Margery Kempe must have cut quite a figure on the pilgrimage circuits of Medieval Europe: a married woman dressed in white, weeping incessantly, and holding court with some of the greatest religious figures of her time along the way. She leaves the tales of her life as a mystic with us in the form of her autobiography, “The Book”. This work gives us an insight into the way in which she regarded her mental anguish as a trial sent to her by God, and leaves modern readers contemplating the line between mysticism and madness.

Margery Kempe was born in Bishop’s Lynn (now known as King’s Lynn), around 1373. She came from a family of wealthy merchants, with her father an influential member of the community.

At twenty years old, she married John Kempe – another respectable inhabitant of her town; although not, in her opinion, a citizen up to the standards of her family. She fell pregnant shortly after her marriage and, after the birth of her first child, experienced a period of mental torment which culminated in a vision of Christ.

Shortly afterwards, Margery’s business endeavours failed and Margery began to turn more heavily towards religion. It was at this point she took on many of the traits that we now associate with her today – inexorable weeping, visions, and the desire to live a chaste life.

It was not until later in life – after a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, multiple arrests for heresy, and at least fourteen pregnancies – that Margery decided to write “The Book”. This is often thought of as the oldest example of an autobiography in the English language, and was indeed not written by Margery herself, but rather dictated – like most women in her time, she was illiterate.

It can be tempting for the modern reader to view Margery’s experiences through the lens of our modern understanding of mental illness, and to cast aside her experiences as those of someone suffering from “madness” in a world in which there was no way to understand this. However, this one dimensional view robs the reader of a chance to explore what religion, mysticism, and madness meant to those living in the medieval period.

Margery tells us her mental torment begins following the birth of her first child. This could indicate she suffered from postpartum psychosis – a rare but severe mental illness which first appears after the birth of a child.

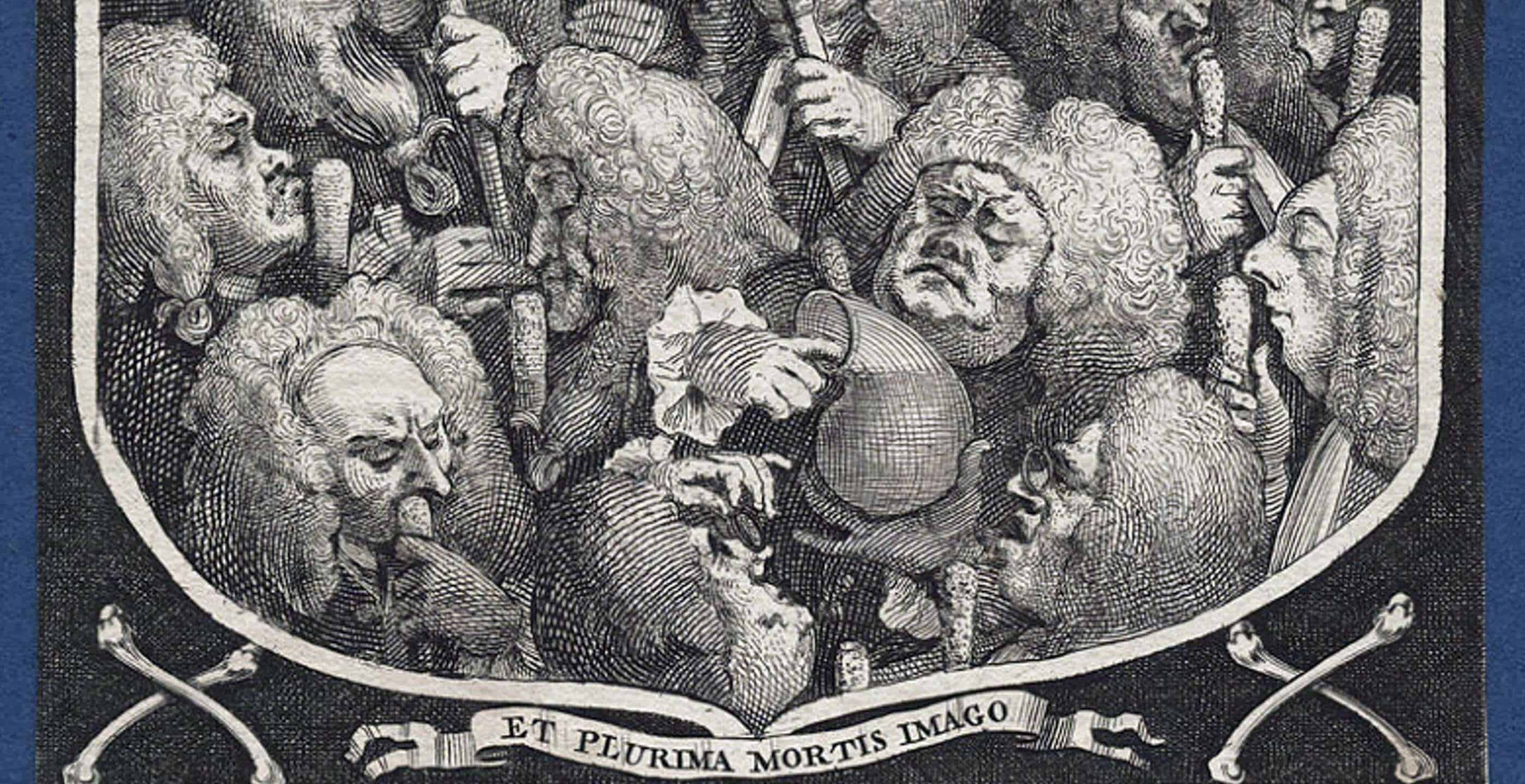

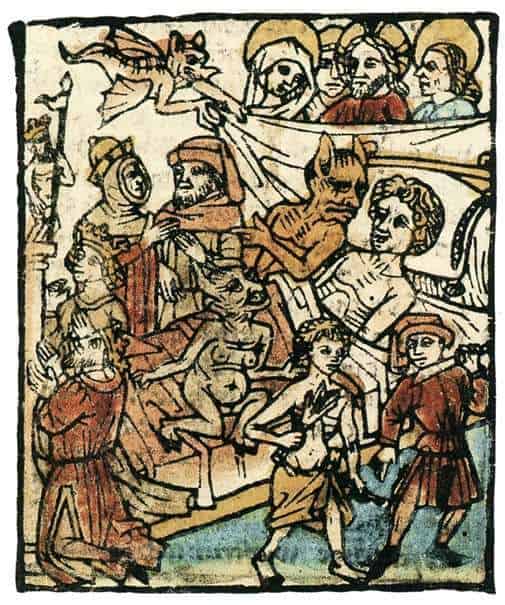

Indeed, many elements of Margery’s account match with symptoms experienced with postpartum psychosis. Margery describes terrifying visions of fire-breathing demons, who goad her to take her own life. She tells us how she rips at her flesh, leaving a lifelong scar on her wrist. She also sees Christ, who rescues her from these demons and gives her comfort. In modern times, these would be described as hallucinations – the perception of a sight, sound or smell which is not present.

Another common feature of postpartum psychosis is tearfulness. Tearfulness was one of Margery’s “trademark” features. She recounts stories of uncontrollable bouts of weeping which land her in trouble – her neighbours accuse her of crying for attention, and her weeping leads to friction with her fellow travellers during pilgrimages.

Delusions can be another symptom of postpartum psychosis. A delusion is a strongly held thought or belief which is not in keeping with a person’s social or cultural norms. Did Margery Kempe experience delusions? There can be no doubt that visions of Christ speaking to you would be considered a delusion in Western society today.

This, though, was not the case in the 14th century. Margery was one of several notable female mystics in the late medieval period. The most well-known example at the time would have been St Bridget of Sweden, a noblewoman who dedicated her life to becoming a visionary and pilgrim following the death of her husband.

Given that Margery’s experience echoed that of others in contemporary society, it is difficult to say that these were delusions – they were a belief in keeping with the social norms of the day.

Although Margery may not have been alone in her experience of mysticism, she was sufficiently unique to cause concern within the Church that she was a Lollard (an early form of proto-Protestant), although each time she had a run-in with the church she was able to convince them this was not the case. It is clear though, that a woman claiming to have had visions of Christ and embarking on pilgrimages was sufficiently unusual to arouse suspicion in clerics of the time.

For her own part, Margery spent a great deal of time worried that her visions may have been sent by demons rather than by God, seeking advice from religious figures, including Julian of Norwich (a famous anchoress of this period). However, at no point does she appear to consider that her visions may be the result of mental illness. Since mental illness in this period was often thought of as a spiritual affliction, perhaps this fear that her visions may have been demonic in origin was Margery’s way of expressing this thought.

When considering the context in which Margery would have viewed her experience of mysticism, it is vital to remember the role of the Church in medieval society. The establishment of the medieval church was powerful to an extent almost incomprehensible to the modern reader. Priests and other religious figures held authority equitable to temporal lords and so, if priests were convinced Margery’s visions came from God, this would have been viewed as an undeniable fact.

Further to this, in the medieval period there was a strong belief that God was a direct force on everyday life – for example, when the plague first fell on the shores of England it was generally accepted by society that this was God’s will. By contrast, when Spanish influenza swept Europe in 1918 “Germ Theory” was used to explain the spread of disease, in place of a spiritual explanation. It is very possible that Margery genuinely never considered that these visions were anything other than a religious experience.

Margery’s book is a fascinating read for many reasons. It allows the reader an intimate glimpse into the everyday life of an “ordinary” woman of this time – ordinary insofar as Margery was not born into nobility. It can be rare to hear a woman’s voice in this time period, but Margery’s own words come through loud and clear, written though they were by another’s hand. The writing is also unselfconscious and brutally honest, leading the reader to feel intimately involved in Margery’s story.

However, the book can be problematic for modern readers to understand. It can be very difficult to take a step away from our modern perceptions of mental health and to immerse ourselves in the medieval experience of unquestioning acceptance of mysticism.

In the end, over six hundred years after Margery first documented her life, it does not really matter what the real cause of Margery’s experience was. What matters is the way she, and the society around her, interpreted her experience, and the way this can aid the modern reader’s understanding of perceptions of religion and health in this period.

By Lucy Johnston, a doctor working in Glasgow. I have a special interest in history and historical interpretations of illness, particularly in the medieval period.