Richard Arkwright, born in 1732 in Preston, Lancashire, is known as “the father of the modern industrial factory system”. He is certainly one of the giants of the age of industrialisation, a man whose inventive mind and innovative approach to business would dramatically change the way people in Britain worked and lived.

Arkwright, the son of a tailor, was born into a large family of thirteen, becoming the youngest of seven surviving children. His parents couldn’t afford to send him to school, so he was taught the basics of reading and writing by his cousin Ellen. After apprenticeship to a wigmaker and barber, an important and potentially very lucrative trade in an age of fashionable wigs, hair-dos, powdering and coiffing, Arkwright set up his own shop in Bolton, near Manchester.

Arkwright’s first marriage was in 1755, to Patience Holt. Their son Richard Arkwright was born soon afterwards, followed by the death of Patience in 1756 when her husband was still just 24. Five years later, Arkwright married Margaret Biggins. The couple had three children. Their daughter Susannah was the only one of the three to reach adulthood.

Wealth coming in from his second marriage enabled Arkwright to expand his business, and it was at this point that his innovative entrepreneurial spirit began to emerge. He obtained a secret recipe for a waterproof dye for colouring hair that gave him a lead over competitors.

The cotton industry had begun in Tudor times in and around Manchester and Bolton, brought in by refugees from the Netherlands who introduced a type of coarse cloth called fustian, made from a mixture of cotton and linen. Arkwright’s trade involved journeying around the country to purchase hair for wig-making, and this gave him an opportunity to observe and talk to the many spinners and weavers who were scattered throughout what was still a largely rural area. It would seem likely that Arkwright’s interest in developing carding and spinning machinery for processing raw cotton into threads began at this time.

Until the 18th century, spinning and weaving were cottage industries in which whole families were engaged, producing the materials by hand with spinning wheels and hand weaving looms. Sometimes individuals would be in business for themselves, but more often merchants would arrange for the raw materials to be brought to the workers’ homes. Once the cloth was complete, it would be collected for selling on.

Commercial cloth-making, particularly woollen cloth, had always played a major part in the establishment of Britain as a wealthy nation, since most of the raw and finished materials could be produced throughout England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland, which was the main source of flax and linen.

Cloth was not simply a commercial product; it had symbolic and even political significance. To this day the Chancellor’s seat in the House of Lords is known as the Woolsack. Any changes to Britain’s cloth trade could have serious consequences for the country. James VI/I had become embroiled in a major scandal over the legislation of cloth and clothiers in the early 16th century. Arkwright would be instrumental in radically changing the way cotton and other cloth was produced and distributed in Britain, bringing about immense social and economic changes.

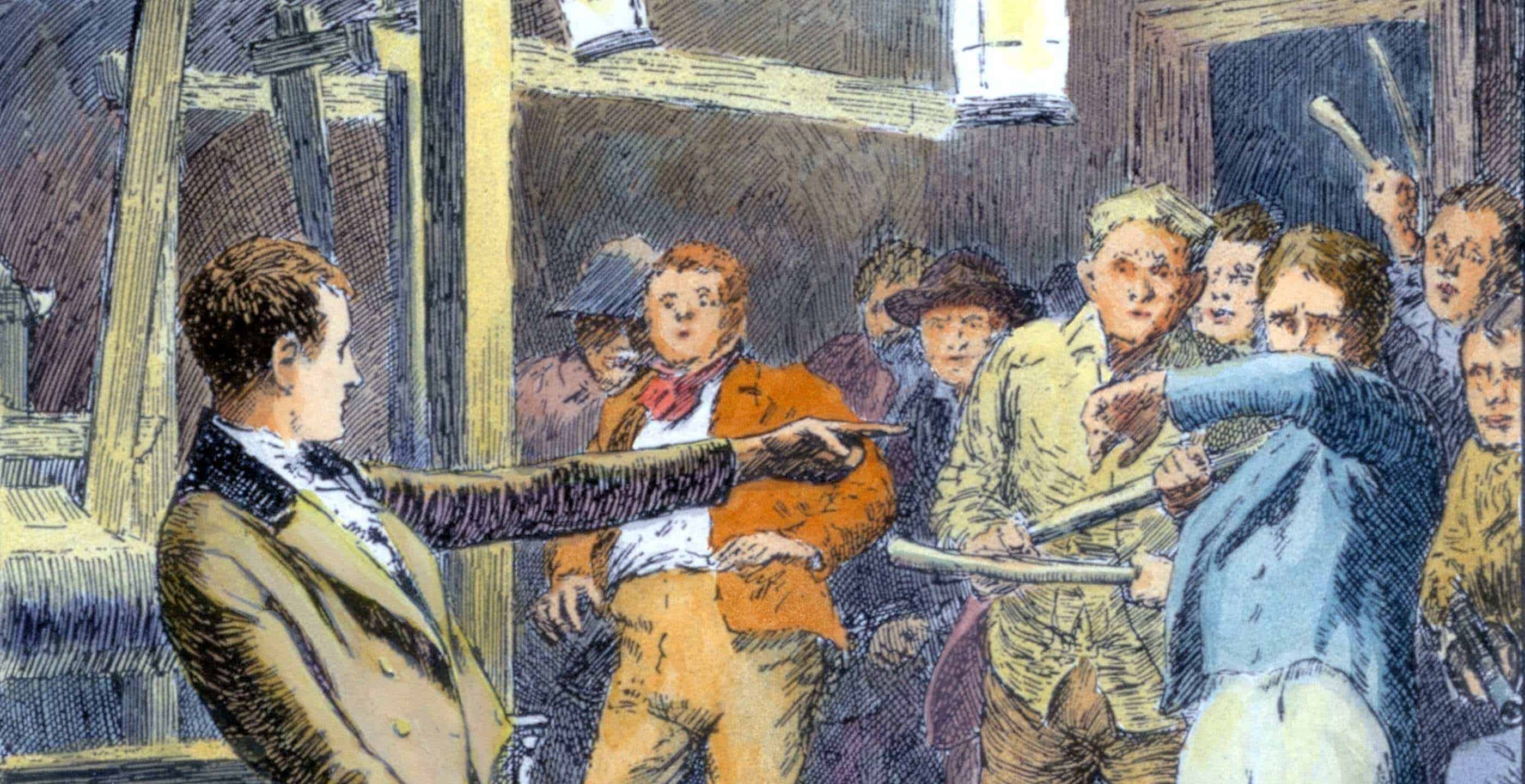

Arkwright was not the only person looking at ways to make spinning more efficient. John Kay, an engineer and clockmaker from Bury in Lancashire, had invented the flying shuttle in 1733, a device intended to speed up the spinning process. Twenty years later, this resulted in the destruction of his house by a mob of angry people, fearful of the loss of their work and incomes. Another inventor, James Hargreaves, used Kay’s flying shuttle design in his “Spinning Jenny” in 1764, which he patented in 1770. In 1768 he too had his house destroyed.

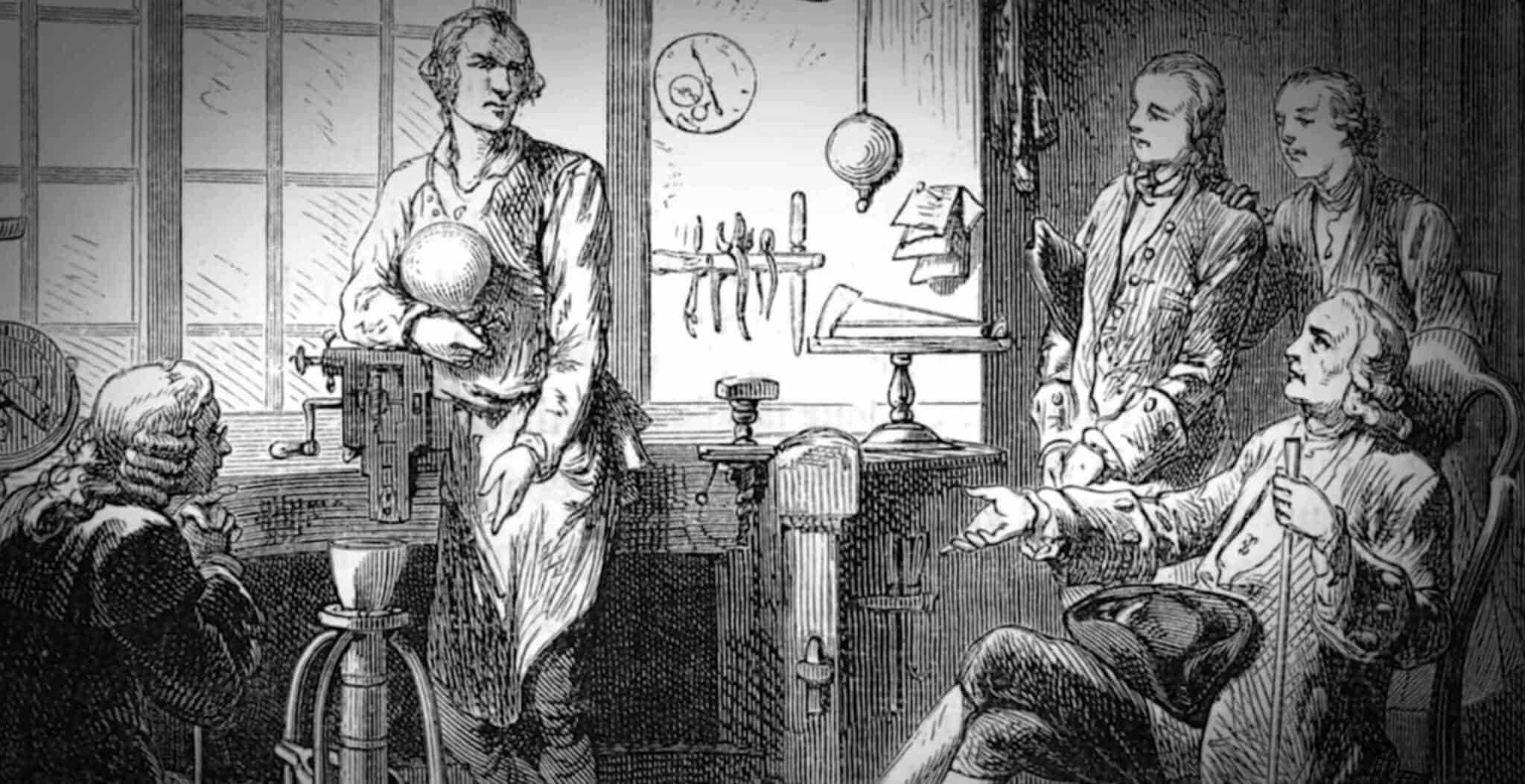

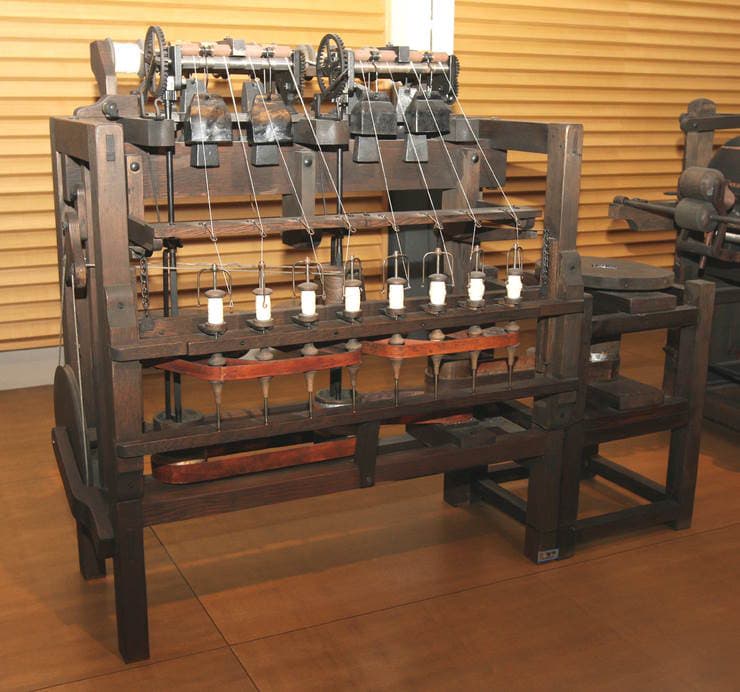

The same year, Arkwright and Kay were working on a new spinning machine in rented rooms in Preston. As a result of the collaboration, Arkwright patented his “spinning frame” in 1769. From this first small-scale horse or water-powered version, which used wooden and metal cylinders to produce strong twisted threads, would arise the massive machines, powered by water and later steam, that would make north-west England a world leader in cotton-spinning. However, Kay had previously been in the employment of one Thomas Highs, and the collaboration between Arkwright and Kay would have far-reaching consequences for Arkwright as a result of Kay’s previous employment.

Arkwright was also working on ways to improve the efficiency of carding cotton. He used a carding machine invented by Lewis Paul in 1748 as the basis for his own improved version, enabling him to take out a patent for a new carding machine in 1775.

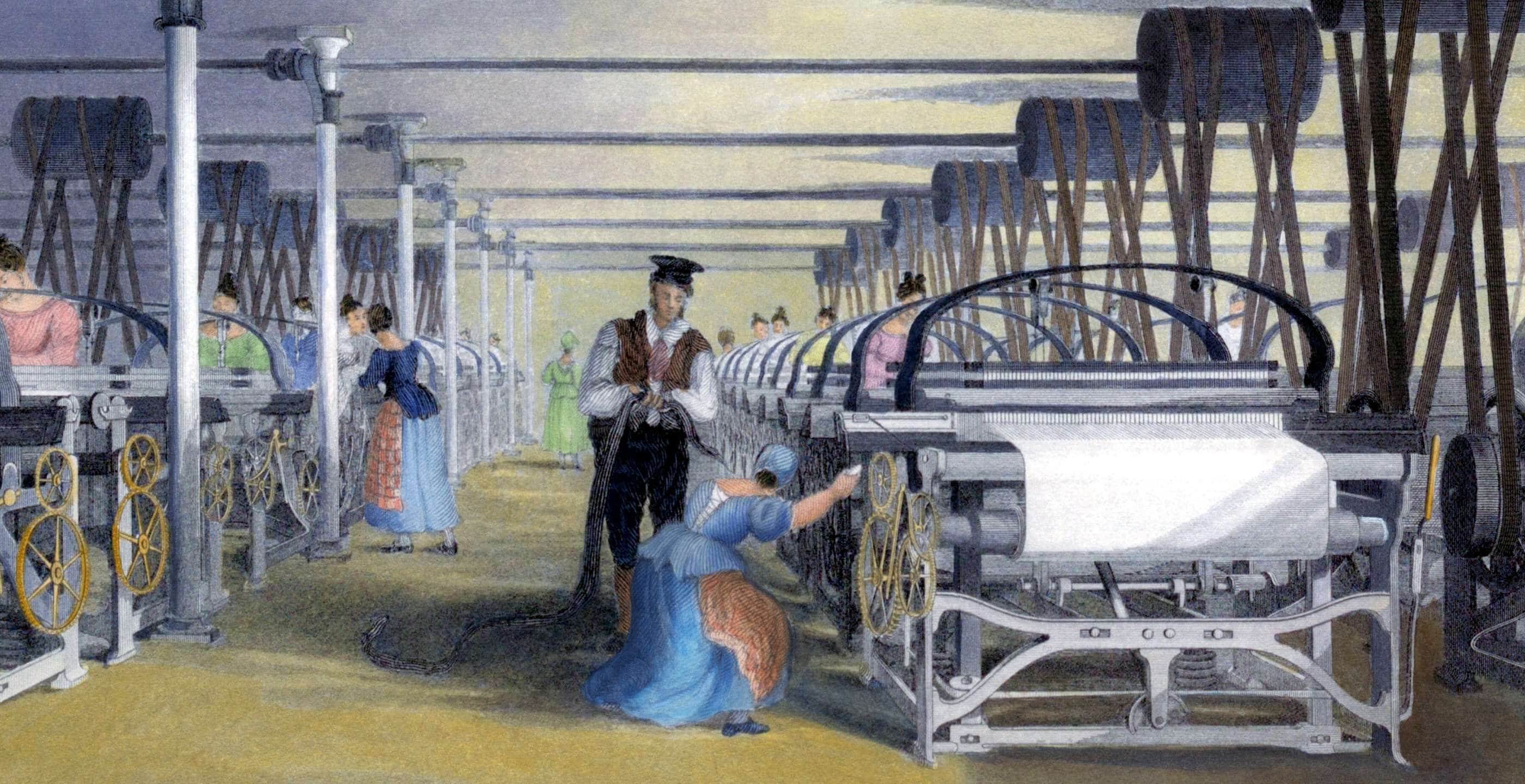

With new and efficient machinery under the control of his own patents, Arkwright was ready for the next stage: the establishment of the first factories for producing cotton thread. His first factory, built in partnership with John Smalley, was in Nottingham, traditional home of fine lace and hosiery. The factory used horse power to drive the new machines.

Wanting to expand, Arkwright went into partnership with hosiery manufacturers Jedediah Strutt and Samuel Need. With Strutt and Need’s wealth, the partners created the first ever water-powered cotton mill in Crompton, Derbyshire. Here the workforce of 200 was employed in both carding and spinning cotton. The workers now lived close by their place of work, with amenities to hand in the same location. Britain’s factory system had begun.

Arkwright used his mill “template” to create more mills throughout the north west. Lancashire’s cool, damp climate proved ideal for the production of cotton threads. In 1775, well on the way to great wealth, Arkwright applied for and obtained a “grand patent” intended to maintain his leading position in a cotton industry that was expanding at speed.

However, public feeling was against him having entire control over an industry through his patents. As is often the case, this attempt by Arkwright to keep his rights over his inventions resulted in long drawn-out court proceedings that only finally came to an end in 1785. In the end, Arkwright lost. Part of the case against him was that he hadn’t actually invented his spinning frame. That was attributed to John Kay, or possibly Kay’s previous employer Thomas Highs.

Arkwright was far from finished, though. Always a visionary when it came to powering his machinery, he was the first to install a James Watt designed steam engine, in one of his mills in Derbyshire. It was not used to power the mill equipment though, rather to pump water into the millpond for the waterwheel. He remained active in the establishment of mills throughout the land, helping David Dale to establish cotton mills in New Lanark, Scotland.

Arkwright gained his knighthood in 1786 and was High Sheriff of Derbyshire in 1787. When he died in 1792, he left a fortune of £500,000. His legacy can be witnessed by visiting any number of mill towns in the north of England and Scotland.

Arkwright left his mark not only economically, but also socially, environmentally and architecturally. By the late 19th century, Lancashire was a county of smoking mill chimneys with workers’ terraced housing spreading out around them, rather than a rural landscape in which home workers spun and wove cloth.

The archetypal “self-made man” of the Industrial Revolution, Arkwright’s own treatment of his workers was partly paternalistic, partly exploitative. The nation gained efficiency at the price of workers’ independence. He was instrumental in establishing steam as a practical mode of power for mills. He provided inspiration for others to develop their own ideas, including Samuel Crompton’s spinning mule, literally a cross between Arkwright’s water frame and Hargreaves’ Spinning Jenny.

Arkwright was one of the highly successful leaders of industrialisation and even his success came at the price of litigation and destruction. His mill at Birkacre was one of those destroyed in the anti-machinery riots of 1779. Other men such as Kay and Hargreaves, whose contributions are less well-known, often suffered rather than benefitted from their ideas.

The growth of the Lancashire cotton industry was also dependent on cotton produced by enslaved people in the cotton fields of the southern states of America. By 1820, three-quarters of the cotton imported into Britain came from American plantations. Much of that was destined for Lancashire mills.

Richard Arkwright’s legacy is far-reaching and complicated, and the effects are still being felt to this day. Britain’s industrial inheritance is just as important and challenging as its political and military history. This rich, complex heritage is due in no small part to Richard Arkwright.

Dr Miriam Bibby is a historian, Egyptologist and archaeologist with a special interest in equine history. Miriam has worked as a museum curator, university academic, editor and heritage management consultant.

Published: 22nd March 2023.