In Early Modern England*, death was viewed indelibly through the analogue of Christianity. The deathbed was a spiritual drama, a battle for the dying individual’s soul between the forces of God and the demons of Satan. If the individual died well, peacefully, with family and priest, then salvation was assumed to be theirs. A bad death, alone or in agony or without a holy man’s sacrament, was to be avoided at all cost.

There were many things an individual could do to ensure a good death. If the death had a didactic message and supplied a moral lesson, then God’s grace was thought to be that much closer. William Stout, a yeoman farmer who passed in 1681, on his deathbed exhorted his family to live in fear of god, in obedience to their mother, and in brotherness to each other; Francis Nicholson, noose around his neck in 1686, warned all children in the watching crowd at Tyburn to mind their duty to God and publicly lamented his sins. Even the condemned sought as good a death as possible.

A charitable action of some kind was expected of a good death, too. The will not only settled the dying’s earthly affairs but also, they hoped, demonstrated a Christ-like giving to others more in need. When in late June 1670 Robert Moore of the Isle of Wight drew up his will, his brother was quick to remind him to give to the poor in some way after his death, and so the document was amended. During funerals, also, alms were expected. The receiving poor would pray then for the deceased, with such ‘honest poor’ prayers, in pre-Reformation times, being thought as an especially efficacious way of speeding the soul through purgatory. A charitable will supplemented the good death, acting in a sense as a ‘passport to heaven’.

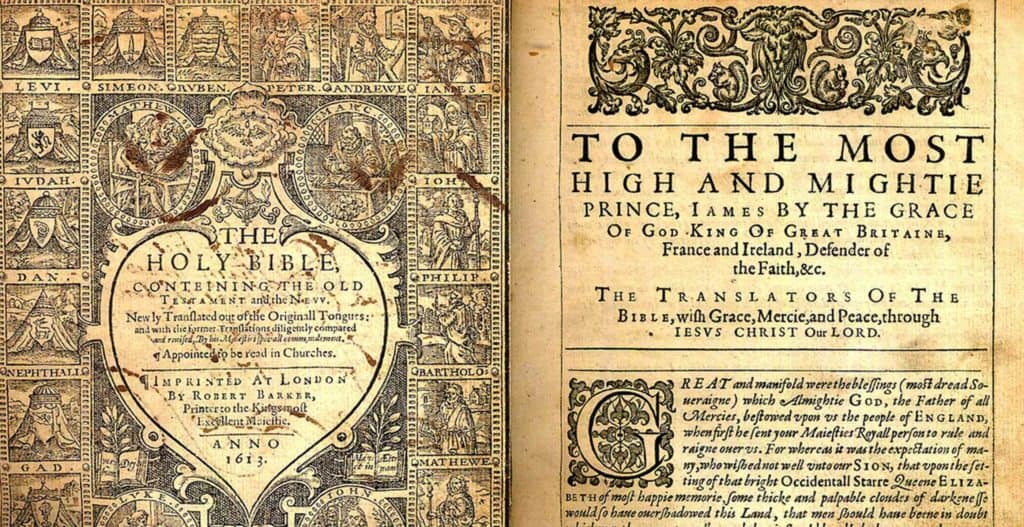

When the Protestant Reformation removed the sacramental weight from dying and made it more about the individual (holy water, confession, extreme unction, and absolution were all abolished in 1552), the good death was given even more attention.

In 1601, Christopher Sutton produced the best-selling book Learn to Die, and John Wesley’s Arminian Magazine published many a deathbed scene, disseminating what was viewed as a good death to a national readership. Dying well became an art to be learnt – the deathbed, though still the last great trial, had gone designer.

A good death had to have a watching crowd, strengthening its already theatrical nature. This allowed women of the pre-modern era a degree of agency usually not granted in religious ceremony. Disallowed, for the most part, to speak in church, the deathbed supplied women with the chance to express their spirituality in a very vocal fashion. One such example of this comes from the accounted death of Elizabeth Heywood, who in 1661, gave a deathbed speech so verbose and unlike her usual self that her father reasoned the Holy Spirit had been acting through her!

Naturally, to achieve the much coveted good death, the pitfalls of a bad death had to be avoided.

A painful, extended death by disease was not good, and only if the dying could bravely face this agony without complaint could the type of death be reversed to a good one. Delirium, too, would ruin a deathbed performance; dying loud, scared, and vocal did not square with the Last Judgement narrative of falling asleep into the next life. Delirium on the deathbed also conjured ideas of demonic possession, which was a sure sign which way the departing soul was travelling.

A sudden death, without expectation or even the chance of a deathbed performance, was also seen to have the markings of a bad death. This was, obviously, a frustrating and near impossible pitfall to avoid. Pre-Reformation at least, the sudden death was thought of poorly because it did not allow the chance for confession and any other Christian sacrament to be administered. Only with the waning of Catholic influence and the growth of secularisation did this become less of an issue.

For the early-modern Christians of Britain, suicide was the ultimate bad death. Associated with devilry and a repudiation of scripture, a person found guilty of suicide was considered a felon, and was buried at a crossroads (to stop the spirit returning to its place of death), face down, with a stake through the heart and without a proper funeral. This Felo de se (felon of himself, in Latin) process was ended with the 1823 Burial of Suicide Act, when public opinion on suicide began to lose its hard-line Christian edges.

Though desire for a good death continues even to this day, the Britons of early-modern England did gradually begin to lose their obsession.

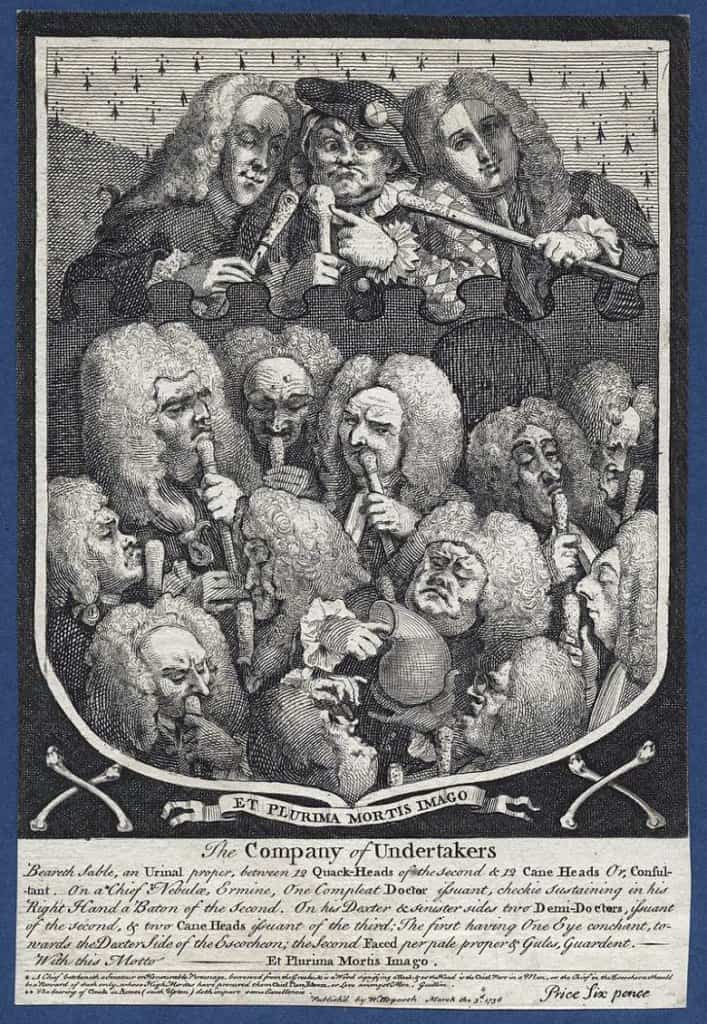

A holy living – a good life – began to take precedence over dying well, with the widely popular Holy Dying and Holy Living, published in 1650, marking this volte-face. The people of the seventeenth-century began to use the life of a person, not their death, to determine whether an individual would receive God’s salvation. Sudden deaths, as one Presbyterian Minister in 1720 noted, were now viewed as a gift from God, a prevention of needless suffering; and doctors, once thought as meddlers at the deathbed, were now commonplace and very much wanted.

Into the modern period the notion of a good death failed to keep its hold over the people of Britain. Naturally, most desired a peaceful and painless passing, but the performative aspect was lost and Christianity’s role at the deathbed diminished. The Early Modern battle for a good death tells us much about the people’s collective beliefs, fears, and indeed lives. And, of course, it tells us about death.

By Sam Dawson.Sam Dawson is a History graduate turned freelance writer based in the East Midlands.

* roughly corresponding to the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries