English history is rife with rebellions, riots, and revolutions. Most often, citizens took to the streets to vocalize their opinions and sometimes took direct action against those who wronged them. But there was more than one way to rebel and let their voices be heard; they could rebel using fashion. Want to stick it to the man in 12th century England? Dare to grow a beard and flaunt it in the face of your enemies!

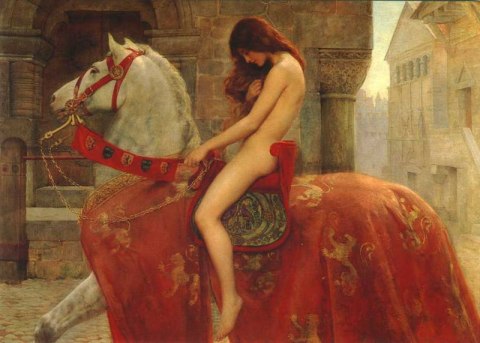

Of course, clothing and accessories are not always successful in their incitement for rebellion, sometimes more is needed to spur others into action, or rather less. In the 11th century Godgifu, or Lady Godiva as she is now known, is said to have made a deal with her husband, that if he lowered his oppressive taxes on the town of Coventry, she would ride through its streets naked. Surprisingly, she called his bluff and did just that, freeing the people of Coventry from their oppression and riding her way into the history books. While this may not have occurred, it does seem very similar to the act of penance, wherein a person who wishes to appeal to God and atone themselves will walk through the streets of their town or city with their hair down and only their chemise to clothe them. It was usually not meant as an act of rebellion, but some have twisted it into a masterful PR move, or defiance against a system.

Even if one is wearing clothing suitable for society, there can be other ways of playing the rebel. When the Normans invaded Anglo-Saxon England in 1066, they brought with them the style of clean-shaven faces and cropped hair. This was in stark contrast to the Anglo-Saxons, who greatly prided themselves on their flowing locks and manly beards. Their style was so ingrained in their society that there were laws against men cutting other men’s beards and hair. The fines for such an act were even greater than for offences such as piercing another man’s throat or removing his fingers. When William the Conqueror created a law forcing Anglo-Saxon men to shave in order to fit society’s new look, they rebelled. They maintained their prideful appearance. The concept was so important to their culture that there were still men in the 12th century sporting the style of pre-Norman Anglo-Saxons.

A king and his witan – from the eleventh-century Old English Hexateuch [British Library]

A king and his witan – from the eleventh-century Old English Hexateuch [British Library]

In the 14th century, the Black Death brought horror and despair to the country, decimating the population and killing millions. It also created a brave new world, where wages were high and workers in demand due to the sudden decrease in population. This spread prosperity amongst the lower classes, and the fashion reflected their newly minted status as wealthy persons of means. Merchants began dressing in expensive, exotic fashion and farmer’s wives strutted around in furs as if they were ladies of the court. This was not so much a rebellion as an emergence. However, it was not seen that way by Edward III, who began to pass a series of “sumptuary laws” to regulate the fashion of the people. To him, there should be visible markings of a person’s class and role in society. Prostitutes, for instance, were made to wear striped hoods to denote their role. Merchants could no longer wear exotic imports thereby keeping the textile industries of England prosperous and regulating the style of Englishmen into a cohesive unit. Of course not everyone followed the rules, as we will later learn.

Unpopular rulers or unpopular rules always faced rebellion to some degree. For those in positions of power, it was imperative to remember that common folk were responsible for the rise and fall of many figures in society. Sometimes it was even more dangerous to rebel against them than against the powerful ruling class.

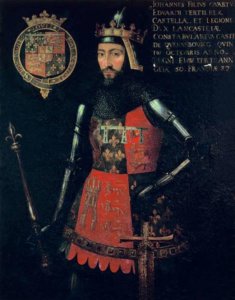

John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt

One such figure who learned this the hard way was Sir John Swinton, who worked for John of Gaunt at a time when he was highly unpopular. In 1377 Swinton disregarded the people’s feelings towards Gaunt and paraded through the streets of London wearing John of Gaunt’s dashing livery badge on his collar to let everyone know how proud he was to work for him.

This did not turn out well for him. The badge was spotted immediately and a mob began to form. Swinton was subsequently dragged off his horse, his badge ripped from his collar, and he began to receive the beating of his life. At the last moment the Mayor of London, hearing of the commotion, intervened and saved Swinton from what would have been a grisly fate.

While it might seem that sumptuary laws would disappear once order was restored after the chaos of the 1300s, this was not the case. Tudor rulers saw great value in them, being able to control the population and remind them to stay within their station. However, with such strict rules, it was only natural that some would seek to rebel in an effort to show off their assets. These regulations lasted well into the 17th century, so there was plenty of opportunity to rebel. There were instances of people rebelling discreetly, such as a fellow of King’s College who was sent to prison in 1576 for wearing Greek style breeches underneath his attire. There were also people who flagrantly disregarded the rules, such as a servant who was arrested for wearing “a very monsterous and outraygous greate payre of hose”. This has been assumed to be a result of overstuffing his stockings beyond the maximum 1 ¾ yard of padding allowed for servants, apprentices and students.

The laws continued to regulate English citizens, even overseas. Many early leaders in colonial America attempted to create laws governing fashion, such as a 1651 law in Massachusetts which imposed a 10 shilling fine to anyone who wore “any gold or silver lace, or gold and silver buttons, or any bone lace above 2s. per yard, or silk hoods, or scarves” if their estate did not exceed 200 pounds. By the time of the 18th century, however, rebellious fashion was not the most pressing issue. With the advent of the American Revolution, any remaining sumptuary laws went out the window and with them went the European style. Most Patriots adapted a simplistic style in stark contrast to the fussiness of the Europeans. Benjamin Franklin often sported the simple style of an American Quaker, and let his natural hair fall loose around his face, rather than hidden beneath a powdered wig. This not only rebelled against the ruling fashion of the English around him, but set him apart from his Loyalist neighbours by portraying what he thought the ideals of America should be: honest and direct.

Benjamin Franklin wearing a silk suit at the French court c. 1778

Benjamin Franklin wearing a silk suit at the French court c. 1778

Throughout history these outward appearances were in literal opposition to their society, and manifested what the rebels truly felt in their hearts. They have incited riots, provoked change and reinforced personal beliefs all without uttering a word. Sometimes, fashion can send the loudest message of all.

Laura Walls is a historian and writer, having received her MA in Museum Studies from Kingston University. She has previously worked for the National Trust and at the Tower of London, as well as various other historic sites in the UK and US.