John Lackland, John Softsword, the phoney king… Not names one would want to be known by, especially as a monarch ruling over lands that stretched from Scotland to France. King John I has a negative historiography, perhaps only surpassed by that of ‘Bloody’ Mary, her history being penned by the contemporaries of Foxe’s ‘Book of Martyrs’ and Puritan England.

Why then is he remembered in such a disrespectful manner? He is the founder of our modern record keeping system for finance and also brought into being the Magna Carta, the foundation of most modern democracies. And yet in the history of the English monarchy there is only one King John.

From the outset family connections left John at a disadvantage. The youngest of five sons he was never expected to rule. However after his three eldest brothers died young, his surviving brother Richard took the throne on the death of their father Henry II.

Richard was a brave warrior and had already proven himself in battle on countless occasions. On his ascension to the throne he also took the cross and agreed to travel to the Holy Land with Philip II of France to battle Saladin in the Third Crusade. The crusade to take back Jerusalem was a challenge, unlike the first successful crusade which had taken Jerusalem and allowed the crusaders to set up Outremer (the crusader states). The Third Crusade was held in the wake of the failure of the second, alongside increasing Muslim unity in the area. His willingness to go on crusade at this point marks him out as worthy of his nickname Richard the Lionheart.

In comparison to this tall, good looking warrior, John who is reputed to have been 5ft 5 inches and much less commanding a person, seemed a lesser king. On reflection however, Richard spent less than one of his 10 years as king in England; he left no heirs, a duty of a king; and he left the Angevin empire open to attack from Philip II of France. John remained in his territory throughout his reign and defended it from attack when it was threatened by Scotland in the north and by the French in the south.

The influence of his dominant and at times unpopular mother left John open to criticism. Eleanor had influence across Europe and had been married to both Louis VII of France and after the annulment of that marriage, to Henry II of England. Although she gave him eight children over 13 years they became estranged, worsened further by her support for her sons in their attempted revolt against their father. After the revolt was quashed Eleanor was placed under confinement for sixteen years.

On the death of Henry II she was released by her son Richard. It was she who rode into Westminster to receive the oaths of fealty for Richard and she had considerable influence over the affairs of government, often signing herself Eleanor, by the grace of God, Queen of England. She controlled the upbringing of John closely and when he took the throne on the the death of Richard in 1199, her influence continued. She was chosen to negotiate truces and select suitable brides for English noblemen, an important recognition of her importance as marriage was an important tool of diplomacy.

John was not the only ruler to allow Eleanor a large degree of influence. She ruled England in Richard I’s stead when he was on crusade, and even when still in disgrace for her involvement in the attempted uprising against her husband Henry II, she accompanied him and engaged in diplomacy and discussion. And yet, her desire to keep hold of her family heritage in Aquitaine dragged John into further disputes with King Philip II of France, wars that were costly in terms of prestige, the economy and ultimately land.

John had taken over an England that had been constantly battling for control of its holdings in Northern France. King Philip II had abandoned his crusade to the Holy Land due to ill health and had engaged immediately in an attempt to win back Normandy for France. Hoping to make gains while Richard I was still in Jerusalem, Phillip continued his struggles against John between 1202 and 1214.

The Angevin empire that John had inherited included half of France, all of England and parts of Ireland and Wales. However with his losses at significant battles such as the Battle of Bouvines in 1214 John lost control of much of his continental possessions, except for Gascony in Southern Aquitaine. He was also forced to pay compensation to Phillip. His humiliation as a leader in battle, combined with the subsequent damage to the economy, proved a devastating blow to his prestige. However, the chipping away of the Angevin empire had begun under his brother Richard, who had been engaged elsewhere on crusade. However Richard is not remembered with the same venom, therefore John’s reputation must have been further damaged elsewhere.

John also suffered public humiliation when he was excommunicated by Pope Innocent III. The argument stemmed from a dispute over the appointment of the new Archbishop of Canterbury after the death of Hubert Walter in July 1205. John wanted to exercise what he saw as royal prerogative to influence the appointment of such a significant post. However Pope Innocent was part of a line of popes that had sought to centralise the power of the church and limit the lay influence over religious appointments.

Stephen Langton was consecrated by Pope Innocent in 1207, but was barred from entering England by John. John went further, seizing land that belonged to the church and taking huge revenues from this. One estimate from the time suggests that John was taking up to 14% of the Church’s annual income from England each year. Pope Innocent responded by placing an interdict on the Church in England. While baptisms and absolution for the dying were allowed, everyday services were not. In an era of absolute belief in the concept of heaven and hell, this kind of punishment was normally enough to move monarchs to acquiescence, however John was resolute. Innocent went further and excommunicated John in November 1209. If not removed, the excommunication would have damned John’s eternal soul, however it took another four years and the threat of war with France before John repented. While on the surface John’s agreement with Pope Innocent which handed over his fealty was a humiliation, in reality Pope Innocent became a staunch supporter of King John for the rest of his reign. Also, somewhat surprisingly, the debacle with the Church did not produce much national outcry. John did not face uprisings or pressure from the people or the lords of England. The barons were much more concerned with his activities in France.

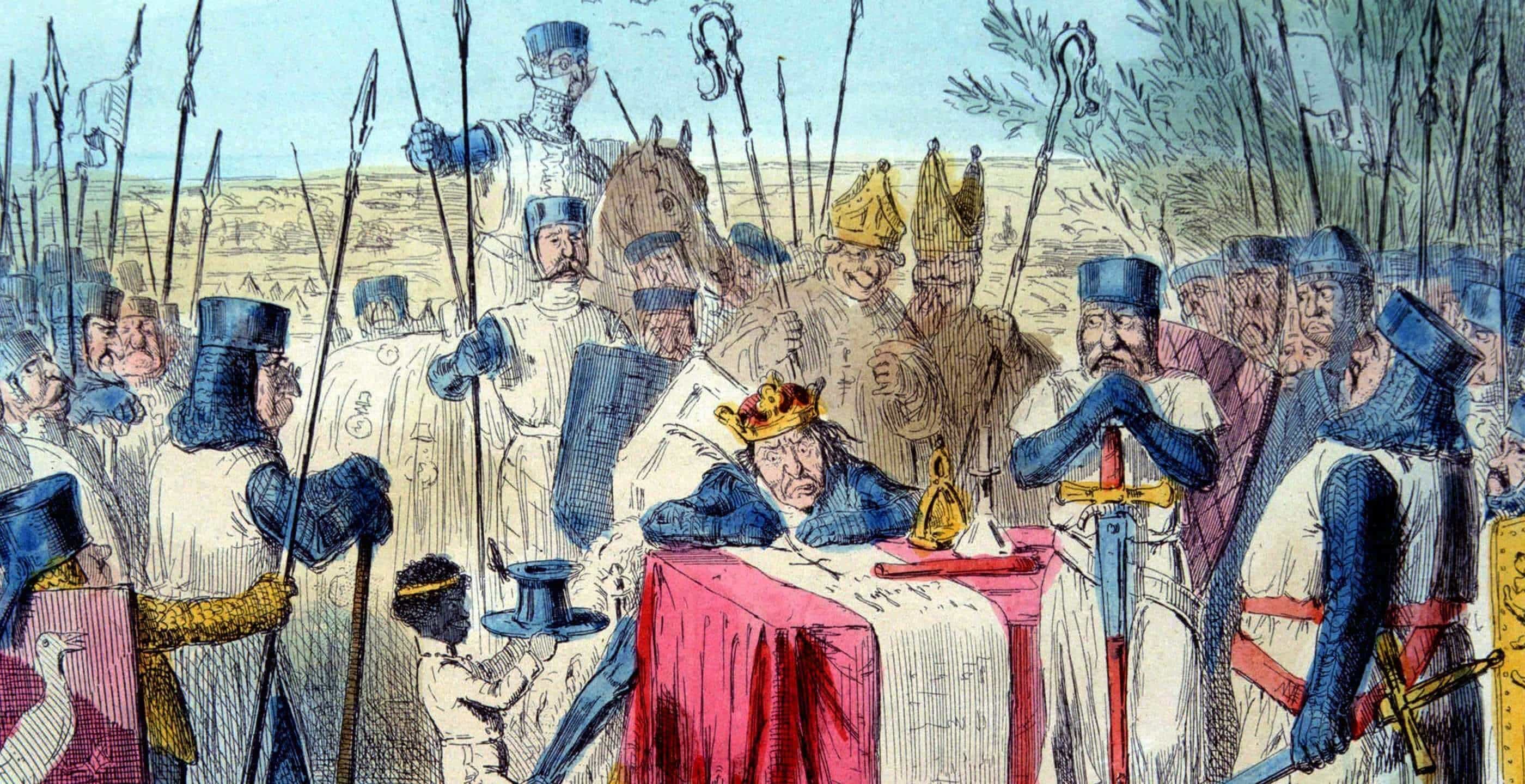

John had a tumultuous relationship with his barons, especially those in the north of the country. By 1215 many were dissatisfied with his rule and wanted him to address the issues as they saw them. In spite of support from Pope Innocent III for John, the barons raised an army and met John at Runnymede. Appointed to lead the negotiations was the Archbishop Stephen Langton, who had been ordered to support John by Pope Innocent.

John was left with no choice but to sign the Magna Carta or Great Charter. This ‘peace agreement’ did not hold and John continued to wage a near civil war within England with the First Barons War of 1215-1217. The Barons had taken London and called upon the crown prince of France, Louis to lead them. He had a claim to the English throne by marriage as he was married to Blanche of Castile, the granddaughter of Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. The rebels also had the support of Alexander II of Scotland. However, John marked himself out as a capable military leader with sieges such as that at Rochester Castle and strategically planned assaults on London. Had these successes continued, John could have settled the war with his barons, but in October 1216 John died from dysentery contracted earlier in the campaign.

John’s reign was marked by flashes of insightful and kingly behaviour. His firm dealings with Pope Innocent gained him a supporter for life, and his swift military response to the barons demonstrated a king with direction, unlike his son Henry III. The fact that he took advice from his mother, a powerhouse even towards the end of her life, perhaps shows an awareness of her political acumen. Recognising this in a woman demonstrates he was ahead of his time.

Being forced to sign the Magna Carta, which handed over many rights and freedoms to the church, the barons and freemen, has been used as a sign of weakness and yet if we look at it as a failed peace treaty, we can see it bought him time to raise his army. If we look at it as a document that enshrines basic human rights, it places him again far in advance of his time.

Smaller charges of incompetence levelled at John, such as the accusation that he lost the crown jewels, can be met with tales of his administrative skill as he streamlined the financial recording system of the day in the pipe rolls.

So, why has there only been one King John? Like Mary I, John has been remembered unkindly in the history books; the two main chroniclers Roger of Wendover and Matthew Paris, writing after his death, were not favourable. That combined with continued power of the barons resulted in many negative accounts of his reign which in turn damned his name for future kings.