‘Uneasy is the head that wears the Crown’, Shakespeare, King Henry IV, Part 2.*

Especially when that head is teeming with head lice, as Adam of Usk reported when he attended King Henry IV’s coronation on 13th October 1399!

King Henry’s affliction was commonplace in medieval times, and lice were certainly no respecter of social status.

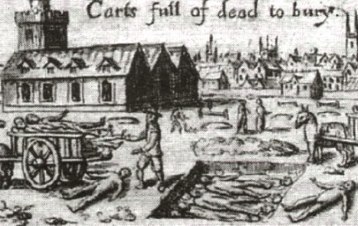

Filth was a fact of life for all classes in the Middle Ages. Towns and cities were filthy, the streets open sewers; there was no running water and knowledge of hygiene was non-existent. Dung, garbage and animal carcasses were thrown into rivers and ditches, poisoning the water and the neighbouring areas. Fleas, rats and mice flourished in these conditions. Indeed this was the perfect environment for the spread of infectious disease and plague: the Black Death was to kill over half of England’s population between 1348 and 1350.

As there was no knowledge of germs or how diseases spread in the Middle Ages, the Church explained away illness as ‘divine retribution’ for leading a sinful life.

Common diseases in the Middle Ages included dysentery (‘the flux’), tuberculosis, arthritis and ‘sweating sickness’ (probably influenza). Infant mortality was high and childbirth was risky for both mother and child.

Rushes and grasses used as floor coverings presented a very real hygiene problem. Whilst the top layer might be replaced, the base level was often left to fester.

A lack of hygiene amongst medieval people led to horrific skin complaints. Poor people washed in cold water, without soap, so this did little to prevent infection. The more disfiguring skin diseases were generally classed as leprosy and indeed leprosy, caused by the bacterium mycobacterium leprae, can arise from dirty conditions. It attacks and destroys the extremities of the body, particularly the toes and fingers, and sometimes the nose. (Pictured right: Richard of Wallingford, Abbot of St Albans; his face is disfigured by leprosy.)

A lack of hygiene amongst medieval people led to horrific skin complaints. Poor people washed in cold water, without soap, so this did little to prevent infection. The more disfiguring skin diseases were generally classed as leprosy and indeed leprosy, caused by the bacterium mycobacterium leprae, can arise from dirty conditions. It attacks and destroys the extremities of the body, particularly the toes and fingers, and sometimes the nose. (Pictured right: Richard of Wallingford, Abbot of St Albans; his face is disfigured by leprosy.)

Leprosy was not the only disease that could affect someone in this way: the affliction known as St Anthony’s Fire could also lead to gangrene and convulsions. This condition was caused by a fungus, ergot, that grows on rye. When the grain was ground to make bread, people who ate the bread became poisoned.

Sexually transmitted diseases such as syphilis were common among all social classes. Symptoms included unsightly skin rashes, recurring bouts of fever, blindness, mental illness and ultimately, death.

Whilst the poor had to make do with traditional herbal remedies and superstition to cure their ailments, the rich could afford to pay physicians.

Employing a physician did not however ensure that the patient would recover. The success of any treatment was largely down to luck; indeed, many of the ’cures’ appear quite bizarre to us today.

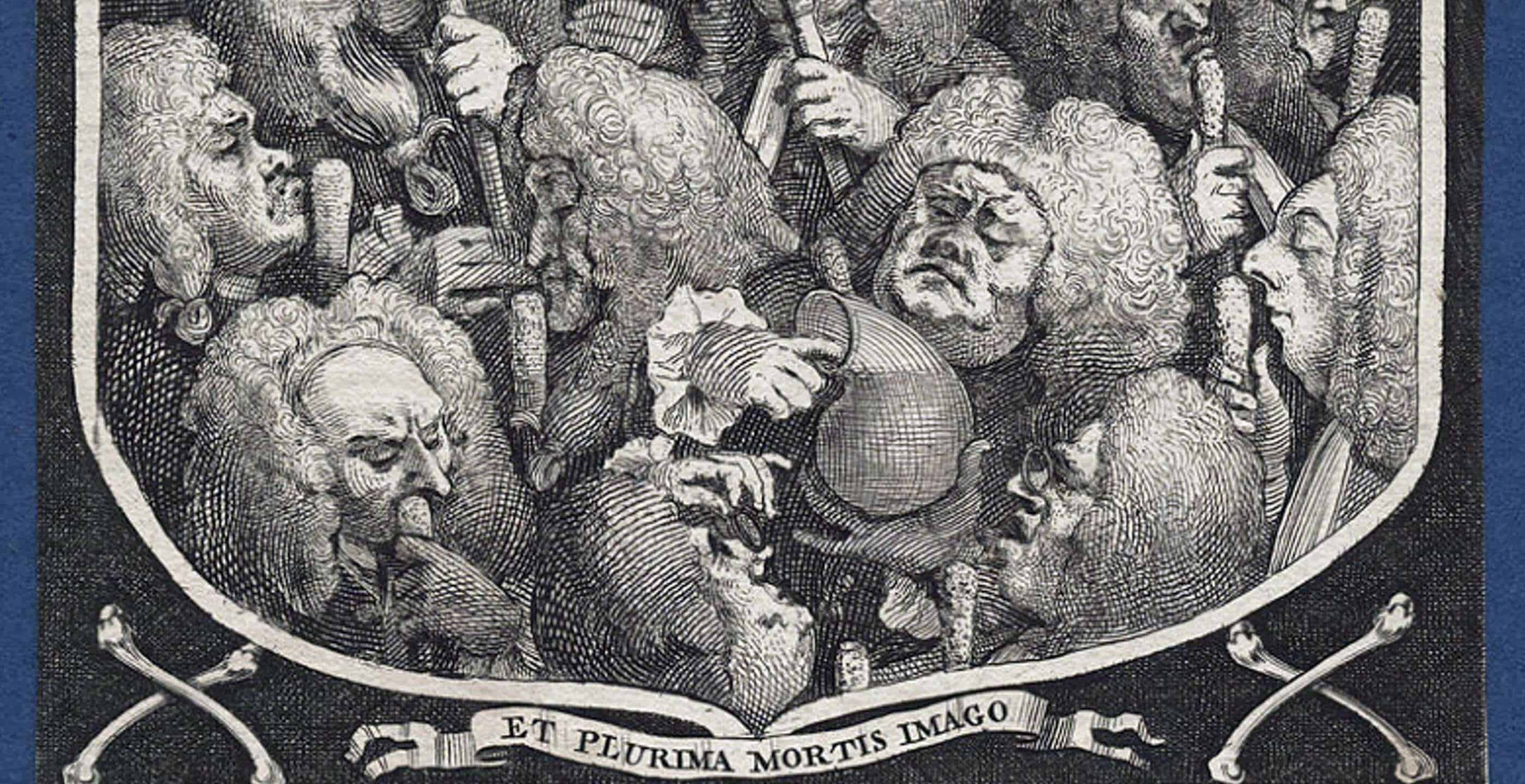

It was quite widely believed that the body had four ‘humours’ and if these became unbalanced, you became ill. A patient’s urine was used to determine whether there was indeed an unbalance. Bleeding (with or without leeches), sweating and induced vomiting were the remedies of choice to re-balance the humours.

Even the princely sport of jousting was not without its dangers – and not just broken limbs. For example, King Henry IV is believed to have suffered from seizures, perhaps as a consequence of repeated blows to the head received whilst jousting in his youth.

Crusading could also be bad for your health: wounds, infections, disease and broken bones were just some of the hazards to be faced in the Holy Land.

Should an unfortunate patient require an operation or amputation, this would be carried out by a ‘surgeon’, often a butcher or barber by trade, and would be performed without anesthetic. As the instruments were not sterilized, post-operative infections were often fatal.

A reminder of the horrors of medieval surgery survives to this day: the red and white barber’s pole traditionally found outside a barber’s shop dates back to the Middle Ages. Its red stripe represents the blood spilled and the white stripe, the bandages used during an operation.

*At this point in Shakespeare’s play Henry IV, unwell, facing rebellion and with all the responsibilities of kingship, is feeling the insecurities of his crown.