The term ‘hangover’ is universally understood to mean the disproportionate suffering that comes after a night of over-indulgence. But where does the term actually come from? One possible explanation is, somewhat strangely, Victorian England.

During the Victorian era the practice of paying for a ‘two-penny hangover’ was incredibly popular among the country’s homeless population and the term ‘two penny hangover’ was so commonly used that it made its way into contemporary literature. A two-penny hangover is not the description of a very cheap night out, nor is it the amount it would cost you to get drunk in Victorian England. It is actually somewhere you could go to sleep if you were one of the thousands of homeless and destitute living in the country’s main cities at the time. If you lived on the streets and had managed to make some money during the day, depending on how much you had, you could spend the night in one of three ways; paying a penny to sit-up, two pence to ‘hang-over’, or 4 or five pennies to lie down.

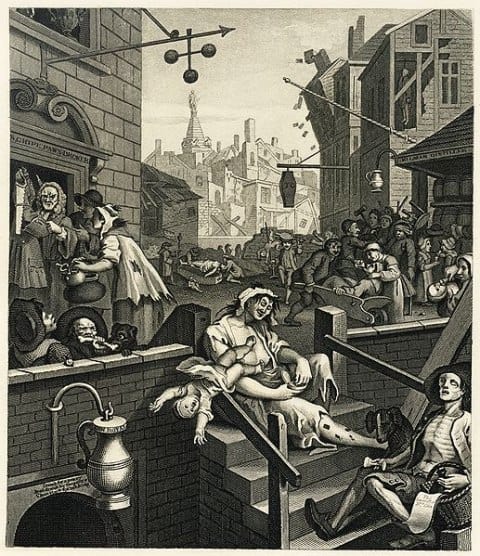

Victorian society was struggling to pull itself out of centuries of poverty, degradation and ‘Mother’s Ruin’. It could be argued that society was suffering from a collective hangover from the country’s previous struggles through the industrial revolution, disease outbreaks and poor laws of the 18th century. In contrast, for some people at least, Victorian England was also a period and place of prosperity and innovation.

Hogarth‘s ‘Gin Lane’

Hogarth‘s ‘Gin Lane’

The population of Britain at the time lived in both amazing luxury and devastating poverty. The first time the term ‘Victorian’ was used was in 1851. Queen Victoria had been ruling since 1837, and would in fact go on to rule until 1901. 1851 was also the year of The Great Exhibition, this showed off the very best of industrialisation and innovation from Britain and around the world. This exposition, based in London, was visited by over 6 million people, rich and poor alike.

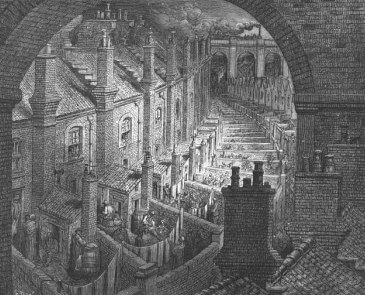

Victorian England exemplified a capitalist entrepreneurial work ethic, a sense of individualism and hard work. It is no coincidence that Darwin’s ‘Origin of the Species’ was also published at this time. The popularity of his work further cemented the idea of ‘survival of the fittest’ into the public consciousness. Unfortunately what brought prosperity to some brought degradation to others. This was coupled with a ‘laissez faire’ economic approach from the government which saw a surge in poverty in England’s cities. Although the Empire was flourishing, unfortunately so were the cities’ slums, especially London’s.

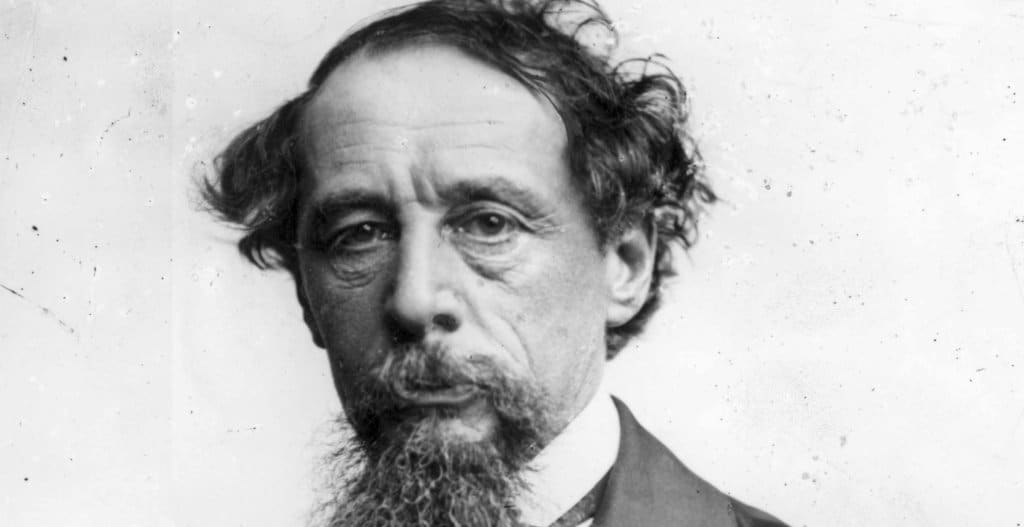

The population had tripled in the 19th century and there were simply not enough resources to go around. People migrated from the countryside into cities causing overcrowding and lack of work for many. Starvation and degradation were, unfortunately, commonplace. There is a reason that Victorian England is often portrayed in contemporary literature as a dark and depressing palace for its poorest inhabitants. There were 30,000 homeless children in London alone during this time. It is therefore unsurprising that there was so much reference to poverty in contemporary literature. From the street urchins in Dickens’ ‘Oliver Twist’ to the child chimney sweeps in Charles Kingsley’s ‘The Water Babies’. In fact Dickens actually used one of London’s most notorious and overcrowded slums, or ‘rookeries’ as they were called, ‘Saffron Hill’, as Fagin’s lair for the vagrant children he trained as ruthless pickpockets. For the poorest members of Victorian society life was incredibly hard, especially if you were homeless. It was even harder at night, where as well as contending with exposure and hunger, there were also the added dangers associated with the fall of darkness. If you were homeless you had very limited options. However, if you managed to scrounge up a penny you could at least get out of the rain at a ‘penny sit-up’.

Penny sit-ups

These are exactly as you would imagine them to be. For a penny a homeless person could pay to ‘sit up’ on a bench all night in a hall. Oftentimes this was the only option for people to get off the streets, particularly desirable in England’s wet and freezing winters. Sometimes the rooms would be heated but sometimes they wouldn’t, and the homeless person could also be provided with food but that wasn’t always guaranteed either. The only downside to these arrangements was that they weren’t actually supposed to sleep in these ‘sit-ups’. Some places even went as far as to employ monitors to ensure that no one fell asleep, as the right to sleep was not included in the penny price. It would seem that the majority of the homeless who used these sit-ups were men, but women and children were also documented as having frequented them. Although safer than the streets, most were still associated with being places of squalor, poverty and discomfort.

Two-penny hangovers

For an extra penny you could pay to sleep literally hanging over a rope. This was possibly marginally more comfortable, as if you fell asleep the rope would prevent you from slipping onto the floor or head-butting the bench in front of you. It still wouldn’t have been an overly relaxing experience though. People were crammed in as tightly as possible, and to make sure you got your money’s worth but no more, the rope would be unceremoniously cut the next morning at 5 or 6am. This was done for the dual purpose of freeing up the space, but it also served as a reminder to those lowest in society of just where their place was. Once the rope was cut, the homeless would be kicked out onto the streets once more. Even with the protection that these places offered, they were also not necessarily heated and it was not unheard of for there to be one or two people who could not be woken the next morning, having frozen to death during the night.

The term hangover is unlikely to have come specifically from this practice, it more likely refers to the lasting after effects of alcohol felt the next day. However the two-penny hangovers remained a grim reality of Victorian England regardless of the tenuous link to the etymology of alcohol. Particularly as ‘two-penny hangovers’ have also been mentioned in Paris, and the French for ‘hangover’ is ‘gueule de bois’ which is literally ‘mouth of wood” so nothing to do with ‘hanging over’ at all. But a fairly accurate description of how your mouth feels after a night drinking gin!

Salvation Army Coffins

Perhaps the creepiest of these peculiar Victorian sleeping arrangements, for those too poor to have a fixed place to sleep, were the four or five penny coffins. Thankfully they weren’t actually coffins. Instead they were small wooden boxes that bore a striking and unpleasant resemblance to coffins. They would be laid out in rows on the floor, and because the idea was to accommodate as many homeless people as possible, the dimensions of the ‘coffins’ were small and not very comfortable. People would also be given an oilcloth or leather blanket to cover themselves with. Often the price would include a cup of tea or coffee and a piece of bread as well. Inevitably people that used them would wake up cramped and sore the next day, although considering they were sleeping in coffins it was likely considered a bonus that they woke up at all!

However, these makeshift beds were still very much appreciated, as compared to the two previous options, at least in the ‘coffins’ you could lie down horizontally and sleep properly. These coffins were one of England’s first attempts at homeless shelters, and they were started by The Salvation Army, which was itself founded in 1865. The sheer levels of homeless and destitute had been noticed by the recently formed Christian charitable organisation, and this was one of the earliest solutions. In fact, in one contemporary newspaper the number of people using such a shelter nightly in Sheffield was estimated at between 200-300 people a night. The need was clearly very great. Time progressed though and in the latter half of the century homeless shelters began to operate free of charge, doing away with these early unusual solutions.

These peculiar sleeping arrangements have been commented upon by both Charles Dickens in his ‘Pickwick Papers’, which were published in 1836, and George Orwell’s work ‘Down and Out in London and Paris’ published in 1933, which he wrote whilst living as a vagrant for research. It is unsurprising that these scenarios are used in fiction as they do sound fanciful but as is often the case, the truth is stranger than the fiction.

Two-Penny Hangovers in literature:

“The Twopenny Hangover. This comes a little higher than the Embankment. At the Twopenny Hangover, the lodgers sit in a row on a bench; there is a rope in front of them, and they lean on this as though leaning over a fence. A man, humorously called the valet, cuts the rope at five in the morning.”

– ‘Down and Out in London and Paris’ George Orwell.’

“The Coffin, at fourpence a night. At the Coffin you sleep in a wooden box, with a tarpaulin for covering. It is cold, and the worst thing about it are the bugs, which, being enclosed in a box, you cannot escape.”

– ‘Down and Out in London and Paris, George Orwell.’

“And pray, Sam, what is the twopenny rope?’ inquired Mr. Pickwick.

‘The twopenny rope, sir,’ replied Mr. Weller, ‘is just a cheap

lodgin’ house, where the beds is twopence a night.’

‘What do they call a bed a rope for?’ said Mr. Pickwick…They has two

ropes, ’bout six foot apart, and three from the floor, which goes

right down the room; and the beds are made of slips of coarse

sacking, stretched across ’em.’

‘Well,’ said Mr. Pickwick.

‘Well,’ said Mr. Weller, ‘the adwantage o’ the plan’s hobvious.

At six o’clock every mornin’ they let’s go the ropes at one end,

and down falls the lodgers.”

– ‘The Pickwick Papers’, Charles Dickens.’

By Terry MacEwen, Freelance Writer

Published: September 8, 2020.