the Livingstone (Congo) River, he reached the Atlantic Ocean on 12th August 1877. Stanley’s three white travelling companions, Frederick Barker, Francis and Edward Pocock, along with expedition’s dogs from Battersea Dogs’ Home, all died during the gruelling 7,000-mile long trek.

It was following this expedition that King Leopold II of Belgium employed Stanley to “prove that the Congo basin was rich enough to repay exploitation”. Stanley returned to the area establishing the trading stations that would ultimately lead to the founding of the Congo Free State in 1885. Leopold’s exploitation of the country’s natural resources was dubbed “the rubber atrocities” by the international community of the time.

It was Stanley’s third and last great African adventure of 1887-89 that was the subject of much controversy, when one member of the expedition bought an 11-year-old native girl for the price of a few handkerchiefs. James Jameson, the heir to an Irish whiskey empire, gifted the girl to a tribe of local cannibals so he could watch her being dismembered, cooked and eaten, while he recorded the events in his sketch book. Stanley was sickened and furious when he eventually found out what had happened, by which time Jameson had already died of fever. He said of Jameson that he may not have been “originally wicked”, however Africa and its horrors had dehumanised him.

By 1890 Stanley had settled in England, although he did spend months in both the United States and Australia on lecture tours. Following his knighthood in 1899, Stanley sat as a Unionist MP for Lambeth from 1895 to 1900. He died in London on 10th May 1904.

Stanley was considered the most effective explorer of his day, and it was he who undoubtedly paved the way for colonial rule throughout the areas he explored and charted. Stanley’s publications include his diary, How I found Livingstone, and his account of his journey to the sources of the Nile, Through the Dark Continent (1878). In Darkest Africa (1890) is the story of Stanley’s 1887-89 expedition.

Published: 10th January 2015.