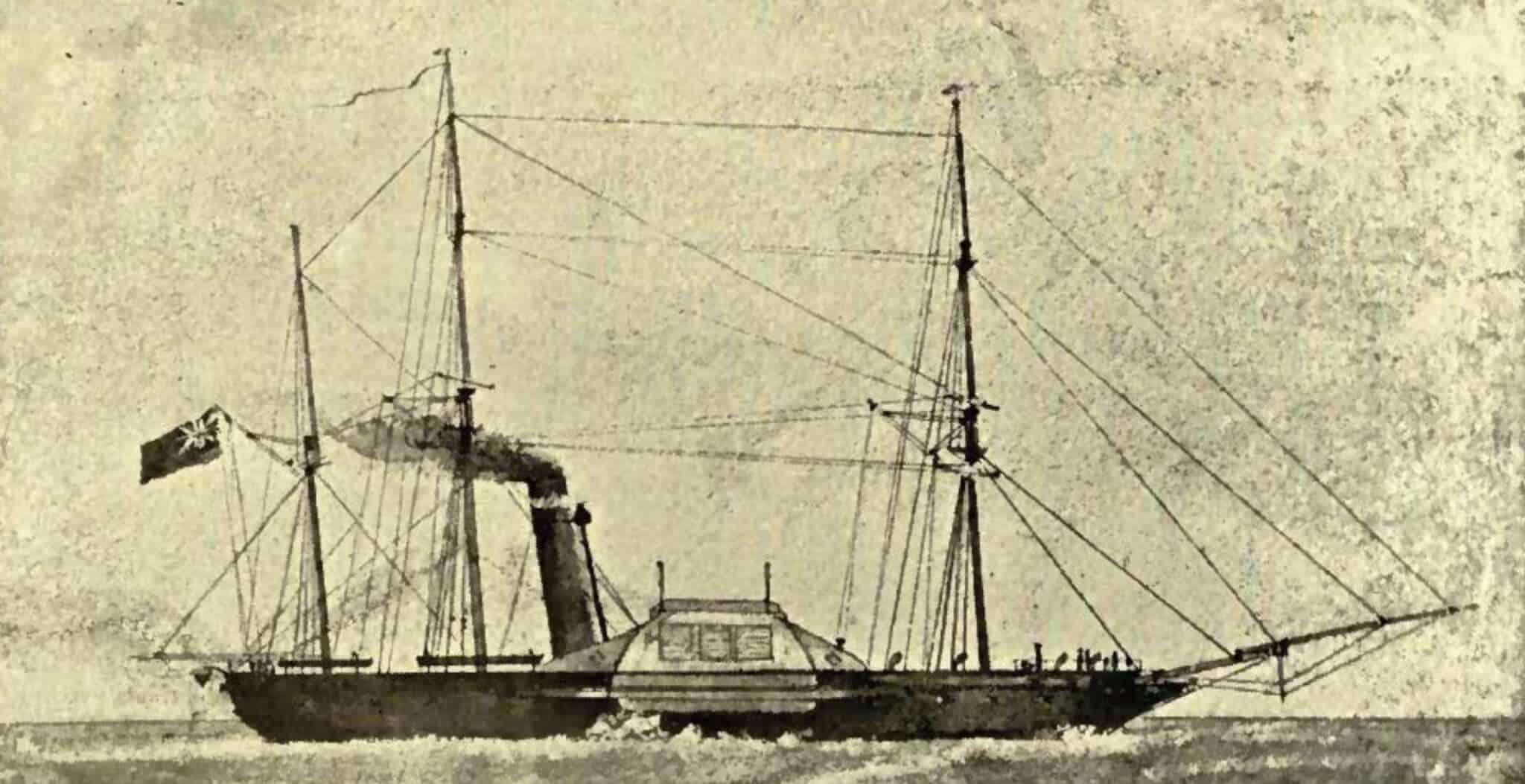

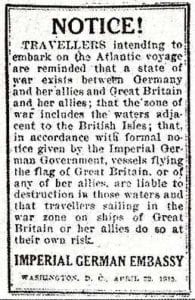

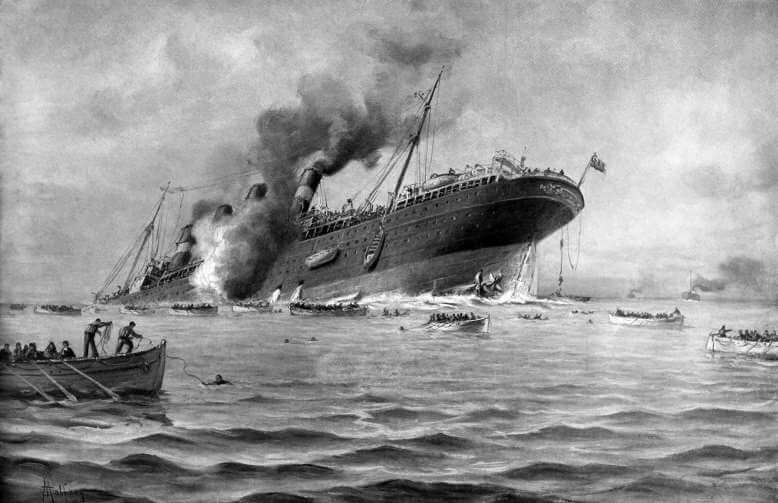

On the morning of May 1st 1915 the Lusitania left New York behind. Bound for Liverpool, few of the near two thousand passengers paid any attention to a couple of column inches in the morning newspapers carrying a message from the German Embassy. Six days later 1,195 of those on board were dead and the United States of America entered the war soon afterwards.

One survivor was the delightfully-named Maitland Kempson. Baptised 65 years earlier in the ancient church of St Kenelm’s in Romsley, Worcestershire, he was a seasoned traveller in the days before air travel became commonplace. Records from the immigration station on Ellis Island show he came here in 1911 aboard the Celtic, in 1912 as a passenger on the Baltic, in April 1915 on the Transylvania with his eventual destination each time noted as Toronto, he having family in the Canadian city. Being torpedoed did not stop his journeys, for he arrived here again in September 1916 aboard the Noordam and later made the even longer journey to New Zealand.

Clearly Maitland Kempson had access to some money and indeed was by now a wealthy man. Yet he did not make a particularly great sportsman as his four appearances for Kidderminster in 1893-94 showed. He did not take a wicket nor a catch and was not played for his batting as he amassed just fifteen runs with a top score of six. Good business decisions and the expanding industries on the West Midlands conurbation not only allowed him to see the world but also enabled him and his wife to employ at least two in domestic service. While John Asbury chauffeured the man of the house, Mrs Kempson was aided by Annie who acted as nanny to their children. John continued to drive for his employer after he married Annie, doing so until shortly before the birth of their second child in 1923. By this time Maitland had retired and no longer needed a chauffeur, hence the couple left and were presented with a trunk which had accompanied Maitland Kempson on his travels.

Our story moves forward more than forty years when the now-widowed Annie Asbury relates the story of the battered old trunk to her grandson – myself. Unfortunately, memories become twisted in the retelling and while the story of its rescue from a sinking large passenger ship are more or less correct, the name of the vessel had somehow become the Titanic. Even at my (then) tender years I realised this made no sense. Why pull a trunk from the freezing waters in mid-Atlantic when people were drowning all around? Of course, with the Lusitania the trunk washed up on the coast of Ireland as it sailed close to shore – some still maintain too close, making it a likely target for the U-boats patrolling near to land.

Another forty-plus years ahead in time and a funeral brings members of the family together. As rarely-seen relatives exchange memories, a reminder of the trunk and my maternal grandparents’ employer prompted me to try to discover what had happened to this piece of history. The timing could not have been better, for I managed to rescue a large number of irreplaceable photographs before they were consigned to the lit fire. Photographs discarded, so I was told, as these were ‘personal’ and of ‘unknown people’. Among these I later discovered two images of Maitland Kempson, both taken late in his life.

At the time, still unaware of the Lusitania’s role in this story, I decided to try to find something out about Maitland Kempson. With the advantage of modern technology and the vast store of information at our fingertips I logged on and entered the name into a search engine. Expecting little more than finding these as surnames, I was taken aback by the volume of links to sites where he is mentioned. Within moments I realised the truth. Maitland Kempson had been one of the fortunate individuals to survive the torpedoing of the ship and had even managed to retrieve a part of his luggage. My interest piqued, I examined the reasons for the attack and why it was pivotal in the role of the United States entering the war.

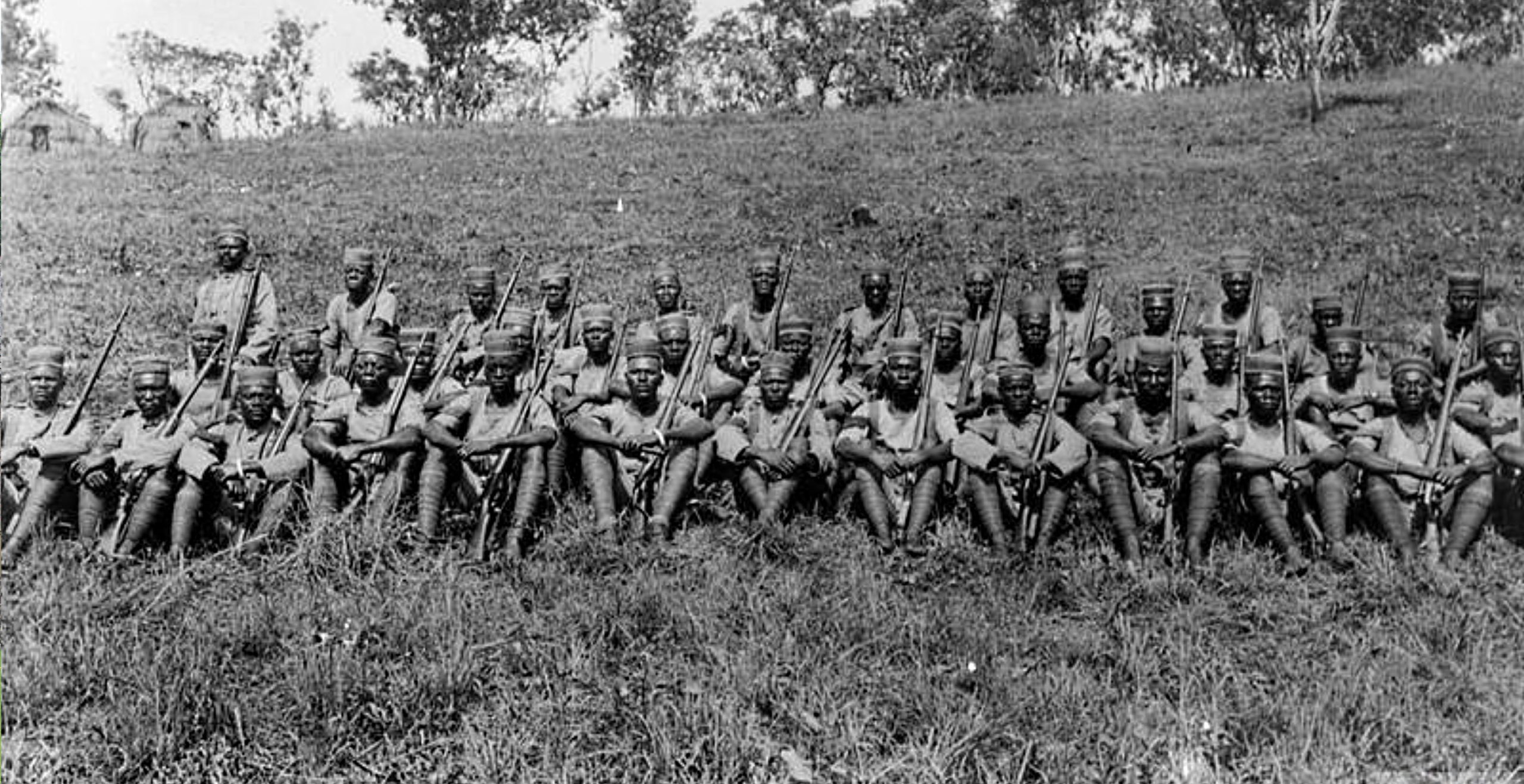

More than a hundred of the passengers who embarked on the voyage on the first day of May were Americans. While this undoubtedly contributed to the wave of outrage at an attack on an unarmed vessel – this in marked contrast to the civilised warfare of the nineteenth century – it does not explain why the vessel was attacked. Much of the blame for the ship’s fate has been levelled at her commander.

Captain William Turner steered much closer to the shoreline than recommended by the Admiralty, although not as close as his predecessor on earlier wartime crossings. He had also slowed his speed, his vessel’s best defence against attack, later stating he was concerned by the patchy fog. When asked why he did not follow the zig-zag course recommended, he maintained this applied only after sighting the submarine. Perhaps Turner followed his instincts but possibly he should have taken more notice of the three vessels sunk by German U-boats just prior to the Lusitania entering these waters.

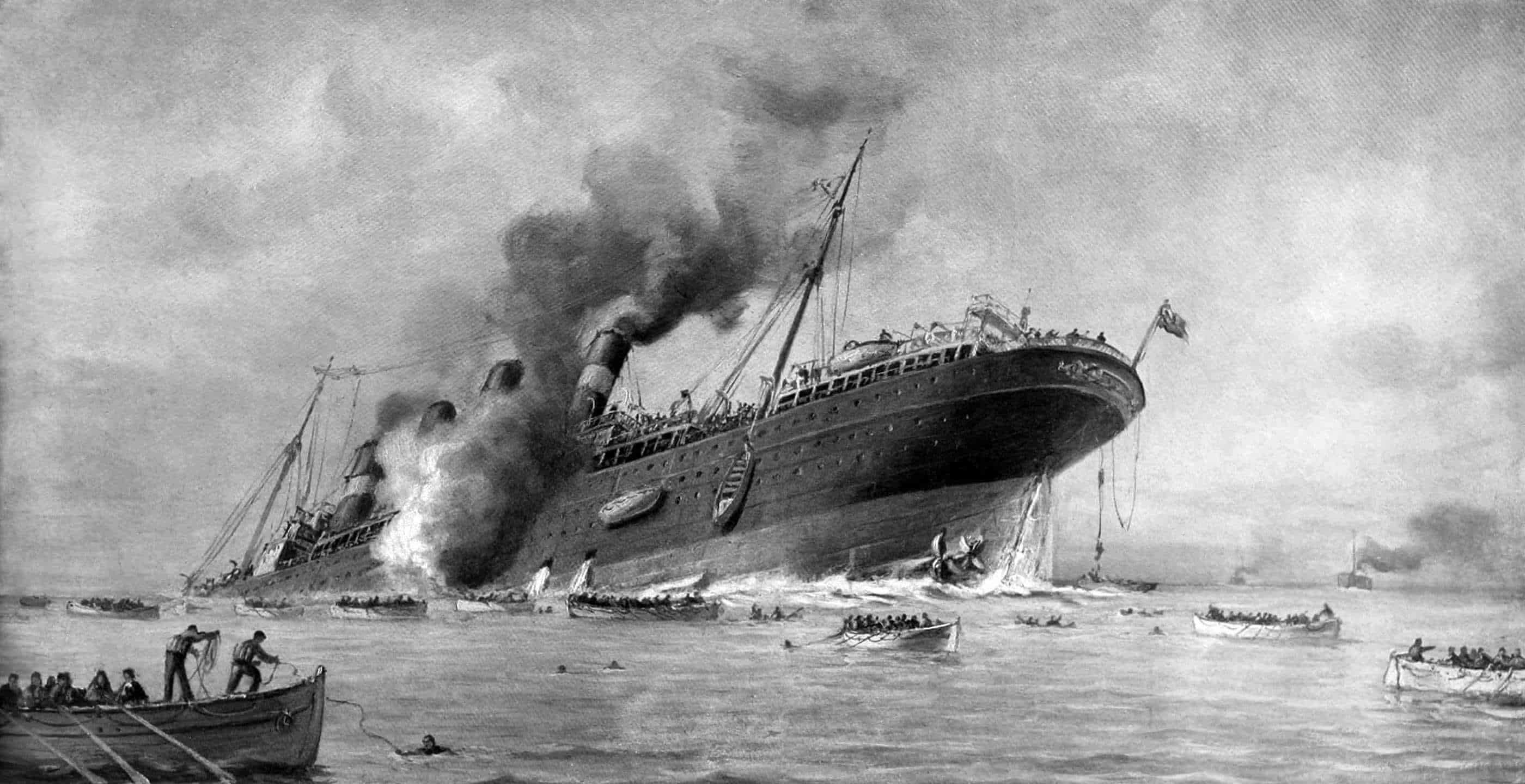

Whether Captain Turner could be held culpable or not, his actions certainly brought him within range of U-20 under Kapitanleutnant Walther Schweiger. Seeing the huge vessel in his sights he followed orders and fired upon her. The single torpedo struck just below the waterline and within eighteen minutes she had slipped below the surface to settle on the sea bed 295 feet down where much of it still lies.

Whilst the torpedo did inflict great damage it was not the reason for the sinking. That was down to the much larger secondary explosion, leading to several conspiracy theories. Most often it is said the vessel carried munitions from the supposedly ‘neutral’ US, stored in the ballast tanks. Others point to the warning in the newspapers of an impending attack, suggesting the explosives had been set by the British to bring the United States into the war. No evidence from the wreck can confirm or deny either suggestion as numerous salvage operations have destroyed any worthwhile evidence.

The Germans later released the Lusitania Medallion to mark the sinking. Initially these were dated the 5th but were subsequently withdrawn and reissued dated the 7th. Often this is cited as evidence the Lusitania had been deliberately targeted saying the Germans had prior knowledge of the munitions and knew exactly where to target, with the medallions being struck before the vessel had set sail. More likely, whether the Germans knew anything or not, these were simply produced with the wrong date. Any suggestion of the torpedo being deliberately aimed at a single point on the hull is ludicrous, early twentieth-century technology quite incapable of such.

Maitland Kempson continued to enjoy life until his death in 1938. Whether his Canadian connections represent his ancestry or if they had emigrated from England is not known. Yet ironically the child born to my grandparents shortly after leaving the Kempsons’ employ grew up to marry a Canadian and went to live there in the 1950s. Until recently she still lived in Canada, passing away peacefully soon after her 93rd birthday in January 2018.

The trunk is still missing, likely destroyed by one ignorant of its significance. Whomsoever did get rid of it probably believed it was a piece of junk saved from the Titanic making its destruction even more incredulous as relics from that vessel would be worth much more than a piece of flotsam from the Lusitania.

By Anthony Poulton-Smith. After twenty years in light engineering, I have turned to writing. Since then I have seen 75 of my own books in print, some 1,800 articles, and ghost-written over 200 other books. Many of these cover origins of place names, for etymology is my true calling and I offer many talks on a variety of themes. I am chair of Tamworth Literary Festival, member of MENSA, a trainee magistrate, also active on several other committees in my native Tamworth (Heritage Trust; Friends of Tamworth Castle; Together 4 Tamworth; Talking Newspaper for the Visually Impaired, Tame Valley Wetlands, Tamworth History Group), and recently returned to study at the Open University. Also the proud owner of a Countdown teapot.