It’s a cliché that it takes a lot to rouse the reserved, polite British to action, but during the long hot summer of 1858 it was clear that the time for talking was over. The Mother of Parliaments was deeply offended by the poor personal hygiene of her neighbour, Old Father Thames. The stink from his polluted waters had reached the noses of the politicians in their newly completed Houses of Parliament at Westminster.

As The Times reported it, “The intense heat had driven our legislators from those portions of their buildings which overlook the river. A few members, indeed, bent upon investigating the matter to its very depth, ventured into the library, but they were instantaneously driven to retreat, each man with a handkerchief to his nose.”

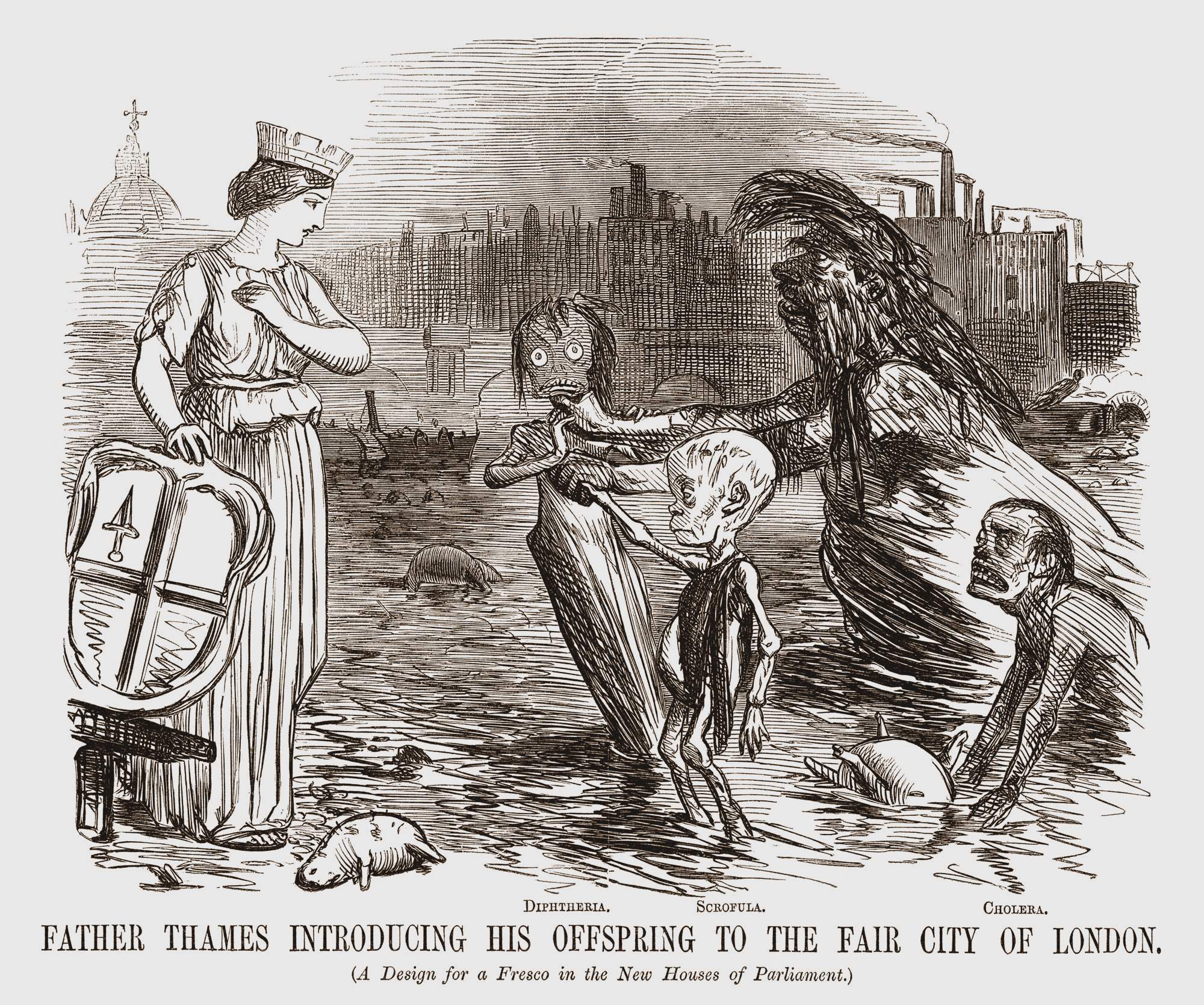

The Thames, used for centuries as a convenient dumping ground for sewage as well as household and industrial waste (not to mention the bodies of the occasional murder victim and executed pirate), was reducing in the summer heat to a bubbling vat of stinking filth. The smell was just the most obvious of the problems. Of greater concern was the threat to health.

The city authorities had always had excrement to deal with but in 1858 it was the sheer scale of the problem. In medieval, Tudor and Stuart times the “night soil” collectors went round the city cleaning out people’s privies. They were known as gold finders, since there was sometimes gold in them thar privies, whether dropped by accident or put there on purpose. It was considered a safe enough place into which none but the most dedicated or desperate thieves would delve. The night soil collectors took their loads away from the city to fertilise farmland, a system that was still in use in rural areas and north east mining villages until well into the 20th century.

During the 17th century, London’s waste had been dealt with by an out of sight, out of mind policy. Cover over the Fleet and Walbrook rivers and use them as sewers – job done. The following century, the 18th, is significant for many reasons, including enlightenment philosophy, the establishment of British imperial policies, and delightful tricorne hats as worn as in Poldark. It was also a great time for the construction of metropolitan sewers, many of which led to cesspits and cesspools which were prone to explosions from the build-up of methane gas.

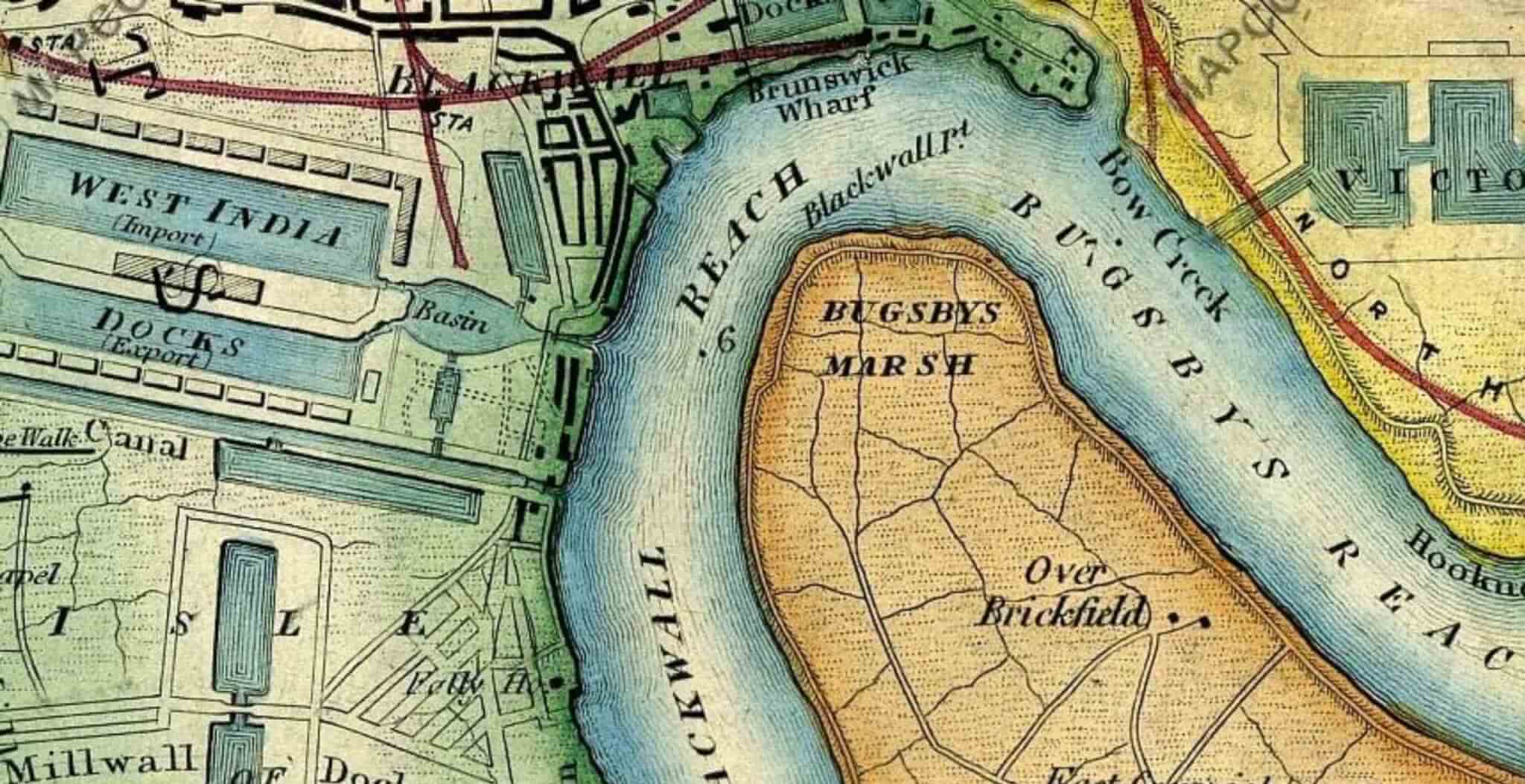

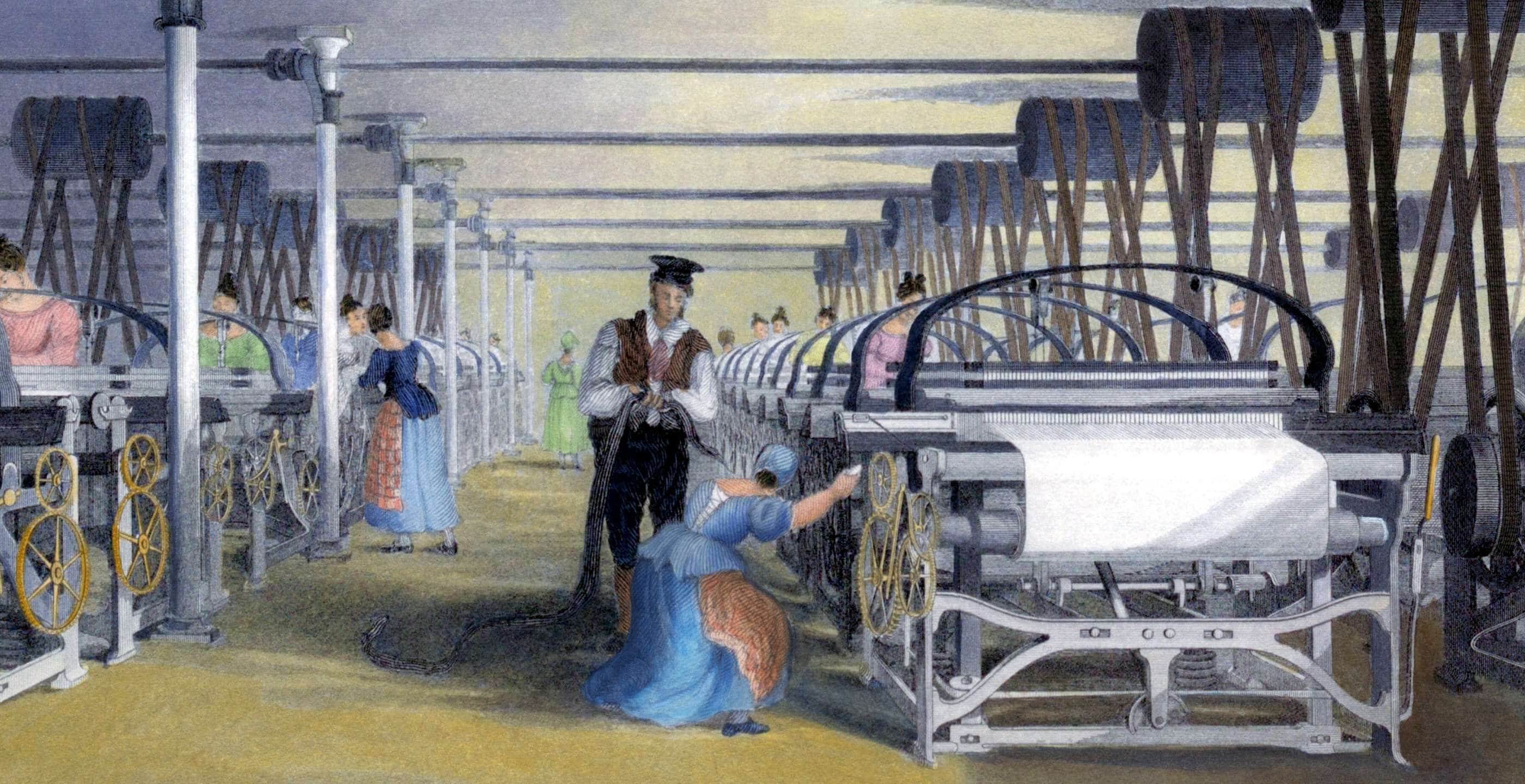

At the start of the 19th century, London was superficially a bustling commercial city undergoing phenomenal population growth. However, beneath the streets lay an infrastructure for supplying water that was still largely medieval, using water pipes made from wood. By the middle of the 19th century the water supply had improved, which meant that Londoners could not only access clean drinking water, but also enthusiastically take up the flushing habit as new-fangled lavatories began to become standard in housing. All the waste ended up in the Thames. The situation was approaching crisis point and the authorities couldn’t claim they hadn’t been warned.

Dramatic landscape artist John Martin had already drawn up detailed plans in the 1820s to resolve the problem of London’s polluted Thames. A friend of the scientist Michael Faraday, Martin was a highly successful landscapist who was as interested in the growing fields of science and technology as he was in art. His paintings were on a massive scale, as was his “grand plan” of 1828, which reveals the depth of his understanding of engineering principles.

The plan would have created an imposing Thames embankment on three levels, extending for four miles on the left bank and somewhat less on the right bank. Plain Doric columns supported each of the levels. The design was created with the traffic of the river in mind, as boats could moor alongside the embankment, where hoists and cranes would be waiting to load and unload cargoes. Within the colonnades would be public walkways running parallel to the river, warehouses and storage areas. (Eventually, no doubt, there would have been a “John Martin Riverside Shopping Mall”.) Enclosed and invisible beneath the colonnaded walk was a large (6m) wide sewer to carry away the waste that would otherwise have polluted the river. The sewage would be filtered and cleaned with technology devised by Martin, so that only clean water went back to the Thames.

It was a design that both impressed the eye and dealt effectively with the problem of London’s sewage. Had it been implemented, it would have created a very different-looking Thames embankment to the one we know today. It would also have provided a very realistic solution to the perennial problem of many an outdoor riverside stroll being ruined by Britain’s unpredictable weather. It formed only part of Martin’s greater scheme for the beautification of London which he had published as “A Plan for Supplying Pure Water to the Cities of London and Westminster, and of Materially Improving and Beautifying the Western Parts of the Metropolis” in 1828. It was probably too far ahead of its time. It wasn’t implemented.

It must have been difficult for Martin to restrain from saying “I told you so” when cholera arrived in London for the first time in 1832, having started in Sunderland the previous year despite quarantine restrictions. 6,536 people died in London, and an estimated 20,000 nationally, as a result of this outbreak. During the second major epidemic in 1848 the death toll in London more than doubled. The third outbreak in 1853–54 claimed 10,738 lives in the capital. Thereafter, the increasingly crowded conditions, poor water supply and failure to deal with sewage and effluent meant that no British city was immune from the risk of cholera.

During the 1848 outbreak, the Times received a letter directly from the people of the capital’s slums: “We live in muck and filth. We aint got no privez, no dust bins, no water splies and no drain or suer in the whole place. If the Colera comes, Lord help us.” It was a nationwide issue; in 1842 Edwin Chadwick had noted in his “Reports on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population” that Glasgow, where 50 per cent of children would never reach their fifth birthday, was “possibly the filthiest and unhealthiest of all British towns”. Chadwick suggested improvements to both water supplies and sewage disposal to reduce disease and mortality rates.

The spectre of cholera looming over London did have positive effects though. Until the middle of the 19th century, medicine, like London’s medieval water supply, reflected the beliefs and technologies of an earlier age. The miasma theory of disease was still the prevalent one. This concept, with its roots in medieval and even earlier times, was based on the idea that disease was borne on the air by mysterious miasma, connected in some vague way with filthy conditions and rotting corpses.

The shrewd and observant physician John Snow was about to challenge that. During the cholera outbreak of 1848 – 49 he noticed that death rates were higher in the areas where water was provided by two companies: the Lambeth, and the Southwark and Vauxhall Water Company. Was the water supply the problem? He published a paper in 1849 entitled “On the Mode of Communication of Cholera”, putting forward his theory. It had little effect.

When cholera broke out again in 1854, Snow observed a high number of deaths in Broad Street, Soho, where people used a communal water pump. He removed the handle so the pump couldn’t be used and there were no further deaths on that street. The water had been contaminated by a nearby cesspool through a crack in its bricks. He published his results. The authorities carried on muttering “Nonsense, it’s miasma, everyone knows that!” and ignored it.

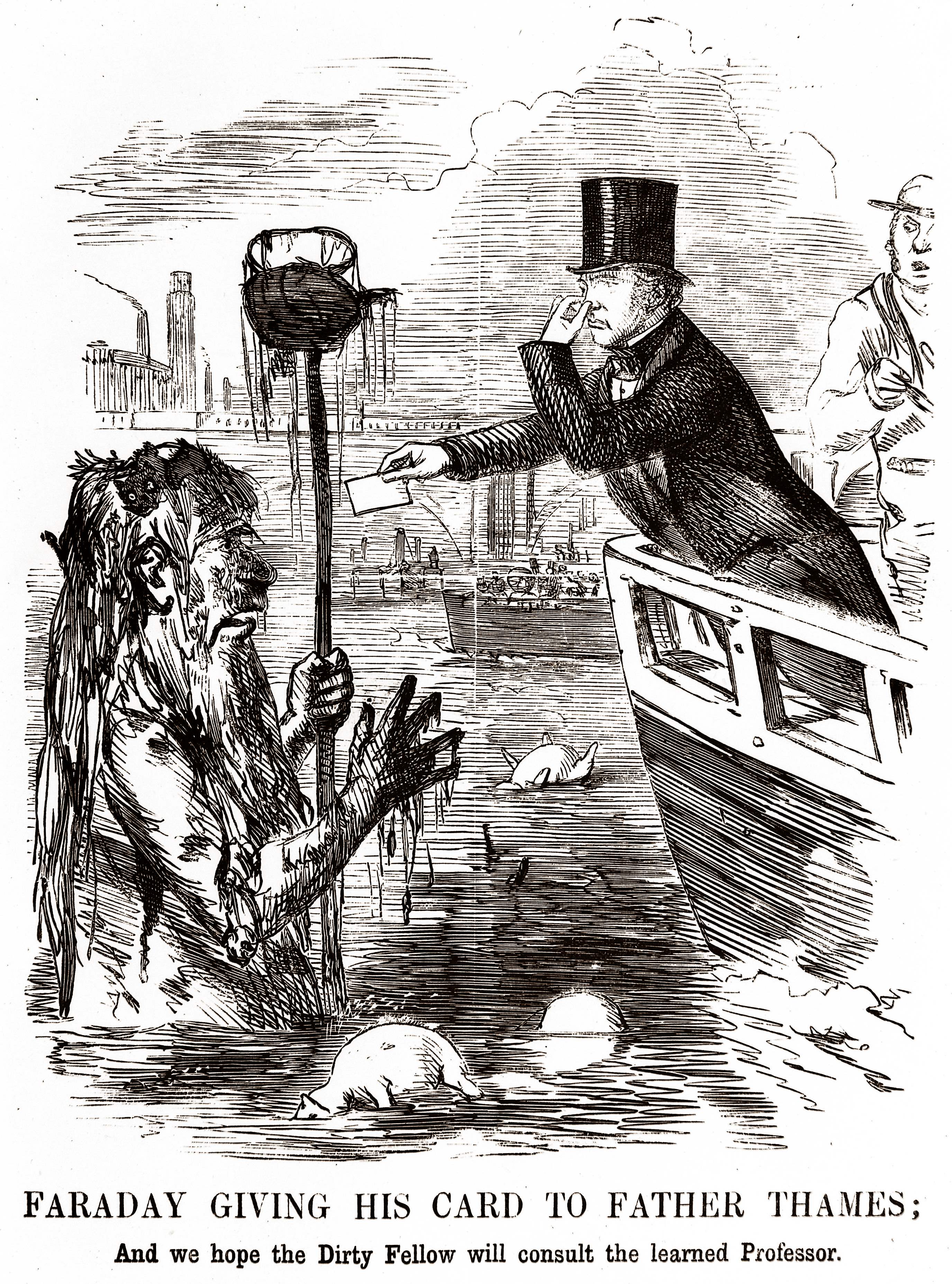

A sea change in medicine was due, and in time it happened, with the work of pioneers such as Louis Pasteur, Joseph Lister, Ignaz Semmelweiss and Robert Koch eventually receiving recognition. It was the Great Stink of 1858 bowling over the politicians that finally got some results, though. Even the investigations of eminent scientist Michael Faraday a few years prior to the stink hadn’t been enough to kick the government into action. He took a trip along the Thames to see its condition for himself, describing in a letter to the Times how he dropped bits of paper into the river as he went along in order to test its visibility. He told the press how “Near the bridges the feculence rolled up in clouds so dense that they were visible at the surface… the whole river was for the time a real sewer”.

The government’s response during the early days of the stink was to douse the curtains of the Houses of Parliament in chloride of lime, before embarking on a final desperate measure to cure lousy old Father Thames by pouring chalk lime, chloride of lime and carbolic acid directly into the water. No doubt muttering “It’s the miasma, you know!” while it was being poured.

This time it wouldn’t wash. Just to prove that legislators can act with speed when spurred on by nausea, the politicians rushed through a bill to remedy the problem and signed it into law in eighteen days, a record time. The Times was to hand with its usual sardonic commentary, noting that they ignored Faraday and only sprang into action when their “proximity to the source of the stench concentrated their attention on its causes in a way that many years of argument and campaigning had failed to do…”

Cometh the hour, cometh the man. Consultant engineer Joseph Bazalgette, who was already working as a surveyor for the Metropolitan Commission of Sewers, was employed to mastermind a plan for sewers, pumping stations and the redevelopment of the embankments of London. The results of his remarkable efforts are still maintaining London’s health today. The Great Stink may not have the historic cachet of the Great Fire or the Plague of London, but its influence was ultimately to the good of the city.