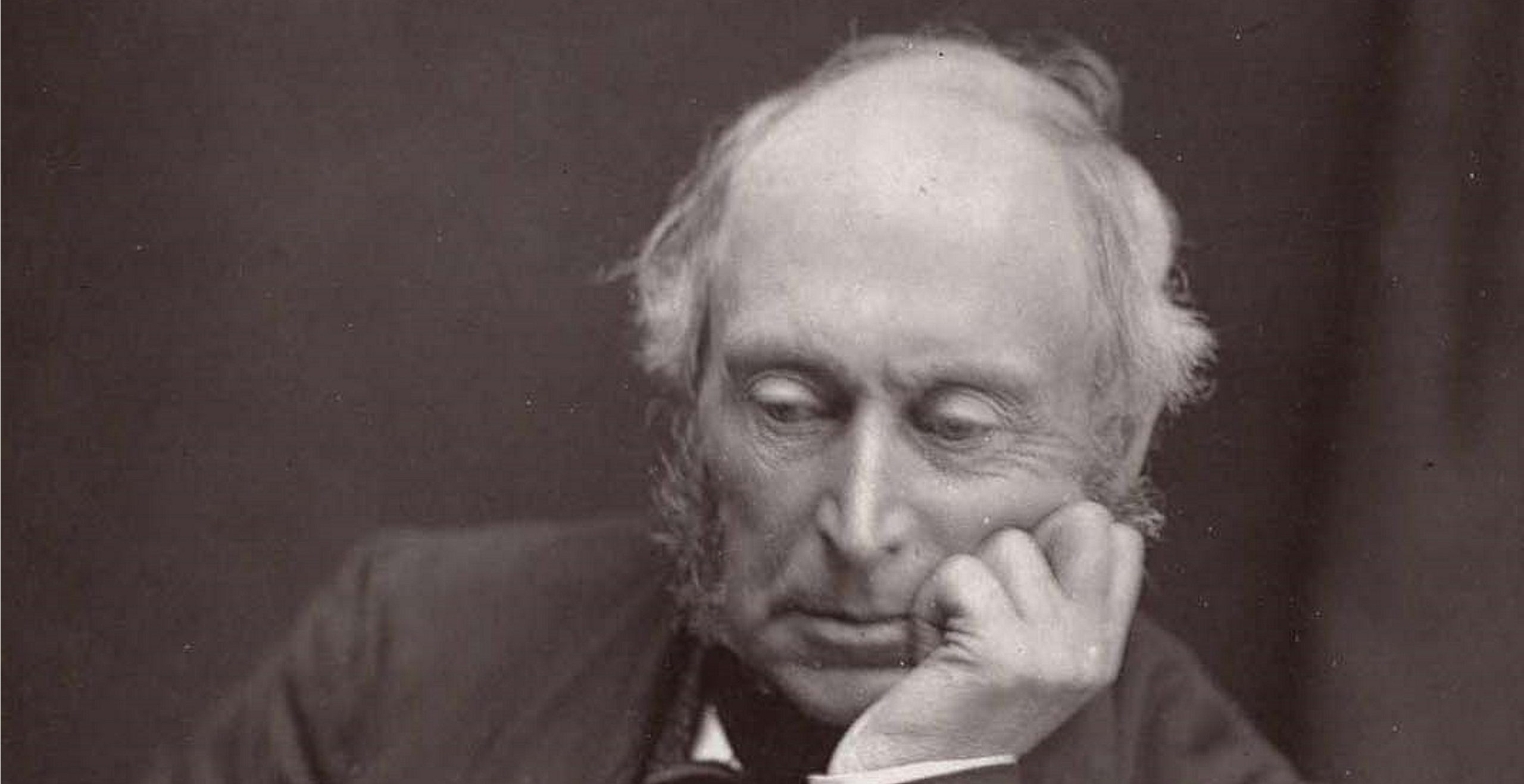

An inventor, industrialist and philanthropist. These are just some of the roles fulfilled by William Armstrong, the 1st Baron Armstrong during his lifetime.

His story began in Newcastle upon Tyne. Born in November 1810, Armstrong was the son of an up-and-coming corn merchant (also called William) who worked along the quayside. In time, his father would manage to scale the upper echelons to become mayor of Newcastle in 1850.

Meanwhile, young William would benefit from a good education, attending the Royal Grammar School and later another grammar school, Bishop Auckland, in County Durham.

From an early age he expressed an interest and aptitude in engineering and was a frequent visitor to the local engineering works belonging to William Ramshaw. It was here that he was introduced to the owner’s daughter, Margaret Ramshaw, who would later become William’s wife.

Despite his obvious talents in the field of engineering, his father had his mind set on a career in law for his son and insisted upon it, leading him to contact a solicitor friend in order to introduce his son to the business.

William would end up honouring his father’s wishes and travelled to London where he would study law for five years before returning to Newcastle and becoming a partner in his father’s friend’s law firm.

By 1835, he had also married his childhood sweetheart Margaret and they had set up a family home in Jesmond Dene on the outskirts of Newcastle. Here they created a beautiful parkland with newly planted trees and an abundance of wildlife to enjoy.

In the coming years, William would remain dedicated to pursuing the career his father had chosen for him. He worked as a lawyer for the next decade of his life, until his early thirties.

In the meantime, his spare moments would be taken up by his engineering interests, constantly pursuing experiments and engaging in research, particularly in the field of hydraulics.

This dedication to his true passion produced an outstanding result two years later when he managed to develop the Armstrong Hydroelectric machine which, despite its name, actually generated static electricity.

His fascination with engineering and his ability to invent machinery eventually led him to abandon his law career and start up his own company dedicated to building hydraulic cranes.

Fortunately for Armstrong, his father’s friend and partner in his law firm, Armorer Donkin, was very supportive of his change in career. So much so, that Donkin even provided funds for Armstrong’s new business.

By 1847, his new firm called W.G. Armstrong and Company bought land in nearby Elswick and set up a factory there which would become the base of a successful business producing hydraulic cranes.

After his initial success in this venture, there was plenty of interest in Armstrong’s new technology and orders for hydraulic cranes increased, with requests coming from as far afield as the Liverpool Docks and the Edinburgh and Northern Railways.

In no time at all, the use of and demand for hydraulic machinery at docks all around the country resulted in the company expansion. By 1863, the business employed nearly 4000 workers, a substantial increase from its modest beginnings with around 300 men.

The company would produce, on average, around 100 cranes a year but such was their success that the factory branched out into bridge building, the first being completed in 1855 in Inverness.

William Armstrong’s business acumen and engineering capabilities allowed him to tackle a multitude of large construction and infrastructure projects in his lifetime. In addition to the hydraulic cranes, he also established the hydraulic accumulator alongside fellow engineer John Fowler. This invention made water towers such as Grimsby Dock Tower obsolete as the new invention proved more effective.

By 1864 recognition for his work was growing, so much so that William Armstrong was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society.

In the meantime, unfolding international conflicts such as the Crimean War had necessitated new inventions, adaptations and quick thinking in order to successfully meet all of the engineering, infrastructure and armament challenges the war presented.

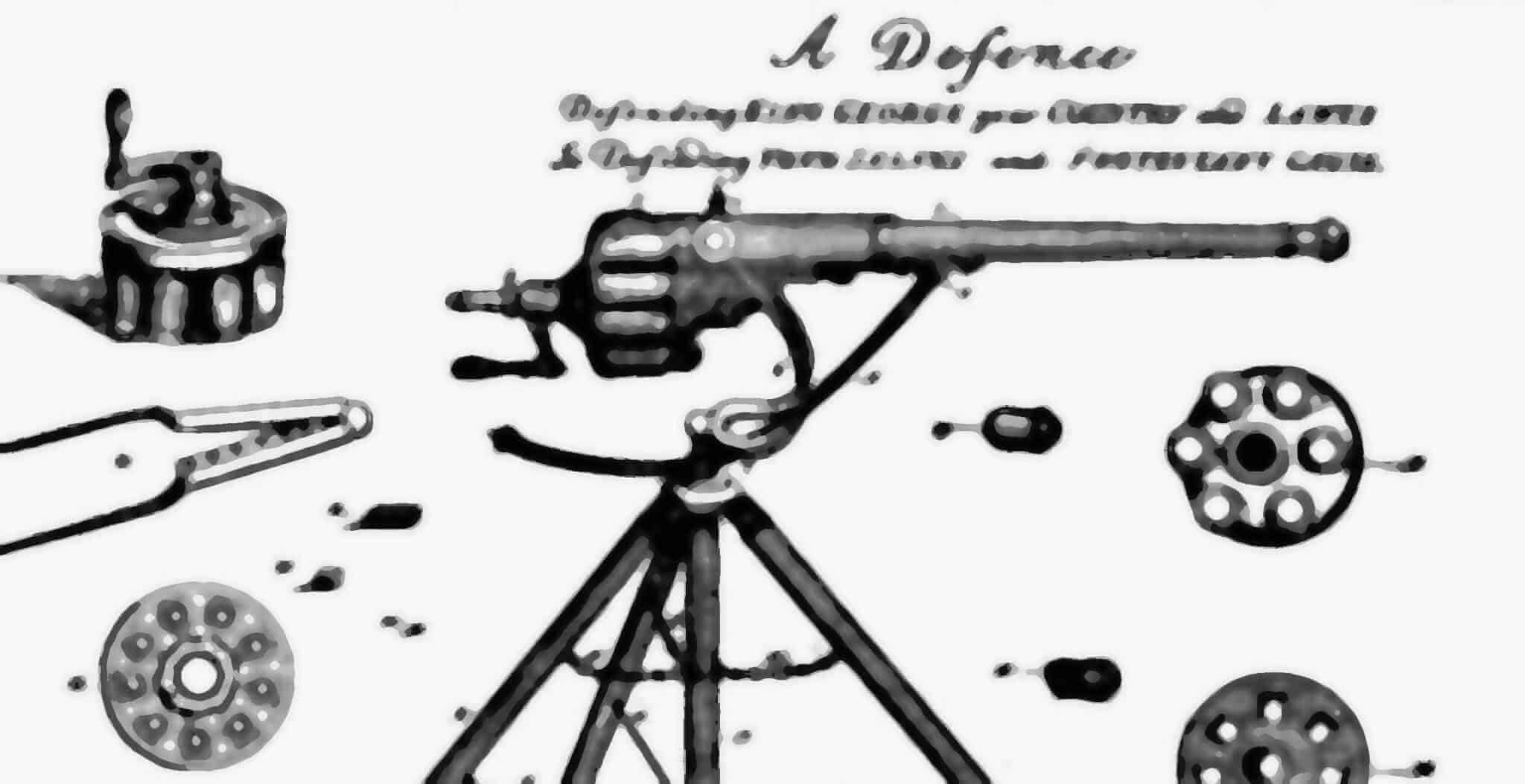

William Armstrong would prove to be very capable in the field of artillery and provided enormous help when he began to design his own gun after reading of the difficulties of heavy field guns within the British Army.

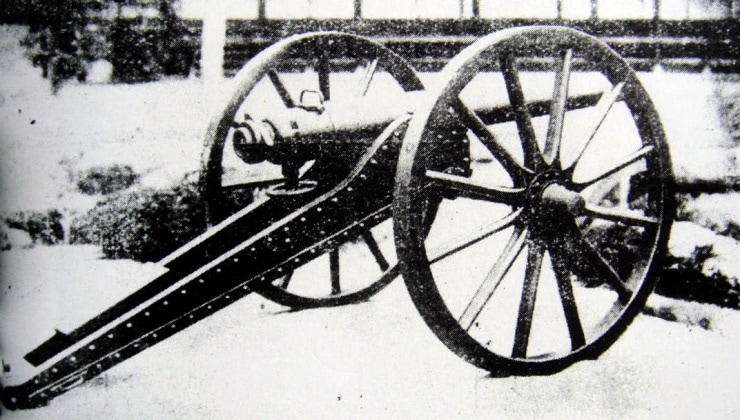

It had been said that it could take up to 150 soldiers three hours to haul two-ton guns into position without the use of a horse. In no time at all, Armstrong had produced a lighter prototype for the government to inspect: a 5 lb breech-loading wrought iron gun with a strong barrel and steel inner lining.

Upon initial examination, the committee showed interest in his design however they required a higher calibre gun and so Armstrong went back to the drawing board and built one of in the same design but this time at a weightier 18 lbs.

The government approved his design and Armstrong handed over the patent for his gun. In response to his significant contribution he was made a Knight Bachelor and had an audience with Queen Victoria.

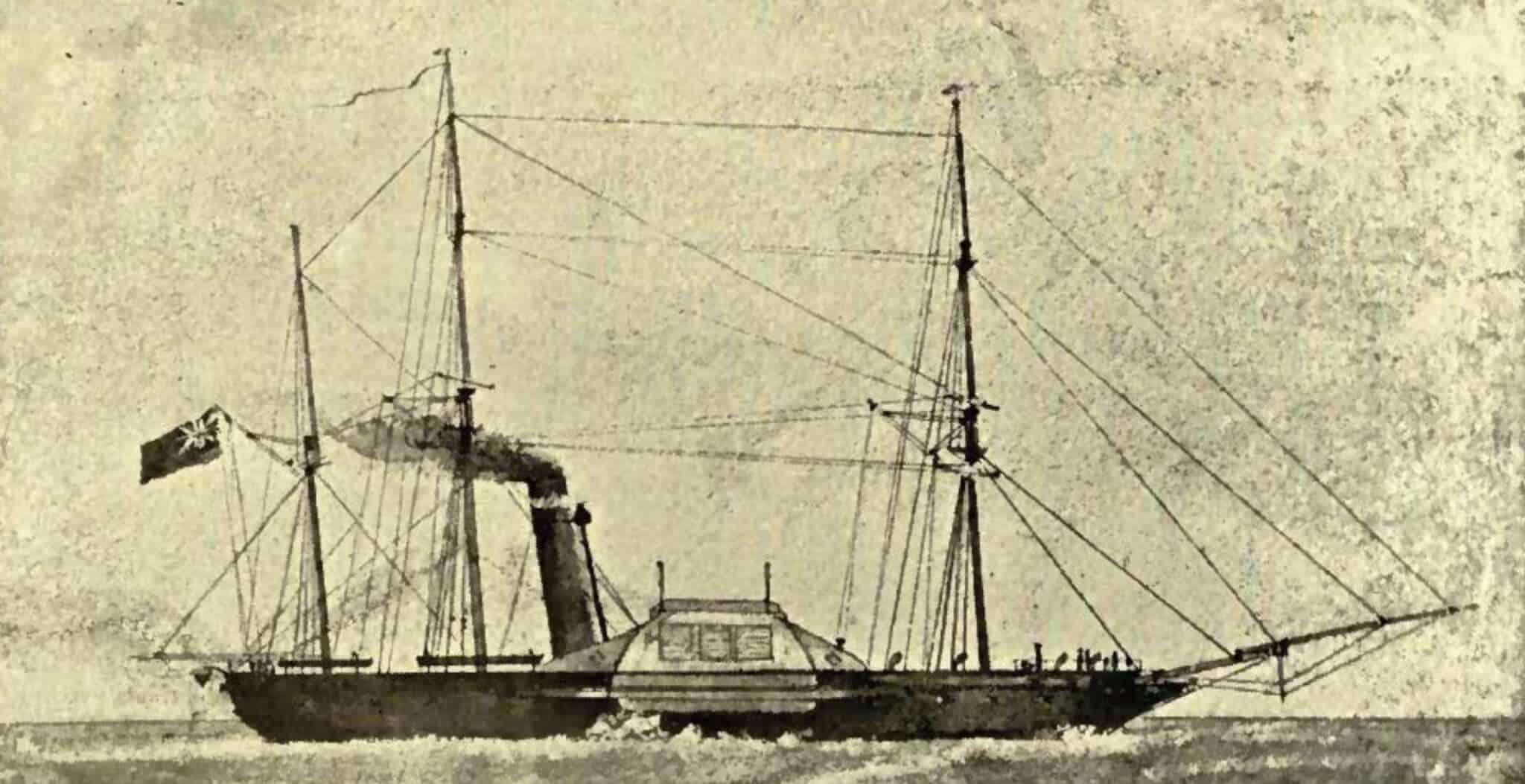

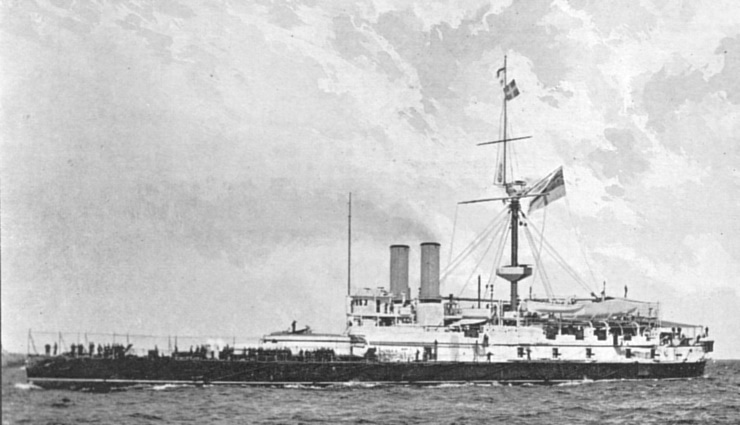

Armstrong’s crucial work in armaments also saw him become an engineer of the War Department and he set up a new company called Elswick Ordnance Company with which he had no financial connections, to manufacture armaments solely for the British government. This included 110 lb guns for the iron battleship Warrior, the first of their kind.

Unfortunately, Armstrong’s success in armament production was met with concerted efforts to discredit him by the competition and changing attitudes to the use of these guns meant that by 1862 the government ceased its orders.

Punch magazine even went as far as to label him Lord Bomb and describe Armstrong as a warmonger for his involvement in the arms trade.

Despite these setbacks, Armstrong continued with his work and in 1864 his two companies were merged into one when he resigned from the War Office, ensuring there was no conflict of interest for his future production of guns and naval artillery.

The war ships Armstrong worked on included torpedo cruisers and the impressive HMS Victoria launched in 1887. At this time the company produced ships for many different nations, with Japan being one of its largest customers.

In order for the business to continue to prosper, Armstrong made sure he employed top-rated engineers of the highest calibre including Andrew Noble and George Wightwick Rendel.

However, the production of warships at Elswick had been restricted by an older, low arched stone bridge over the River Tyne in Newcastle. Armstrong naturally found an engineering solution to this problem by building Newcastle’s Swing Bridge in its place, giving much larger ships access to the River Tyne.

Armstrong spent many years invested in the company, but in time he would take a step back from the day-to-day management and look for a tranquil setting to spend his free time. He would find this location in Rothbury where he built the Cragside estate, an impressive house surrounded by amazing natural beauty. The estate become an extensive personal project which included five artificial lakes and millions of trees on almost 2000 acres of land. His home would also be the first in the world to be lit by hyrdro-electricity which was generated by the lakes on the vast estate.

Cragside would become Armstrong’s main residence as he passed on his home in Jesmond Dene to the city of Newcastle. Meanwhile, the grand estate at Cragside would play host to a number of prominent figures including the Prince and Princess of Wales, the Shah of Persia and a number of prominent leaders from across the Asian continent.

William Armstrong had become extremely successful and Cragside epitomised not only his wealth but his attitude towards new technology and the natural world.

He would during his lifetime use his riches for the greater good such as donating to the establishment of the Newcastle Royal Infirmary.

His philanthropy spread far and wide as he became a benefactor to various organisations, many practical as well as academic since he was passionate about encouraging the next generation.

His involvement in academia was evident when Armstrong College of the University of Durham was named after him and would later transform into the University of Newcastle.

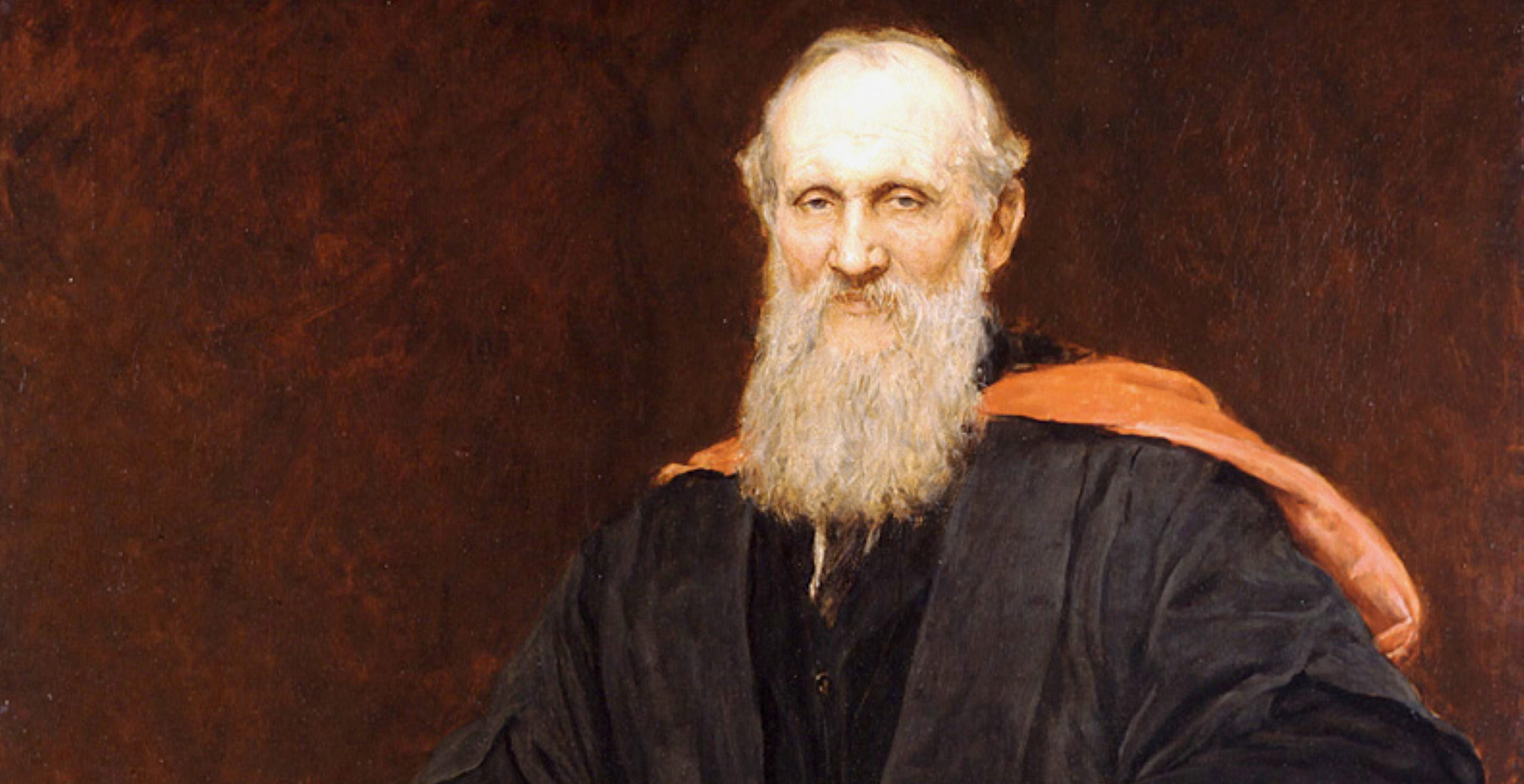

He would also serve in a variety of honorary roles in later life, such as President of the Institution of Civil Engineers, as well as achieving a peerage to become Baron Armstrong.

Sadly, in 1893 his wife Margaret passed away and since William and Margaret had no children of their own, Armstrong’s heir presumptive was his great-nephew William Watson-Armstrong.

Now in old age, one might have expected William to slow down. However, he had one final, grand project up his sleeve. In 1894 he bought Bamburgh Castle on the beautiful Northumberland coastline.

The castle, which was steeped in historical significance, had fallen on hard times during the seventeenth century and required significant restoration. Nevertheless, it was lovingly renovated by Armstrong who ploughed a huge sum of money into its refurbishment.

Today, the castle remains within the Armstrong family and retains its stunning heritage thanks to William.

This was to be his last big project as he passed away at Cragside in 1900 at the age of ninety.

William Armstrong left behind a substantial legacy in a variety of different fields proving himself to be a visionary who helped to propel Victorian Britain to the front and centre in its industrial and scientific expertise.

In many ways, William Armstrong was ahead of his time and keen to embrace new technologies. His work made significant contributions not only to his local area of Northumberland but to the country, and arguably the world, as a whole.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 10th November 2021.