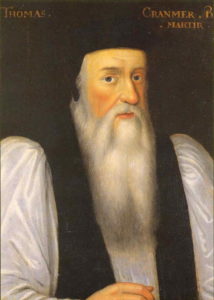

A Protestant martyr in the reign of Bloody Mary, Thomas Cranmer was a significant figure, serving as the first Protestant Archbishop of Canterbury.

On 21st March 1556, Thomas Cranmer was burnt at the stake for heresy. Identified as one of the most influential religious characters of his time in England, a leader of the Reformation and pioneering ecclesiastical figure, his fate had been sealed.

Born in 1489 in Nottinghamshire to a family with important connections as local gentry, his brother John was destined to inherit the family estate, whilst Thomas and his other brother Edmund pursued different paths.

By the age of fourteen, young Thomas was attending Jesus College, Cambridge and received a typical classical education consisting of philosophy and literature. At this time, Thomas embraced the teachings of humanist scholars such as Erasmus and completed a Master’s degree followed by an elected Fellowship at the college.

However, this was short-lived, as not long after completing his education, Cranmer married a woman called Joan. With a wife in tow, he was subsequently forced to relinquish his fellowship, even though he was not a yet a priest and instead he took up a new position.

When his wife later died in childbirth, Jesus College saw fit to reinstate Cranmer and in 1520 he became ordained and six years later received his Doctor of Divinity degree.

Now a fully-fledged member of the clergy, Cranmer spent many decades based at Cambridge University where his academic background in philosophy held him in good stead for a lifetime of biblical scholarship.

In the meantime, like many of his Cambridge colleagues he was selected for a role in the diplomatic service, serving at the English embassy in Spain. Whilst his role was minor, by 1527 Cranmer had encountered King Henry VIII of England and spoken with him one-on-one, leaving with an extremely favourable opinion of the king.

This early encounter with the monarch would lead to further contact, especially when Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon was splintering. With the king keen to find support for his annulment, Cranmer stood up and accepted the task.

The king had for some time been disgruntled at not having produced a son and heir to his throne. He subsequently gave the highly influential religious figure of Cardinal Wolsey the task of seeking an annulment. In order to do so, Wolsey engaged with various other ecclesiastical scholars and found Cranmer willing and able to provide assistance.

In order to complete this process, Cranmer investigated the necessary channels in order to find a path to annulment. Firstly, engaging with fellow Cambridge scholars, Stephen Gardiner and Edward Foxe, the idea of finding support from fellow theologians on the continent was broached as the legal framework for a case with Rome was a more difficult hurdle to navigate.

By casting a wider pool, Cranmer and his compatriots executed their plan with the approval of Thomas More who allowed Cranmer to go on a research trip to canvass opinions from the universities. Meanwhile Foxe and Gardiner worked on implementing a rigorous theological argument in order to sway opinion in favour of the belief that the king had ultimate supreme jurisdiction.

On Cranmer’s continental mission he encountered Swiss reformers such as Zwingli who had been instrumental in executing the reformation in his home country. Meanwhile, the humanist Simon Grynaeus had warmed to Cranmer and subsequently contacted Martin Bucer, an influential Lutheran based at Strasbourg.

Cranmer’s public profile was growing and by 1532 he had been appointed at the court of Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor as the resident ambassador. A pre-requisite of such a role was to accompany the emperor on his travels through his European realm, thus visiting important theological hubs of activity such as Nuremberg where reformers had instigated a wave of reform.

This was Cranmer’s first-hand exposure to the ideals of the Reformation. With increasing contact with some of the many reformers and followers, little by little the ideas extolled by Martin Luther began to resonate with Cranmer. Moreover, this was reflected in his private life when he married Margarete, the niece of a good friend of his called Andreas Osiander who also happened to be an instrumental figure in the reforms executed in the now Lutheran city of Nuremberg.

In the meantime, his theological progress rather disappointingly was not matched by his attempt at garnering support for the annulment from Charles V, Catherine of Aragon’s nephew. Nevertheless, this did not appear to have an adverse effect on his career as he was subsequently appointed Archbishop of Canterbury following the death of the current archbishop William Warham.

This role was secured largely due to the influence of Anne Boleyn’s family, who had a vested interest in seeing the annulment secured. Cranmer himself was however, rather taken aback by the proposal after only serving in a more minor capacity in the Church. He returned to England and on 30th March 1533 was consecrated as Archbishop.

With his newly acquired role bringing him prestige and status, Cranmer remained undeterred in his pursuit of annulment proceedings which became even more important after Anne Boleyn’s revelation of pregnancy.

In January 1533, King Henry VIII of England married his lover Anne Boleyn in secret, with Cranmer being left out of the loop for a full fourteen days, despite his obvious involvement.

With much urgency, the king and Cranmer looked into the legal parameters for ending the royal’s marriage and on 23rd May 1533, Cranmer announced that King Henry VIII’s marriage with Catherine of Aragon was against the law of God.

With such an announcement by Cranmer, Henry and Anne’s union was now confirmed and he was bequeathed the honour of presenting Anne with her sceptre and rod.

Whilst Henry could not have been happier with this outcome, back in Rome, Pope Clement VII was incandescent with rage and had Henry excommunicated. With the English monarch defiant and steadfast in their decision, in September the same year, Anne gave birth to a baby girl called Elizabeth. Cranmer himself performed the baptism ceremony and served as godparent to the future queen.

Now in a position of power as Archbishop, Cranmer would lay the foundations of the Church of England.

Cranmer’s input in securing the annulment was to have enormous ramifications on the future theological culture and society of a nation. Instilling the conditions for England’s separation from the Papal Authority, he, alongside figures such as Thomas Cromwell made the argument for Royal Supremacy, with King Henry VIII considered leader of the church.

This was a time of great change in religious, social and cultural terms and with Cranmer fast becoming one of the influential figureheads at this time. Whilst serving as archbishop he created the conditions for a new Church of England and established a doctrinal structure for this new Protestant church.

Cranmer was not without opposition and thus any significant changes to the Church remained highly contested by the religious conservatives who fought this tide of ecclesiastical change.

That being said, Cranmer was able to publish the first official vernacular service, the Exhortation and Litany in 1544. Whilst in the nucleus of the English Reformation, Cranmer constructed a litany which reduced the veneration of saints to appeal to the new Protestant ideals. He, with Cromwell, endorsed the translation of the Bible into English. Old traditions were being replaced, transformed and reformed.

Cranmer’s position of authority continued when Henry VIII’s son Edward VI succeeded the throne and Cranmer continued with his plans for reformation. In this time he produced the Book of Common Prayer which amounted to a liturgy for the English Church in 1549.

A further revised addition was published under Cranmer’s editorial scrutiny in 1552. However his influence and the publication of the book itself very quickly came under threat when Edward VI sadly passed away only a few months later. In his place, his sister, Mary I, a devout Roman Catholic restored her faith in the country and thus banished the likes of Cranmer and his Book of Prayer to the shadows.

By this time, Cranmer was a significant and well-known figurehead of the English Reformation and as such, became a prime target of the new Catholic queen.

In the autumn, Queen Mary ordered his arrest, placing him on trial on the charges of treason and heresy. Desperate to survive his impending fate, Cranmer renounced his ideals and recanted but to no avail. Imprisoned for two years, Mary had no intentions of saving this Protestant figurehead: his destiny was his execution.

On 21st March 1556, the day of his execution, Cranmer boldly withdrew his recantation. Proud of his beliefs, he embraced his fate, burning at the stake, dying a heretic to the Roman Catholics and a martyr for the Protestants.

“I see the heavens open, and Jesus standing at the right hand of God”.

His last words, from a man who changed the course of history in England forever.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 12th June 2022