There have always been fashion ‘tribes’, from fops and beaux, bucks and dandies to Goths and punks, but the ‘macaronis’ of the 1760s and 1770s exceeded them all in their dedication to excess and ostentation.

In the mid-1760s, Europe had opened up again to English travellers following the end of the Seven Years’ War. Aristocratic young men returning from their ‘Grand Tour’ to Italy and France began to appear in London dressed in a distinctive, extravagant style that derived from French court dress. Their predilection for foreign food as well as fashion earned them the nickname of ‘macaronis’.

The term first appears in a letter written by the writer and wit Horace Walpole in 1764, in which he refers to the ‘Maccaroni Club’ – thought to be Almack’s – as the place where ‘all the travelled young men who wear long curls and spying-glasses’ gathered.

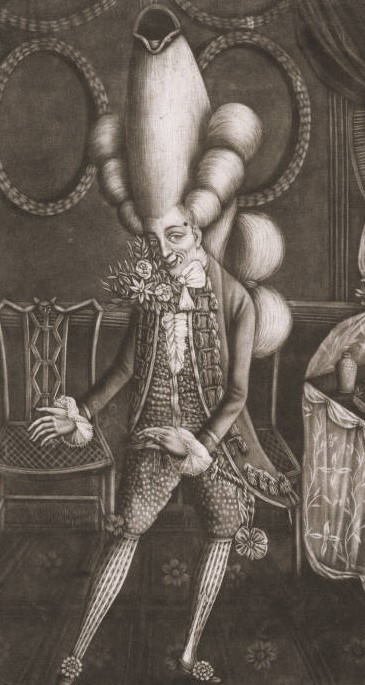

The macaroni ‘uniform’ included a slim, tight-fitting jacket with waistcoat and knee-length breeches, all made of silk or velvet in bright colours, and heavily embellished with delicate embroidery and lace. Patterned stockings and shoes with large diamond or paste buckles and high red heels were de rigeur.

The correct accoutrements were crucial: Walpole had mentioned the quizzing glass or ‘spying-glass’, but other accessories included an enormous nosegay in the buttonhole of the jacket, oversized buttons, and numerous fobs, seals and watches hanging on chains. George FitzGerald, a nephew of the Earl of Bristol and a dedicated macaroni, carried egotistical display to its limits by wearing a miniature painting of himself pinned to his chest.

The defining feature of the macaroni look was the hairstyle. Almost all men wore curled and powdered wigs in the eighteenth century: it was estimated that in George III’s reign the British army used 6,500 tons of flour every year for wig powder. The macaronis were famous – or infamous – for their ‘high hair’.

The front part of the wig was brushed up vertically into a crest, jutting up to nine inches above the head, with side rolls and a thick ‘club’ of hair hanging down the back, tied with a black ribbon bow or confined in a ‘wig bag’.

Women in the 1770s also wore ‘high hair’, often adding tall plumes to their coiffures to increase the height even further. Walpole referred to these ultra-fashionable women as ‘macaronesses’, but the term did not catch on.

Dress had long been an indicator of social class in England, as in many other countries. In the Middle Ages, sumptuary laws defined who could and who could not wear certain items of clothing. These laws were repealed in the seventeenth century, and by the late eighteenth century, with the spread of wealth down the social scale, the middling and lower classes began to aspire to dress fashionably. This aroused social anxiety: if servants and apprentices dressed like their employers, how could the distinctions of rank be maintained?

The writer Tobias Smollett commented in his popular novel of the time, Humphry Clinker, that ‘The gayest places of public entertainment are filled with fashionable figures; which, upon enquiry, will be found to be journeymen taylors, serving men and abigails, disguised like their betters. In short, there is no distinction or subordination left’.

The Gentleman’s Magazine of September 1771 derided ‘that pitiful ambition which stirs up the common people to ape their superiors’, in this case a hosier who had appeared at Ranelagh, the smartest of London’s pleasure gardens, ‘with his sword, bag, and embroidered habiliments’ and had ‘strutted around … with all the importance of a Nabob’. Wearing a sword was considered the privilege of a gentleman, given its association with the court, and ‘this upstart’ was challenged by some ‘justly indignant’ bystanders, who showed him ‘the nearest way out of the room with some kicks in the posterior’.

It took skill to manage a sword, as the painter Richard Cosway discovered when he was deputed to show the Prince of Wales, later George IV, around the annual Royal Academy exhibition. The young Prince of Wales was a follower of fashion himself. When he took his seat in the House of Lords in 1783, he was dressed for the occasion in black velvet embroidered in gold and lined with pink satin, and shoes with matching pink heels.

Cosway was a short man, who had the reputation of being both a social climber and a macaroni. The royal fencing master, Henry Angelo, described the scene in the Academy in his memoirs: Cosway, dressed in ‘a dove-coloured, silver-embroidered court dress, with the concomitants—sword, bag, and chapeau bras’, followed the Prince through the halls, ‘uttered a hundred high-flown compliments, and strutted on his scarlet heels, as important in his own estimation, as any newly created lord’.

When the Prince got into his carriage to leave, Cosway ‘retreated backwards, with measured steps, making at each step a profound obeisance … [he] bent himself with such magnificent circumflexion of his little body, that, his sword getting between his legs, tripped him up, and he was suddenly prostrate in the mud.’ The Prince, watching from his coach window, exclaimed gleefully, ‘Just as I had anticipated, ye gods!’

In the late 1770s, Britain was fighting to retain control of the American colonies – a struggle which many people in Britain saw as a civil war. The revolt was a severe shock to the national psyche, and aroused fears that Britain had become decadent, its national spirit ruined by luxury and self-indulgence. The macaronis, with their obsession with fashion and appearance, were an obvious target for this anxiety. The new fashions were attacked in the newspapers, and became a favourite subject of the popular satirical prints of the time.

Macaronis were castigated as ‘un-English’ and ‘unmanly’. The French influence on their fashions was deplored: the London Magazine complained that ‘the appearance of a Frenchman … which formerly set every Englishman a laughing, is now entirely adopted in this country’, adding ‘who can see, without indignation, a parcel of powdered baboons bowing and scraping at one another ….’.

The outcry, like the macaroni style itself, was short-lived. By the 1790s, men had begun to abandon the brightly coloured and embroidered silks and velvets, the lace and high heels that had characterised eighteenth century fashion. After a tax on hair powder was introduced in 1795, wigs finally went out of fashion.

The macaroni craze was the last explosion of colour and extravagance in men’s dress before the arrival of the more sober, pared-down style that was championed by Beau Brummell at the beginning of the next century, and that was to set the standard for modern men’s clothing.

By Elaine Thornton. I am an amateur historian, and the author of a biography of the opera composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, ‘Giacomo Meyerbeer and his Family: Between Two Worlds’ (Vallentine Mitchell. 2021). I am currently researching the life of the Georgian newspaper editor and journalist Sir Henry Bate Dudley.

Postscript: The lyrics of the popular song, Yankee Doodle Dandy, refer to the Macaroni craze:

Yankee Doodle went to town,

Riding on a pony.

He stuck a feather in his cap.

And called it macaroni.

Apparently the first version of Yankee Doodle Dandy was written by the British during the French and Indian Wars in order to make fun of the colonial ‘Yankees’; ‘doodle’ meaning simpleton and ‘dandy’ meaning a fop. The song infers that the Yankee Doodle was silly enough to think he could become fashionable and upper class (like the Macaronis in Britain), merely by putting a feather in his cap. The song was later appropriated by the Americans as a song of defiance during the Revolutionary War, adding verses to mock the British.

Published 16th February 2023