Over the centuries, inspiration for fashion has come from a variety of places, but with the growth of literacy and the increasing popularity of broadside ballads, penny dreadfuls and newspapers over the 18th and 19th centuries, an ever-growing number of ordinary people found their fashion choices influenced by newsworthy people as well as fictional characters. This was perhaps the precursor to today’s obsession with gossip magazines, where we are told how to dress like D-list celebrities; but it also reflects our ancestors’ macabre interest in murderers and unpleasant characters who could make or break a fashion.

In the 19th century people tended to romanticise murders, especially when they involved young women. Judith Flanders in The Invention of Murder writes of how the apparent ‘rarity value’ of such murders grabbed the imagination, with broadside writers, ballad singers and newspaper reporters glamorising those involved. Maria Marten, victim in the notorious ‘Red Barn’ case of 1827, was converted from mother of illegitimate children to innocent young woman by the press coverage she received.

A picture of Maria Marten who was shot dead by her lover, William Corder in 1827. The pair had planned on eloping to Ipswich until Corder decided to shoot her dead at their secret rendezous at the infamous ‘Red Barn’ in Polstead, Suffolk.

The case of Miss Bell, a young woman found murdered on the seashore at Scarborough in May 1804, also excited the public imagination. Her father blamed the ‘fashion’ among Scarborough girls to be escorted around town by army officers stationed there. His daughter, attracted by the uniform of the York Volunteers, allowed herself to be wooed by one of their number who subsequently murdered her. The Hull Packet newspaper noted the fact that some time after the event, the public was ‘still much interested in the fate of Miss Bell’ (10 July 1804), her meeting with the soldier murderer romanticised by locals.

Later under Queen Victoria, the criminal justice system changed substantially. Martin Doyle was the last man executed for attempted murder on 27 August 1861 – the Criminal Law Consolidation Act of that year limited the death penalty to murder, embezzlement, piracy and high treason. But until 1868, executions were still public events. Men, women and children would all attend a hanging for a day out, so it is unsurprising that murder cases could influence fashion.

For example, in 1864 there was a notorious murder case – that of Hackney banker’s clerk Thomas Briggs, who claimed the dubious title of being the first man to be murdered on Britain’s railways. Briggs was attacked and thrown out of his railway carriage one evening as he returned from work in the city to his home in Hackney. When his carriage was later inspected it was found to be empty apart from bloodstains and a man’s hat left on a seat. It wasn’t Briggs’ hat – conversely, it was the only clue to the identity of his murderer.

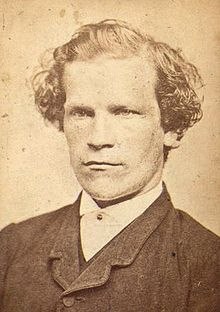

The hat was alleged to have belonged to a German tailor, Franz Muller (pictured to the right), who had cut the item down to make a shorter, somewhat squashed accessory. The hat was linked directly to him and helped convict him of Briggs’ murder, with the Metropolitan Police embarking on a transatlantic chase to catch Muller, who had fled to New York.

The hat was alleged to have belonged to a German tailor, Franz Muller (pictured to the right), who had cut the item down to make a shorter, somewhat squashed accessory. The hat was linked directly to him and helped convict him of Briggs’ murder, with the Metropolitan Police embarking on a transatlantic chase to catch Muller, who had fled to New York.

Despite Muller’s conviction and his subsequent execution, his notoriety caught the public’s imagination and his hat became a brief fashion trend. Those who copied him in having their hats cut down in size were said to have ‘mullered’ them.

An earlier murder case, however, had the opposite effect on fashion.

In 1849 the newspapers filled their pages with coverage of the so-called ‘Bermondsey Horror’ case. A married couple, Frederick and Maria Manning , were convicted of murdering Maria’s former lover, Patrick O’Connor, and burying him under the floor of their kitchen at 3 Miniver Place, Bermondsey.

After the murder, they both fled, separately. Maria (pictured to the right) was tracked down to Edinburgh, her husband to Jersey. Maria – a haughty woman with delusions of grandeur – was originally from Switzerland. She had been in service to very wealthy, respectable households, and believed herself to be every bit a part of society as they. She therefore dressed as befitted a society lady: carefully and immaculately.

After the murder, they both fled, separately. Maria (pictured to the right) was tracked down to Edinburgh, her husband to Jersey. Maria – a haughty woman with delusions of grandeur – was originally from Switzerland. She had been in service to very wealthy, respectable households, and believed herself to be every bit a part of society as they. She therefore dressed as befitted a society lady: carefully and immaculately.

On the day of her execution, 13 November 1849, she walked to the scaffold outside Horsemonger Lane Gaol in Southwark, dressed in a black satin gown. This material had been very popular at the time – but when women saw Maria hanged in the dress, or read about it afterwards, they stopped wearing black satin, thus ending a fashion and bringing misery to numerous dressmakers and shops.

The public appetite for glamorous criminals was also reflected in the characters of Victorian novels. Many novelists wrote about crime and criminals, with the perpetrators often being more interesting characters than the law-abiding do-gooders who ensured they met their comeuppance.

Although many of these criminals were male, it was the female baddies, such as Nancy in Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, who really grabbed people’s attention.

Dickens had long been interested in crime and punishment, even attending the execution of Maria Manning. He was filled with horror and the next day wrote a letter to The Times complaining of the lack of emotion and pity shown by the crowds that gathered to watch this ‘general entertainment’.

The memory of the case stayed with Dickens. Three years later he started writing Bleak House and the character of Mademoiselle Hortense – a short-tempered, vengeful French-speaking maid – was based on the murderess.

Eleven years after Manning’s execution, Wilkie Collins referred to her in his sensational novel The Woman in White, showing the enduring fascination the public had with her, although by this time Manning’s chubbiness, which had originally been seen as a sign of affluence and something to aspire to, had become less fashionable.

The strange attraction of murderers was commented on in the press during the 19th century. In 1871, the so-called ‘Stockwell Murder’ – where a Mrs Watson was killed by her husband – was described as a ‘fashionable murder’ by the Huddersfield Chronicle.

It criticised the tendency of the Victorian public to idealise female victims of crime and to sensationalise the events surrounding a murder, and noted the impact of education and refinement on how the public perceived a murderer or murder victim.

In this case again, it was the murderer’s clothes that attracted attention: Mr Watson had removed the bloody wristbands of his shirt in order to wear it after the crime, creating a new, looser-sleeved garment.

The link between fashion and crime continued into the 20th century. During the 1920s, the western world was both attracted and repelled by the tales of gangster lifestyles in the United States. Al Capone and his cohorts, in their smart clothes, fedoras, spats and overcoats, influenced male fashion; their flapper companions, with cloche hats, fur stoles and insouciant expressions, seemed glamorous and beyond the law.

Al Capone mug shot, 17 June 1931.

Whatever was happening in the wider economy, the gangsters seemed immune to it, showing off their wealth with ostentatious jewellery – platinum watch chains, diamond rings – in recognition of the fact that fashion depended as much on well-chosen and preferably expensive accessories as a trendy suit.

The gangster’s large wardrobes showed that consumerism was well and truly part of modern society, and, despite their criminal activities, these men became something to aspire to. The public sought to include an element of this luxurious and expensive lifestyle in their own lives, by way of a natty suit or a beautiful pair of earrings.

Conversely though, some respectable men refused to wear fedoras because of their association with the underworld. Panama hats were more popular, but when Al Capone was pictured wearing one, the choices for those who refused to wear something popularised by criminals were limited further.

In the 1930s, newspaper coverage of Bonnie and Clyde’s exploits rooted them in the fashion consciousness. The slim, attractive Bonnie Parker, photographed draped over a car, grabbed the public’s attention. In her woollen beret, t-bar heels and closely fitted fashionable clothes, she seemed the epitome of bad-girl glamour.

Bonnie and Clude sometime between 1932 and 1934, when their exploits in Arkanas included murder, robbery and kidnapping.

Forty years later, she was still influencing fashion when Faye Dunaway portrayed her on screen. Part of the attraction was that she was a young, pretty girl who proudly posed for photographs with cigar in mouth and gun in hand – a blend of masculinity and femininity. The film link is significant: Elizabeth Carolyn Miller, who has looked at what she describes as the ‘New Woman Criminal’ in depth, says that such characters display and embody ‘a new form of feminine glamour associated with consumer fantasy and the screen culture of the cinema’.

This interest in female criminals and their style has continued into the modern day. In 1974 Patty Hearst gained column inches and notoriety when she was kidnapped and developed Stockholm syndrome, which resulted in her empathising with the political motives of her captors and joining in their criminal activities. The fact that she was young, pretty and pictured in an atypical pose – like Bonnie Parker, in a jauntily arranged beret with M1 carbine gun in hand whilst robbing a bank – ensured that newspaper readers and TV viewers were intrigued and wanted to look like her, even if they had no intention of breaking the law.

The public appetite for these female lawbreakers ignored the real facts of their lives: their personality disorders, psychological problems, poverty or irrational love for the men who sometimes encouraged them to commit crime. It was the romance of the imagined situation that appealed; the ability of these women to appear so glamorous and display such apparent confidence. Perhaps their fans thought that to emulate their dress would instil such confidence in them as well.

This article was originally written for Your Family History magazine.