One hundred years ago, on the 10th January 1918 the House of Lords gave approval for women over the age of thirty to have the right to vote. The historical political decision was passed under the Representation of the People Act. However it would not be until 1928, a decade later, that another law would be passed allowing women over the age of twenty one to vote, in accordance with male voting rights.

The issue of women’s ‘inferior’ status has plagued society throughout the centuries in British history. Indeed, in 1832 the Great Reform Act was passed, a formal acknowledgement that women did not form part of the electorate and were therefore excluded!

However the events and social changes that followed this Act would challenge and eventually dissolve this legislation but not without a great deal of hardship, struggle and animosity for those who felt it was a cause worth fighting for.

In early Victorian Britain a woman’s role had been focused solely on child-rearing and looking after the house: the idea that women were political beings entitled to an opinion let alone a vote was unheard of. However, the impact of the Industrial Revolution in Britain resulted not only in enormous economic and technological changes in the workplace, but also in a new and emerging role for women to enter the arena of public life.

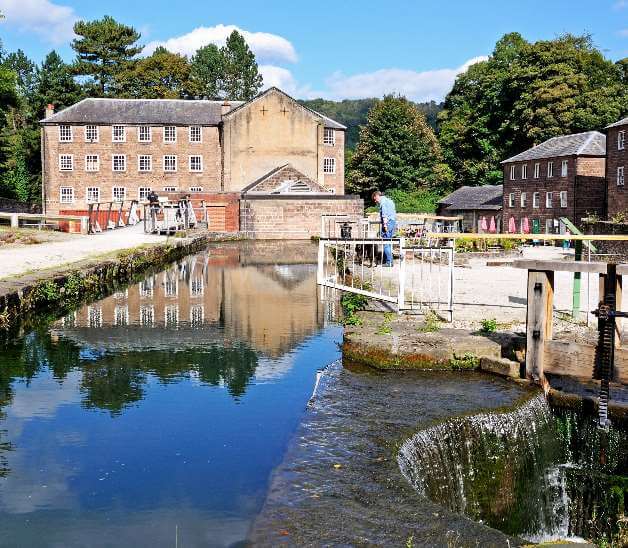

In the early 19th century the type of work a woman could find generally involved domestic service such as a cook or a maid, however now others were finding employment in industry, mainly working in factories, often in the textile industry. The famous Cromford Mill in Derbyshire was the product of the Industrial Revolution and the survival of this industry depended heavily on women.

Whilst women were working in labour-intensive roles for long hours, working under male supervision and sometimes in dangerous settings, they were also gaining their first taste of independence away from the family home. With this new independence came wider social interaction, with women free to meet and discuss larger issues such as politics and the burning social injustices of the day. Female consciousness was awakened by these new opportunities and as time went on, organisations, big and small, were set up in order to support women’s issues and rights.

In 1867, a proposal to give women the vote based on the equal rights of men was rejected in Parliament. In the years that followed, women’s suffrage campaigns and groups throughout the British Isles gained momentum. By 1872 the National Society for Women’s Suffrage was created, the first national movement with women’s rights solely in mind.

Other groups followed, so that by 1897 the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies, often shortened to NUWSS, had been formed with the support of 20 national societies. The President of the Society was the prominent feminist Millicent Fawcett who worked tirelessly on numerous campaigns for equal rights. As a suffragist Fawcett was inclined to more peaceful demonstrations and tactics whilst the suffragettes wanted militant action that would draw attention to their plight. Within the NUWSS, friction between different groups began to show and by 1903 the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) split from the main group with the desire of creating more proactive militant style of demonstration.

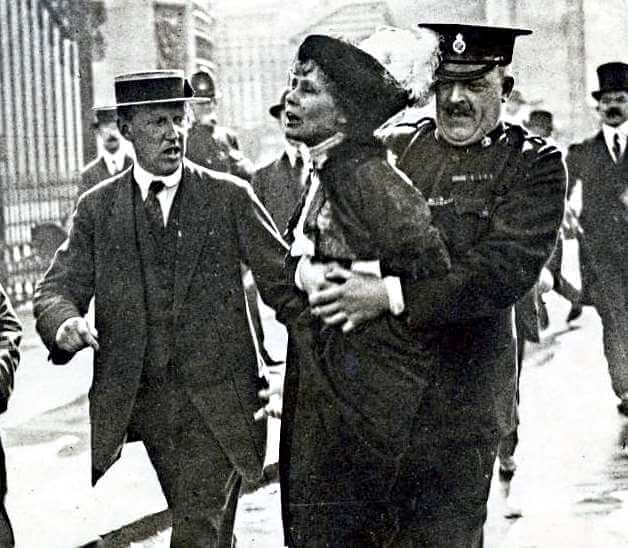

Emmeline Pankhurst and her daughters Christabel and Sylvia were leaders of the newly formed group. Unlike the NUWSS they were unelected as leaders and only women were allowed to join the organisation. The main objective they focused on was the fight for voting rights of women and they were prepared to use any tactic necessary including civil disobedience, vandalism, assault and hunger strikes.

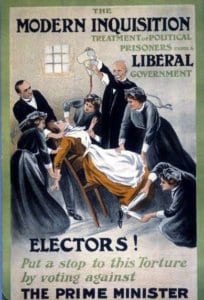

As a way of dealing with the problem of hunger strikes in prison the famous “Cat and Mouse” Act resulted in incarcerated women being temporarily released in order to prevent them from dying of hunger in prison, only to be rearrested later. The most notable display of commitment to the cause came from Emily Wilding Davison who was killed trying to attach a WSPU badge to the King’s horse at the Derby, an act that brought national recognition and awareness to the cause.

Although highlighting their cause, the actions of the suffragettes often drew criticism for their recklessness and destructiveness, particularly when in 1913 the WSPU burned down David Lloyd George’s house. This act of vandalism allowed others to make the argument that women were not capable of having such responsibilities and were uncontrollable. Furthermore, David Lloyd George had always been supportive of their cause and therefore the act seemed counter-productive to the message they were hoping to convey.

Poster by ‘A Patriot’, showing a suffragette prisoner being force-fed, 1910

Poster by ‘A Patriot’, showing a suffragette prisoner being force-fed, 1910

Others at the time were more sympathetic such as the Labour MP George Lansbury who resigned from his seat in 1912 in support of women’s enfranchisement. Meanwhile Asquith, Prime Minister from 1908 to 1916, was steadfast in his opposition to women’s suffrage and it was not until David Lloyd George replaced him as Prime Minister in 1916 that a real chance of change was possible.

The beginning of World War One in Britain altered the momentum of the campaigners. The dire realities of war meant that suffrage prisoners were released and suffragettes were urged to contribute to the war effort. Meanwhile the NUWSS continued to work on representing women and supporting gender equality whilst taking a far less volatile approach.

The First World War forced many women to take up the vacancies left by men going to fight in the war. Women found employment not only in industries such as textiles which they had previously had experience in, but also in munition factories: anything that was a necessity for the war meant that women were now essential for the everyday industries, transport and infrastructure of the country.

By 1918 women over the age of thirty had been given the right to vote, whilst the main legislation enfranchised men of twenty one years and over. For the first time, women were now regarded as capable of holding down positions in previously male-dominated workplaces. It was an undeniable breakthrough for women and all the people who campaigned so vehemently for equality. It was the first step in the right direction but there was still a lot of work to be done.

Many women who had performed so well during the war were now expected to leave their employment and return home now that the men had come back from fighting. Social attitudes were still evolving. It would not be until 1928 that another law would be passed lowering the voting age for women down to twenty one years of age in accordance with male enfranchisement.

100 years on, women’s rights remains an issue worth fighting for.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.