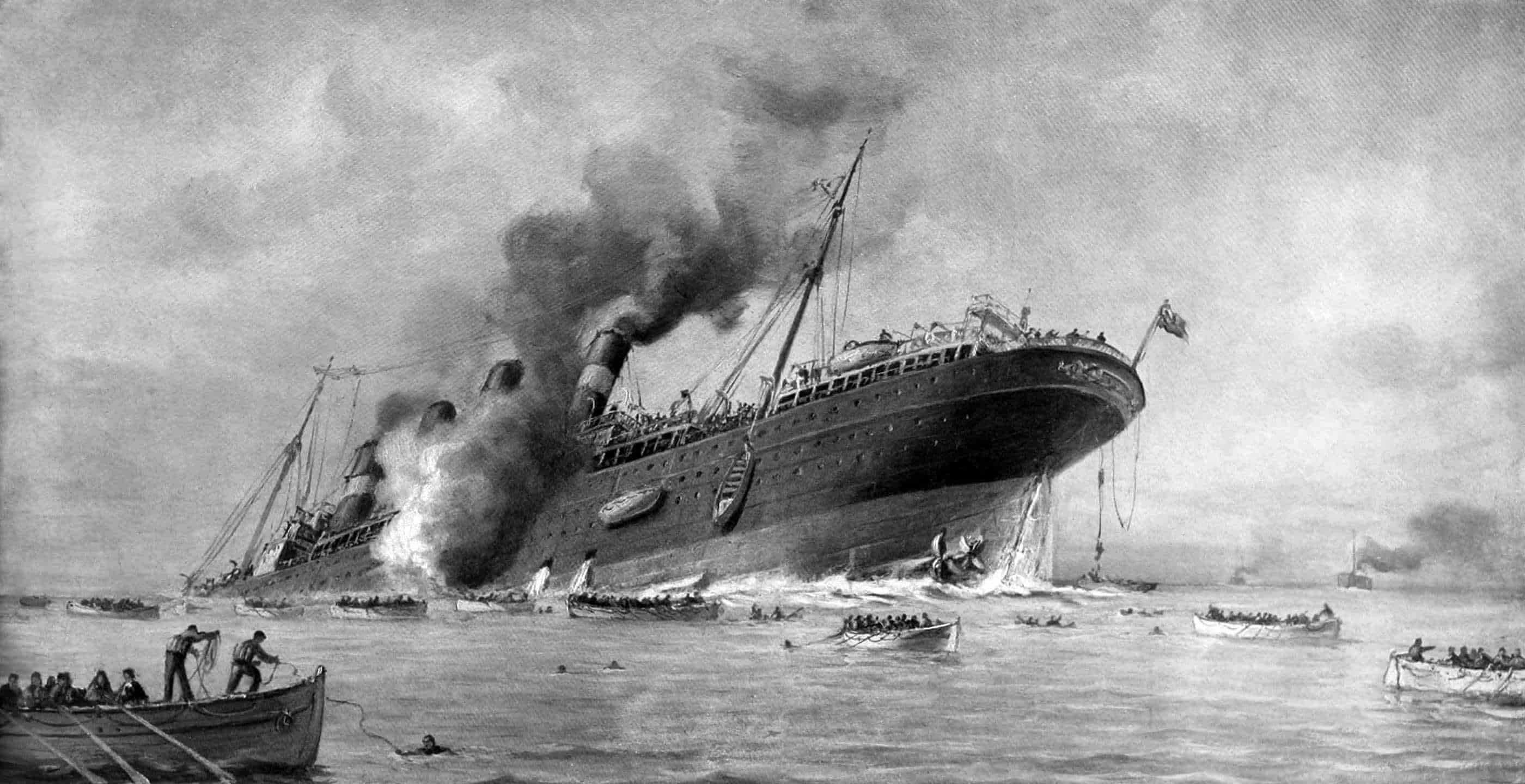

It can be argued that no single event in history has sparked more worldwide fascination than the sinking of the RMS Titanic. The story is ingrained in popular culture: the largest, most luxurious ocean liner on the planet strikes an iceberg during its maiden voyage, and, without an adequate number of lifeboats for all on board, sinks to the abyss with the lives of over 1,500 passengers and crew. And while the tragedy still captures people’s hearts and minds over a century later, no other individual within the narrative is source for more controversy than that of J. Bruce Ismay.

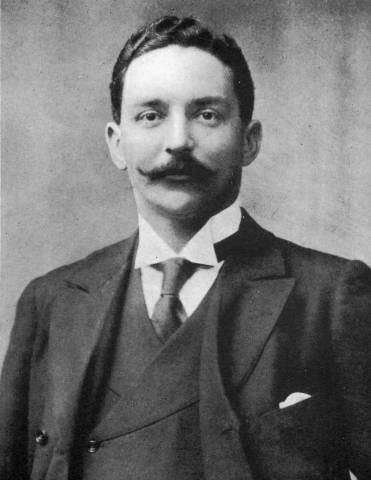

Ismay was the esteemed chairman and managing director for The White Star Line, the Titanic’s parent company. It was Ismay that ordered the construction of the Titanic and her two sister ships, the RMS Olympic and RMS Britannic, in 1907. He envisaged a fleet of ships unparalleled in size and luxury to rival their faster Cunard Line competitors, the RMS Lusitania and RMS Mauretania. It was normal for Ismay to accompany his ships during their maiden voyages, which is exactly what happened in regards to the Titanic in 1912.

The events that follow are often depicted rather unfairly, and the result is that most people are familiar with only one, biased impression of Ismay – that of an arrogant, selfish businessman that demands the captain increase the ship’s speed at the expense of safety, only to later save himself by jumping into the nearest lifeboat. However, this is only partly true and neglects to depict many of Ismay’s heroic and redeeming behaviour during the disaster.

Due to his position within The White Star Line, Ismay was one of the first passengers to be informed about the grievous damage the iceberg had dealt the ship – and nobody understood the precarious position they were now in better than Ismay. After all, it was he who had reduced the number of lifeboats from 48 to 16 (plus 4 smaller ‘Collapsible’ Engelhardt boats), the minimum standard required by the Board of Trade. A tragic decision that must have weighed heavily on Ismay’s mind that cold April night.

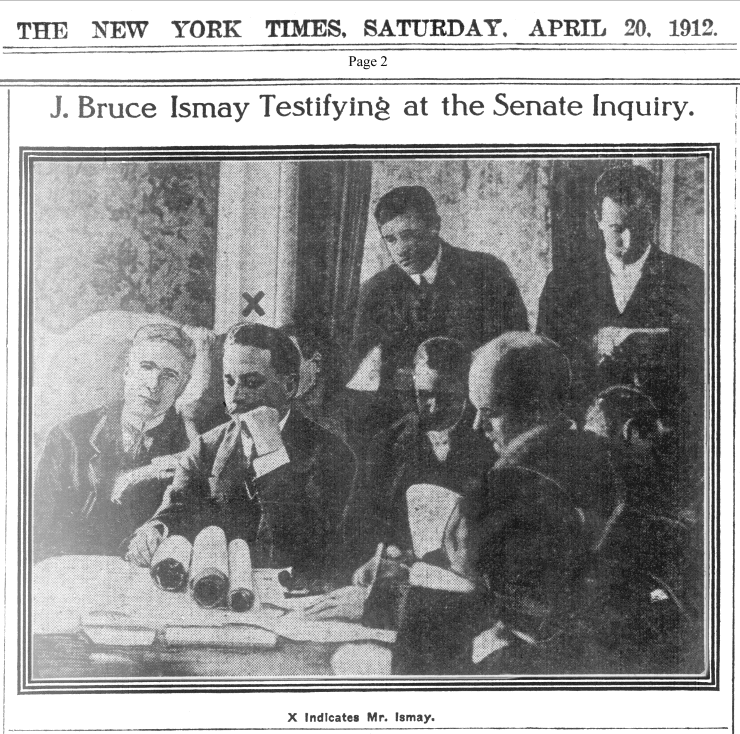

Nonetheless, Ismay is reputed to have assisted crewmen in preparing the lifeboats before helping women and children into them. “I assisted, as best I could, getting the boats out and putting the women and children into the boats,” Ismay testified during the American inquiry. Convincing passengers to abandon the warm comforts of the ship for the cold, hard boats must have been a challenge, especially as it was not immediately evident that there was any danger. But Ismay used his rank and influence to usher potentially hundreds of women and children to safety. He continued to do so until the end was near.

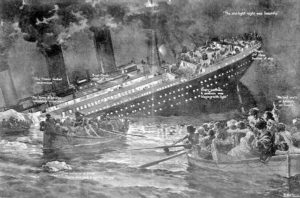

After it became increasingly clear that the ship would sink before help arrived, and only after checking there were no more passengers nearby, Ismay finally climbed into Engelhardt ‘C’ – the last boat to be lowered using the davits – and escaped. Around 20 minutes later, the Titanic crashed beneath the waves and into history. During the ship’s final moments, Ismay is said to have looked away and sobbed.

On board the RMS Carpathia, which had come to the rescue of the survivors, the weight of the tragedy had already begun its toll on Ismay. He remained confined to his cabin, inconsolable, and on the influence of opiates prescribed by the ships doctor. When stories of Ismay’s culpability began to spread among the survivors on board, Jack Thayer, a first-class survivor, went to Ismay’s cabin to console him. He would later recollect, “I have never seen a man so completely wrecked.” Indeed, many on board sympathised with Ismay.

But these sympathies were not shared by vast swathes of the public; upon arriving in New York, Ismay was already under heavy criticism by the press on both sides of the Atlantic. Many were outraged that he had survived while so many other women and children, especially among the working class, had died. He was branded a coward and received the unfortunate nickname of “J. Brute Ismay”, among others. There were many tasteless caricatures depicting Ismay abandoning the Titanic. One illustration shows a list of the dead on one side, and a list of the living on the other – ‘Ismay’ being the only name on the latter.

It is a popular belief that, hounded by the media and plagued with regret, Ismay retreated into solitude and became a depressed recluse for the rest of his life. Although he was certainly haunted by the disaster, Ismay didn’t hide from reality. He donated a significant sum to the pension fund for widows of the disaster, and, instead of avoiding responsibility by stepping down as chairman, helped pay out the multitude of insurance claims by the victim’s relatives. In the years following the sinking, Ismay, and the insurance companies he was involved with, paid out hundreds of thousands of pounds to victims and relatives of victims.

However, none of Ismay’s philanthropic activities would ever repair his public image, and, from retrospect, it is easy to understand why. 1912 was a different time, a different world. It was a time when chauvinism was common and chivalry was expected. Until World War I shook the world’s perspective on such matters, men, as the presumed superior race, were expected to sacrifice themselves for women, their country, or the ‘greater good.’ It seems that only death would have saved Ismay’s name, for he was in an especially unfortunate position compared to most other men on board the Titanic: not only was he a wealthy man, but he held a high-ranking position within The White Star Line, a company many people held accountable for the disaster.

But things have changed a lot since 1912, and the evidence in Ismay’s favour is undeniable. So, in an age of social progression, it is unforgivable that modern media continues to perpetuate Ismay as the villain of the Titanic narrative. From Joseph Goebbels Nazi rendition, to James Cameron’s Hollywood epic – nearly every adaptation of the disaster casts Ismay as a despicable, selfish human. From a purely literary standpoint, it does make sense: after all, a good drama needs a good villain. But this not only propagates antiquated Edwardian values, it also serves to further insult the name of a real man.

The shadow of the Titanic disaster never stopped haunting Ismay, the memories of that fateful night never far from his mind. He died from a stroke in 1936, his name irreparably tarnished.

James Pitt was born in England and currently works in Russia as an English teacher and freelance proofreader. When he isn’t writing, he can be found going for walks and drinking copious amounts of coffee. He is the founder of a small language learning website called thepittstop.co.uk

Published: January 22, 2021.