We take single-sex public toilets for granted today. It is hard to believe that when public conveniences were first constructed, the vast majority of these toilets were just for men.

The story in Britain starts in 1851, as the Great Exhibition show-cased the first public flushing toilet, created by George Jennings, who was a plumber from Brighton. The popularity of this invention was such that the first public lavatories opened the following year and were known as ‘Public Waiting Rooms’. The vast majority of these were men’s conveniences.

In the mid-19th century, many areas of life were sex-segregated and gendered; the private sphere was for the women, the public sphere was for men. Whilst working-class women did undertake plenty of work, they did not own their own wages, their husbands did. The popular image of a woman was of the ‘Angel in the House’ ideal, a woman who was devoted and submissive to her husband.

In Victorian Britain, most public toilets were designed for men. Of course, this affected women’s ability to leave the home, as women who wished to travel had to plan their route to include areas where they could relieve themselves. Thus, women never travelled much further than where family and friends resided. This is often called the ‘urinary leash’, as women could only go so far as their bladders would allow them.

This lack of access to toilets impeded women’s access to public spaces as there were no women’s toilets in the work place or anywhere else in public. This led to the formation of the Ladies Sanitary Association, organised shortly after the creation of the first public flushing toilet. The Association campaigned from the 1850s onwards, through lectures and the distribution of pamphlets on the subject. They succeeded somewhat, as a few women’s toilets opened in Britain.

Then a second group emerged called the Union of Women’s Liberal and Radical Associations, which campaigned for working class women to have public toilets in Camden. In 1898 the members wrote to The Vestry in Camden for toilet access for women in the already existing men’s toilets. However, the plans for a women’s toilet were set back by several years as men opposed the women’s toilets being situated next to the men’s.

In some cases, plans for women’s toilets were deliberately sabotaged. When a model of a women’s toilet was set up on the pavement in Camden High Street, hansom cabs (driven by men) deliberately drove into the model toilet to demonstrate that it was situated in a most inconvenient position!

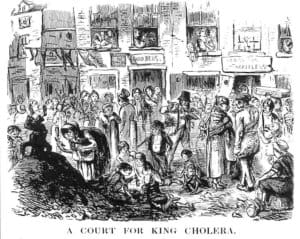

Illustration from Punch magazine, 1852

Illustration from Punch magazine, 1852

Demands for public toilets arose against the backdrop of a desire for better sanitation, which resulted in legislation being passed by Parliament in the form of two public health acts, the First Public Health Act of 1848 and the Second Public Health Act of 1875. The 1848 act was passed in the wake of a cholera outbreak that killed 52,000 people and the Act provided a framework for local authorities to follow; however it did not stipulate that the authorities had to act. The later 1875 Public Health Act allowed local authorities new powers such as being able to purchase, create and repair sewers, and to control water supplies.

However, there came a pivotal moment when women really did need to use the toilet.

Suffragettes are famous for campaigning for the right to vote but they also campaigned for the right to serve, achieved in 1915. By the end of World War One, over 700,000 to 1 million women had become ‘munitionettes’, slang for women who had gone into munition factory work to support the war effort.

However, as women were now entering previously male-dominated professions, they began to campaign for better facilities such as changing rooms and toilets. Some employers did not want to install women’s toilets, especially after the war, as they believed that women were stealing men’s employment: quite legal at the time, as there were only limited protections for workers.

Nowadays however, under the 1992 Workplace Regulations, not ensuring that men and women have separate toilet facilities is illegal for employers.

Women’s public toilets have always been somewhat political, either through moral objections, such as the Victorian ideal of a submissive, house-chained wife, or through the fact that women have campaigned for them. And the politics of women’s toilets is still present today within society: for example, UNESCO recommends single-sex toilets in order to boost women’s access to education. In Mumbai in India, there are fewer toilets for women than for men, and women must also pay more than men to use the facilities. This has led to the ‘Right to Pee’ campaign promoted by Indian feminists.

By Claudia Elphick. Claudia Elphick is a History, Literature and Culture undergraduate student at the University of Brighton.

Published: 24th August 2018