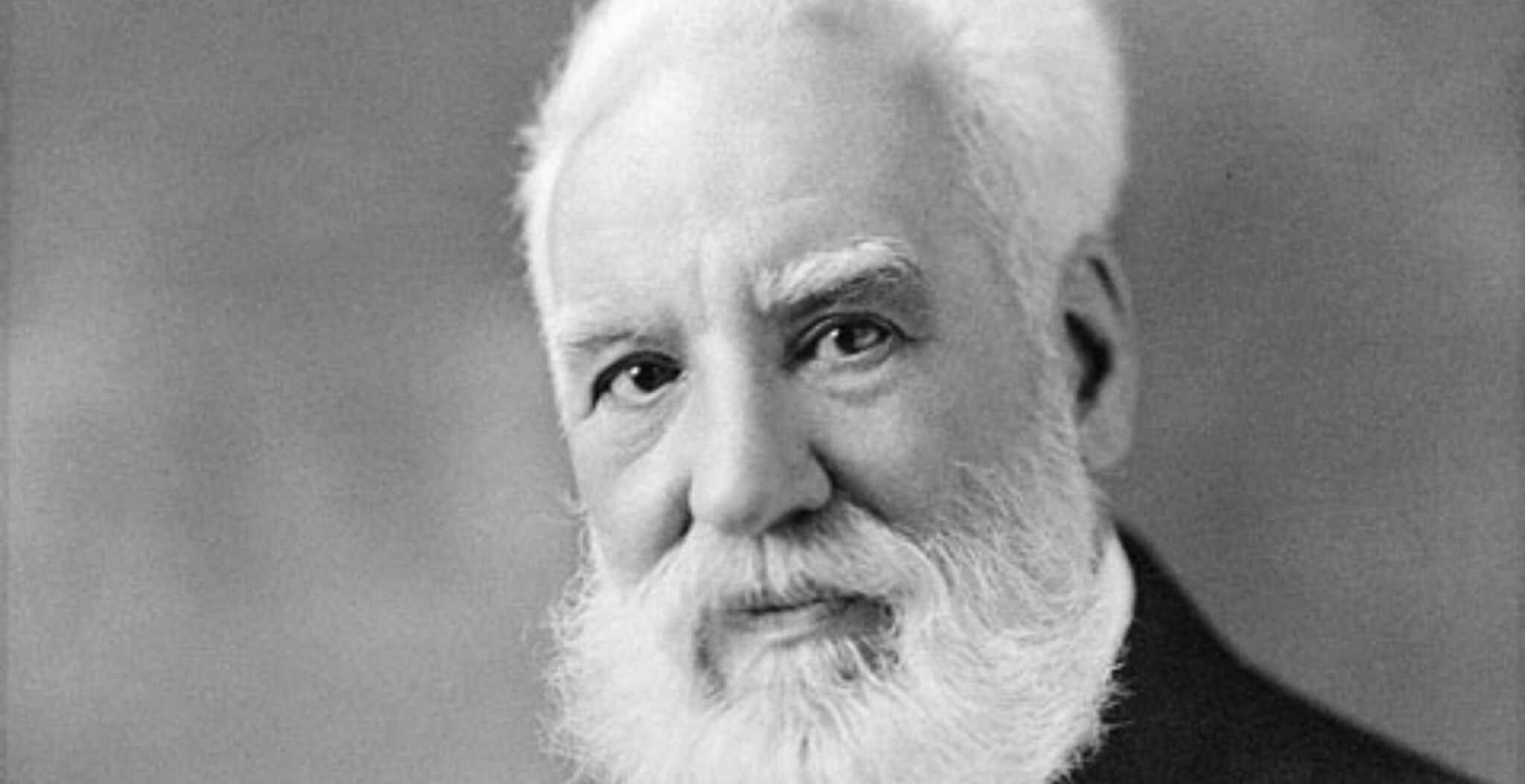

It is Queen Victoria’s husband Albert who is normally credited with being the driving force behind the Great Exhibition of 1851, but it appears that just as much praise for organising this remarkable event should also be bestowed upon one Henry Cole.

At the time Henry’s day job was as an assistant record keeper at the Public Records Office, but he had lots of other interests to including writing, editing and publishing journals. Henry’s major passions appear to have been industry and the arts, and he combined both of these as editor of the Journal of Design. The journal encouraged artists to apply their designs to everyday articles which could then be mass-produced and sold to the great unwashed.

In 1846, in his role as a council member of the Society of Arts, Henry was introduced to Prince Albert. It appears that Henry and the prince got on well as not long afterwards the society received a Royal Charter and changed its name to the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce.

With its raison d’être now clearly defined the society arranged several relatively small exhibitions to promote their cause. No doubt impressed by the much larger scale of the French ‘Industrial Exposition’ of 1844, Henry sought Prince Albert’s support to stage a similar event in England.

Initially there was little interest in the concept of an exhibition by the government of the day; undeterred by this Henry and Albert continued to develop their idea. They wanted it to be for All Nations, the greatest collection of art in industry, ‘for the purpose of exhibition of competition and encouragement’, and most significantly it was to be self-financing.

Under increasing public pressure the government reluctantly set up a Royal Commission to investigate the idea. Pessimism appears to have been quickly replaced by enthusiasm when somebody explained to the ‘powers that be’ the concept of a self-financing event. That now understood, national pride dictated that the exhibition must bigger and better than anything those Frenchies could organise.

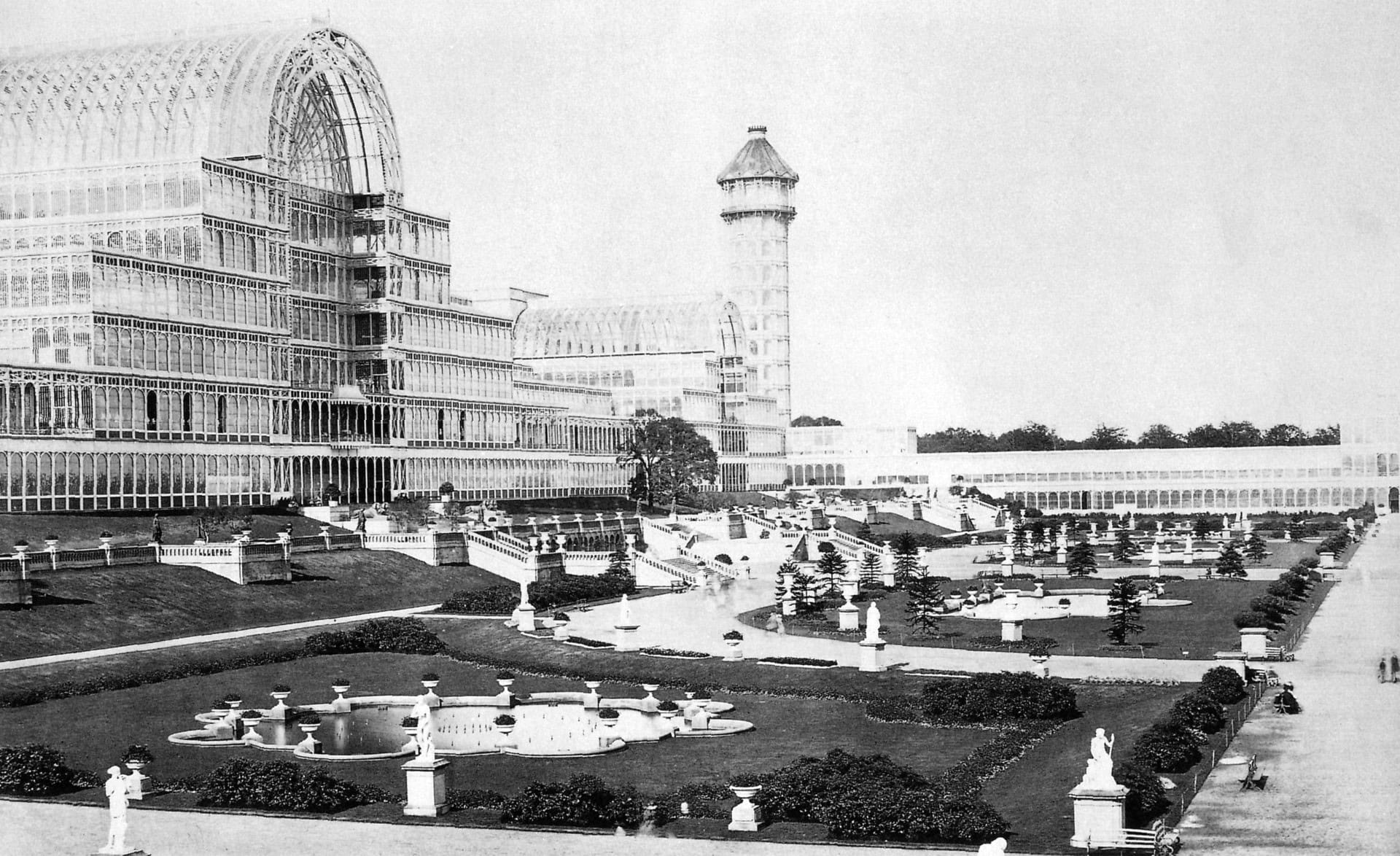

A competition was organised to design a building that would not only be large enough, but be of sufficient grandeur to house the event. The firm of Fox and Henderson eventually won the contract, submitting plans based upon a design by Joseph Paxton. Paxton’s design had been adapted from a glass and iron conservatory he had originally produced for the Duke of Devonshire’s Chatsworth House.

The issue of a suitable venue was settled when the Duke of Wellington backed the idea of Hyde Park in central London. The design of the impressive glass and iron conservatory, or Crystal Palace as it would more popularly become known, was amended to accommodate the parks rather large elm trees before building finally began.

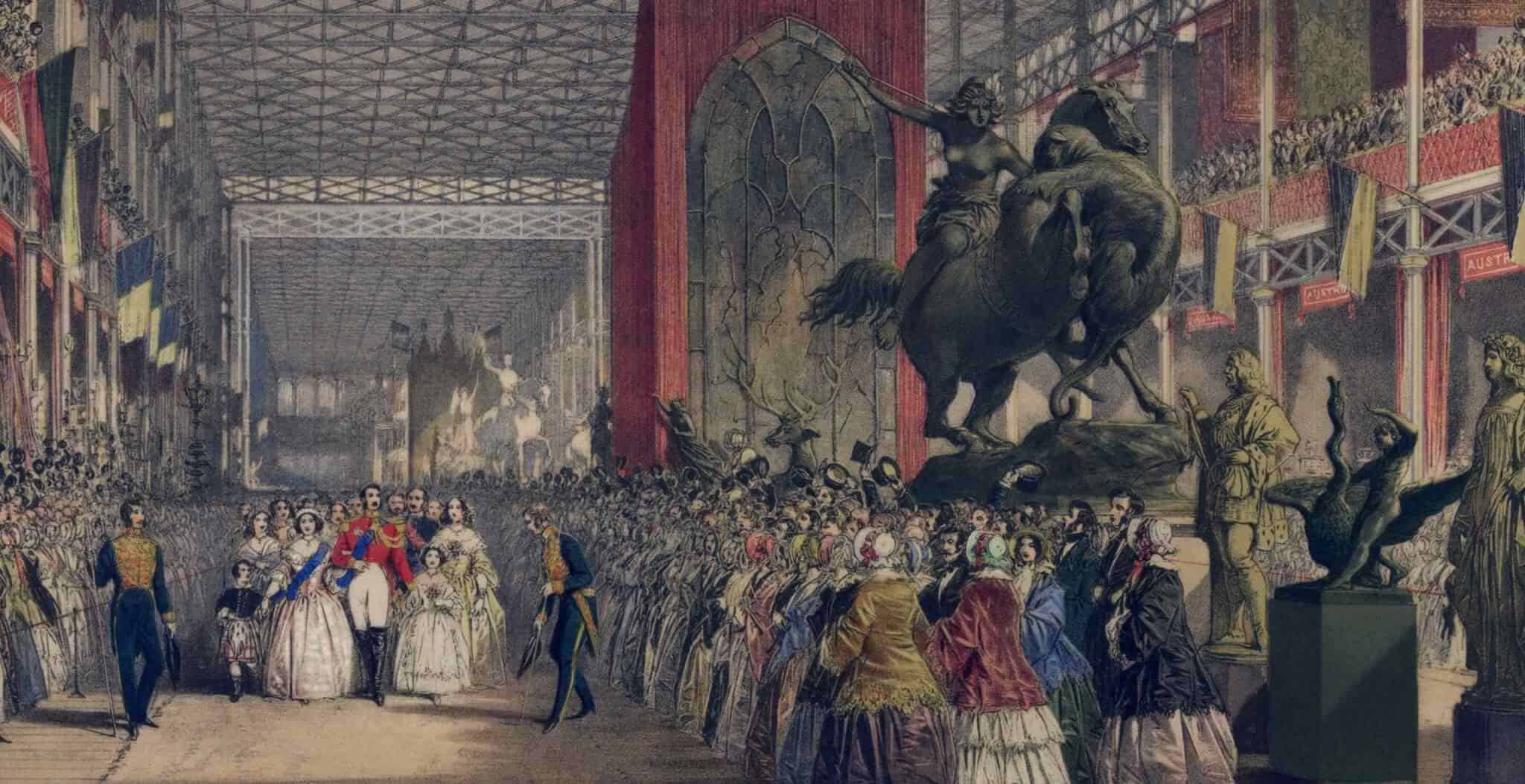

It took around 5,000 navvies to erect the 1,850 feet (564 m) long, 108 feet (33 m) high structure. But the work was completed on time and the Great Exhibition was opened by Queen Victoria on 1st May 1851.

The exhibits included almost every marvel of the Victorian age, including pottery, porcelain, ironwork, furniture, perfumes, pianos, firearms, fabrics, steam hammers, hydraulic presses and even the odd house or two.

Although the original aim of the world fair had been as a celebration of art in industry for the benefit of All Nations, in practice it appears to have been turned into more of a showcase for British manufacturing: more than half the 100,000 exhibits on display were from Britain or the British Empire.

The opening of the Great Expedition in 1851 just happened to coincide with the building of another great innovation of the Industrial Revolution. Visiting London had only just become feasible for the masses thanks to the new railway lines that had spread across the country. Church and works outings from across the country were organised to see the “Works of Industry of All Nations” all housed in Paxton’s sparkling Crystal Palace.

The Great Exhibition of 1851 ran from May to October and during this time six million people passed through those crystal doors. The event proved to be the most successful ever staged and became one of the defining points of the nineteenth century.

Not only was the event self-financing, it even turned in a small profit. Enough in fact for Henry Cole to realise his dream of a complex of museums on an estate in South Kensington which now houses the Science, Natural History and Victoria and Albert Museums, as well as the Imperial College of Science, the Royal Colleges of Art, Music and Organists and not forgetting the Albert Hall!

And what became of the Crystal Palace itself? Paxton’s clever design not only allowed the building to be quickly erected but disassembled too. And so shortly after the exhibition, the whole structure was removed from Hyde Park site and re-erected at Sydenham, then a sleepy hamlet in the Kent countryside, now a multi-ethnic part of South East London.

The future for Paxton’s Palace atop Sydenham Hill was however not a happy one. After being put to a variety of uses in the years that followed, the building was finally destroyed by fire on the 30th November 1936. The flames are said to have lit up the night sky and were visible for miles.

Sadly, the building was not adequately insured to cover the cost of rebuilding it. Very little evidence remains of this wonder of the Victorian Age except the foundations and some stonework. The memory of the glorious past survives today however, as that sleepy Kent hamlet eventually became part of Greater London and the surrounding area came to be known as Crystal Palace.

Published: 21st March 2015