Edward Jenner was born on 17th May 1749, an English physician who would go on to be become one of the most influential scientists of all time. A pioneer of the smallpox vaccine, his work would go on to save countless lives; it is not hard to see why he is often referred to as “the father of immunology”.

He began his life in Gloucestershire, the son of local Reverend Stephen Jenner and the eighth of nine children. He went to school in Wotton-under-Edge and benefited from a strong education, being taught all the necessary basics. He would spend much of his childhood in the rural surroundings of Berkeley before leaving to train as a surgeon in London.

Whilst he was still very young he received a treatment against smallpox. This was an inoculation also known as a variolation, whereby samples are taken from infected patients, with the desire that a mild infection would provide future protection. This had a long-term impact on Jenner.

At the age of fourteen, his career looked promising when he joined Daniel Ludlow, a surgeon from Gloucestershire as an apprentice. This provided young Jenner with valuable experience, serving seven years and gaining much knowledge and expertise. One of the most important experiences Jenner had whilst working as an apprentice, was on one particular occasion, when he overheard from a local milkmaid that she was now safe from smallpox because she had already had cowpox. This remark intrigued Jenner, who would go on to study in London and still recall the words of the young milkmaid.

In 1770, Jenner went up to London, completing his training at St George’s Hospital where he was fortunate enough to be under the tutelage of the esteemed surgeon, John Hunter. It was under his guidance and with a new era characterised by the ideals of the Enlightenment age, that Hunter reportedly instructed Jenner, “Don’t think, try” and this is what he would do.

The surgeon Hunter would continue to be influential in Jenner’s life, as they remained in contact on issues regarding science and natural history and he was responsible for putting Jenner’s name forward for the Royal Society.

He was however destined to be, first and foremost, an English country doctor, choosing to return to his roots and set up practice in Berkeley where he quickly became a successful local family doctor.

Whilst he continued his work as a doctor he would meet up with surgeons and like-minded individuals to form the Gloucestershire Medical Society who would regularly meet to discuss issues of medicine at the Fleece Inn in Rodborough.

This informal group would discuss issues and share ideas with one another over dinner, reading and publishing papers on a wide variety of matters. Jenner would also partake in similar meetings with another society at Alveston, close to Bristol. During this time Jenner made valuable contributions to a variety of medical papers.

Jenner would continue to work amongst the rural and farming communities, even turning down the opportunity to work as a naturalist with Captain James Cook’s Second Expedition. He felt most comfortable in his own surroundings in Gloucestershire where he would continue to expand his knowledge on a variety of matters through observation and experimentation.

In his free time he began to research cuckoos and after many hours of observation as well as dissection, he came to the conclusion that it is the young newly-hatched cuckoo that pushes the eggs out of the host’s nest, a theory that went against the traditional belief at the time that the adult cuckoo was responsible. In fact, through his scientific investigations, Jenner was able to demonstrate how the young cuckoo had an anatomical adaptation in its back that allowed it to remove the eggs from the nest, an adaptation that would not remain past the twelfth day of its life.

Jenner’s observations of the cuckoo would end up being published by the Royal Society in 1788, where he would subsequently be elected a fellow. In the same year he married Catherine Kingscote with whom he would go on to have three children during their marriage. Sadly, his wife Catherine passed away in 1815 as a result of tuberculosis.

Back in his medical life, Jenner continued to embrace his passion for zoology, an interest which would serve him well as he would continue to investigate how a better understanding of animal biology could impact on human understanding of disease and how it is transmitted. The connections made by Jenner relating to cowpox and smallpox would also impact the creation of later vaccinations up to the present-day.

Jenner had always remembered the milkmaid who claimed immunity from smallpox, something he would scrutinise further. As his work found him largely surrounded by country farming people, he had repeatedly heard this claim of immunity whilst also noticing that many milkmaids would be clear from the unfortunate pox-ridden complexions suffered by others. The common denominator proved to be the cowpox, which whilst working with cattle proved fairly unavoidable to catch. Jenner’s theory that he wanted to prove was therefore that cowpox somehow produced a level of immunity against smallpox, a hypothesis backed by local folk who told Jenner of their attempts to deliberately infect themselves to avoid smallpox.

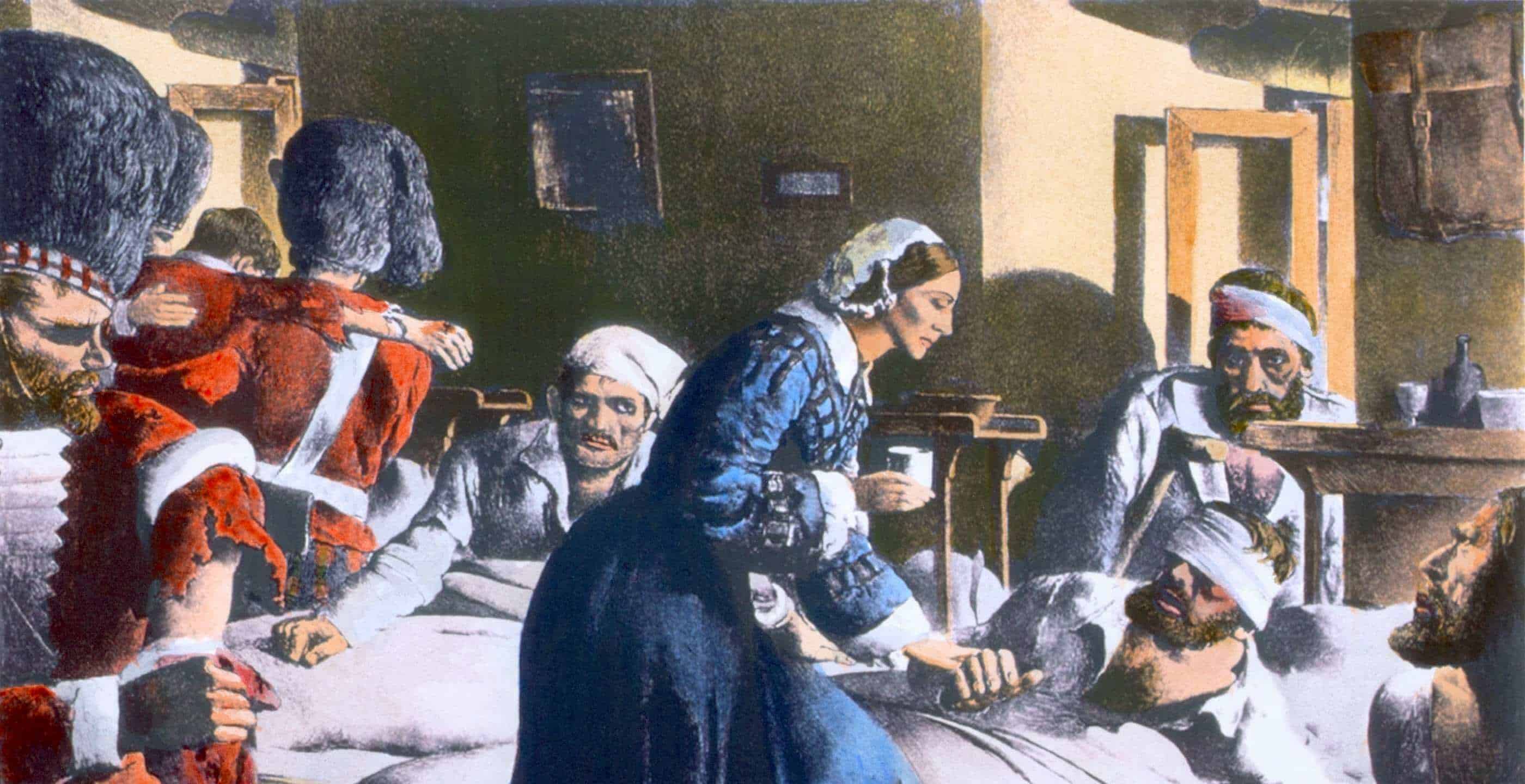

With this in mind, Jenner was determined to find a way to prove this theory. In 1796, he did just that when he conducted an experiment with Sarah Nelmes, a local milkmaid infected with cowpox, extracting pus from her hand and then inserting it into an incision made into the arm of a young, eight year old local boy called James Phipps. The unethical approach was risky but after several days, Jenner exposed the boy to smallpox, finding the boy to be subsequently immune.

Delighted by his discovery, Jenner immediately contacted various people in medical circles who found his approach and ideas unacceptable. The unorthodox and frankly unethical approach he took received an unwelcome response from the Royal Society.

By 1797 he had travelled to London in order to publish his findings, only to discover a hostile reception which forced him to return to Gloucestershire, choosing as he did, to leave some of the lymph taken from the infected milkmaid with a fellow surgeon, Mr Cline, at St Thomas’s Hospital.

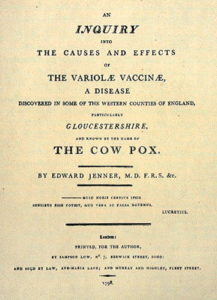

Jenner however had not given up. Realising that to prove such a radical discovery he would need more proof, he began to conduct the experiment on other children, including his own son who was only eleven months old at the time. With a vast amount of data and further examples of successful vaccination he published his findings, coining the word vaccine, taken from the Latin for cow.

Back in London, Cline, the doctor who had been left with the lymph from the milkmaid, would go on to use the sample in order to inoculate a child, which again proved to immunise the patient against subsequent smallpox exposure. It was only after this that acceptance of this discovery grew and the use of it spread.

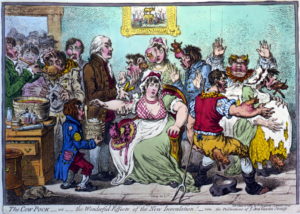

Jenner meanwhile, had to suffer ridicule at the expense of such an unorthodox discovery. In 1802 a cartoon depicted people being given vaccines and sprouting cow heads, making a mockery of his ideas. Nevertheless, with the increasing amount of successful patients being inoculated via this method, the popularity of the vaccine became widespread.

As a result of Jenner’s miraculous medical discovery, he now won much attention in medical circles and amongst the wider general public. As a result he was offered many other opportunities to enhance his career but instead he chose to remain in Berkeley, the place where he felt most comfortable and continued to work on his research in his own time.

Edward Jenner would spend the rest of his days doing what he loved, a fitting tribute to an astounding career which changed the lives of a generation and led to subsequent discoveries revolutionising the field of immunology.

On 26th January 1823, Jenner passed away. He was buried in Berkeley and later commemorated in the form of statues found at Gloucester Cathedral and Kensington Gardens.

For his pioneering work on the smallpox vaccine – the world’s first vaccine – Edward Jenner became known as the ‘father of immunology’. However smallpox vaccination was only made compulsory in 1853, 30 years after Jenner died.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.