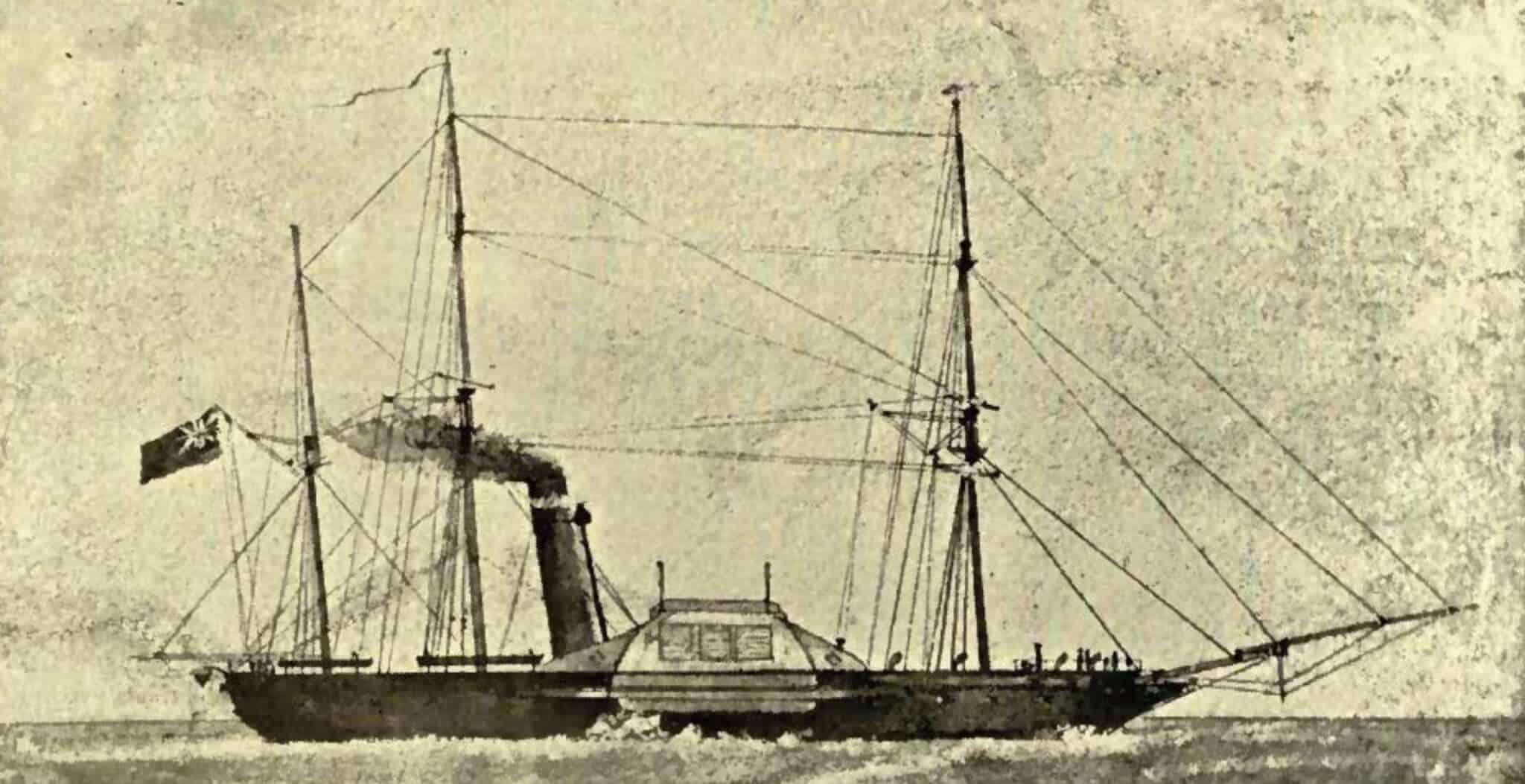

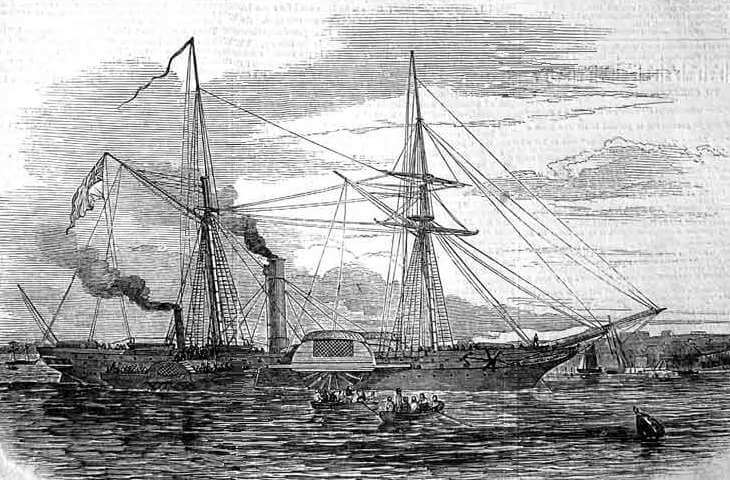

Under the command of Captain Robert Salmond, H.M.S. Birkenhead left Portsmouth in January 1852 taking troops to fight in the Frontier War in South Africa. The Birkenhead, one of the first iron hulled paddle steamers in service travelled to southern Ireland, before heading for the Cape on 17th January.

The troops onboard included fresh drafts of Fusiliers, Highlanders, Lancers, Foresters, Rifles, Green Jackets and assorted other regiments of the British Army.

After taking on fresh water and supplies the Birkenhead steamed out of Simon’s Bay near Cape Town, in the late afternoon of 25th February, with about 634 men, women and children on board. With weather conditions perfect, a clear blue sky and a flat and calm sea, the Birkenhead continued steadily on her passage.

HMS Birkenhead

Captain Salmond, whose family had served in the Royal Navy since the reign of Elizabeth I, had received orders to use all possible haste to reach his destination of Algoa Bay. In order to speed up the trip he decided to hug the South African coastline as closely as possible. This course kept the Birkenhead within approximately three miles of the coast, maintaining a speed of approximately 8 knots.

It was in the early hours of 26th February, approaching a rocky outcrop called Danger Point, some 180 km from Cape Town that disaster struck. With the exception of the duty watch, everyone else was tucked up asleep in their quarters. The watch were scanning the clear glowing waters ahead and the Leadman had just called “Sounding 12 Fathoms” when the Birkenhead rammed an uncharted rock.

The churning paddle wheels of the Birkenhead drove her on with such force that the rock sliced through into the hull ripping open the compartment between the engine-room and forepeak. Water flooded into the forward compartment of the lower troop deck filling it instantly. Hundreds of soldiers were trapped and drowned in their hammocks as they slept.

All the surviving officers and men who could, assembled on deck. Some of the soldiers stood barefoot dressed only in their night-clothes, others less lucky were naked and many with the injuries sustained as they clawed their way from the flooded troop quarters. The senior officer on board, Lieutenant-Colonel Seton of the 74th Royal Highland Fusiliers took charge of all military personnel. He immediately summoned his officers around him and stressed the importance of maintaining order and discipline amongst the inexperienced soldiers.

Distress rockets were fired, but there was no help at hand.

Realising the hopeless position they were in, the captain ordered the lifeboats to be lowered. Much of the lowering equipment would not function, due to a lack of maintenance and a thick layer of paint that clogged the mechanisms.

That night under a clear starry sky the great naval tradition of “women and children first” was established as eventually two cutters and a gig were launched and the seven women and thirteen children were rowed away from the wreck to safety. A 19-year old young ensign of the 74th, Alexander Cumming Russell, was commanded to take charge of the women and children’s cutter and row it to safety.

The horses were cut loose and thrown overboard. Only then did Captain Salmond shout to the men that everyone who could swim must save themselves by jumping into the sea and make for the boats.

Lieutenant-Colonel Seton, a 38-year-old Scotsman and the soldier’s commanding officer, quickly recognised that such a rush would mean that the lifeboats could be swamped and the lives of the women and children onboard would thus be endangered. He drew his sword and ordered his men to stand fast. The untried soldiers did not move even as the ship split in two and the gallant company slipped down into the waves.

The Sinking of HMS Birkenhead

The Birkenhead sank only twenty-five minutes after she had struck the rocks, only the topmast and sailcloth remained visible above the water with about fifty men still clinging to them. The sea was full of men desperate for anything that could float. Death by drowning came quickly to many of them, but the more unfortunate were taken by the Great White sharks.

Witnessing the horror that surrounded them, the women in the cutter pleaded with Ensign Russell to row back towards the struggling men. This he reluctantly did, however none of the soldiers would accept any of the help being offered to them… the had had their orders! One family recognised their father amidst the crashing waves, however he too refused to approach. Seeing their distress Ensign Russell jumped into the water and helped the man into cutter before striking out for the safety of the shore. He barely made 20 strokes before he disappeared from sight, taken by the sharks.

One young officer did manage the three mile swim to the shore where he emerged to find his own horse standing waiting for him.

The next morning the schooner Lioness reached the lifeboats rescuing those onboard, after which she headed for the scene of the disaster reaching the wreck that afternoon, picking up the remaining survivors. Of the 634 people onboard the Birkenhead, only 193 were saved.

Rudyard Kipling immortalised the silent heroes when he wrote:

‘To stand and be still

to the Birken’ead Drill

is a damn tough bullet to chew’.

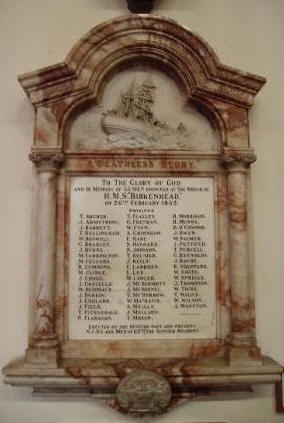

On the wall of St Mary’s Church in Bury St Edmunds is a memorial to the men of the Suffolk Regiment who were lost in the HMS Birkenhead disaster of 1852:

The history of the 74th records the action of the brave men aboard the HMS Birkenhead that fateful day… ‘sheds more glory upon those who took part in it than a hundered well-fought battles’.

Historic UK would like to thank; The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers Museum (Warwickshire), St. John’s House, Warwick, for their help in researching this article; and St Mary’s Church, Bury St Edmunds.

Published: 11th April 2015.