The Great War of 1914 – 1918 was the epicentre of change for not only a whole generation and their society, but for technological advances, international relations, and importantly – modern British Intelligence.

Cited as a war of attrition, the first ‘modern war’ required a co-operative and institutionalised intelligence service if the Allies were to successfully ‘wear down’ the Central Powers with military technological capability and sufficient resources. Before The First World War and the subsequent period of rapid technological advance, British Intelligence was seen to be rather cloak and dagger and was incredibly limited in terms of size and ability. The pre-war years were filled with fear over German Imperial expansion and stories of German spies on British soil: when war was to break, Intelligence would be essential to British success.

Intelligence, in its most simple form, is really just knowledge and was available in three forms throughout The Great War: Signals Intelligence (SIGINT), Image Intelligence (IMINT) and Human Intelligence (HUMINT). SIGINT played an incredibly important and varied role throughout the war, whilst IMINT and HUMINT were somewhat unreliable and fragmentary. IMINT, usually from aerial reconnaissance, gathered geographical intelligence in the form of enemy troop locations, but its value diminished once the front lines had solidified and German troops had ‘dug in’.

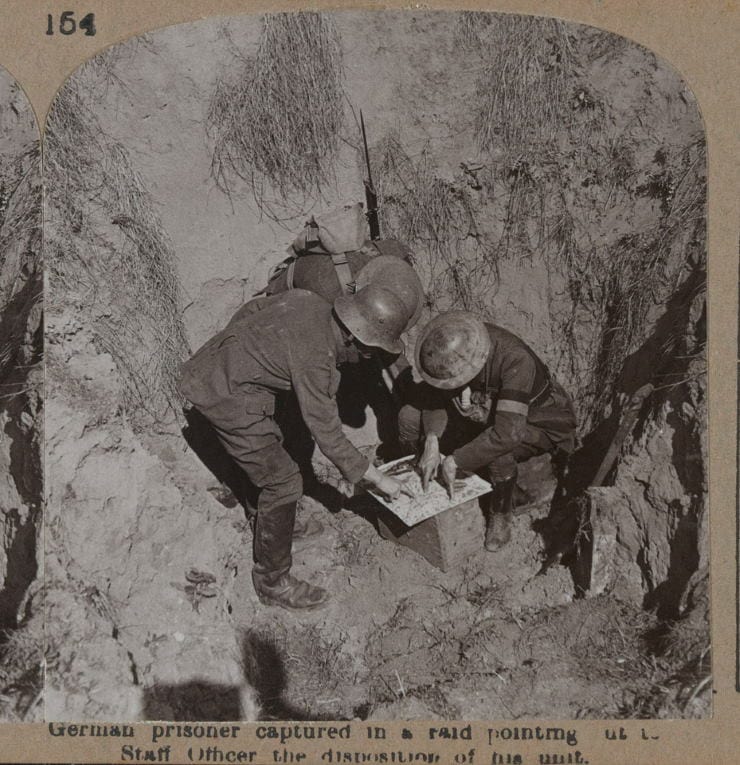

HUMINT was regarded as the most important form of intelligence, as primary source accounts are usually most reliable. HUMINT successes were often few and far between but were valuable in the cumulative insight they allowed. In May 1917, British Intelligence struck gold when a German deserter bought with him the latest version of the German Post Office directory; this listed the location of every mailing office in the German army and allowed the British to pinpoint the location of individual units. The British Army was then able to maintain an understanding of the German Army’s order-of-battle and fulfil the aim of intelligence: to minimise uncertainty about the enemy and to maximise the efficiency of the use of one’s own resources.

Another incredibly important form of HUMINT was found outside the battlefield and in the interconnected networks of La Dame Blanche – a female resistance organisation victorious in infiltrating German intelligence in Belgium and Northern France.

Female intelligence agents were so successful in gathering and relaying information on German movements thanks to their position on the home front. These women in fact displayed some of the bravest manoeuvres in The Great War. Edith Cavell was a British nurse and intelligence agent who succeeded in aiding some 200 Allied soldiers escape from German occupied Belgium: for her bravery, she paid with her life.

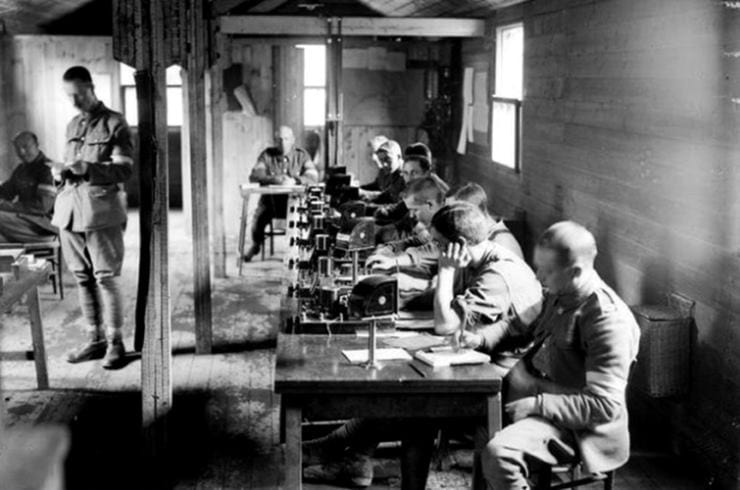

On the battlefield, SIGINT dominated intelligence gathering in order to infiltrate the enemy’s order-of-battle, the “bedrock of all intelligence.” Next to combat troops, SIGINT was the army’s most valuable resource. Whilst SIGINT provided the British Army with invaluable intelligence, it also cancelled out much of its own effect as signals failure extensively hampered all Armies in the war.

Technologies old and new were extremely unreliable and had never before been tested in such a destructive theatre of modern warfare. Artillery fire cut telephone wires making interception impossible, messengers were killed, and even carrier pigeons were shot and eaten by one’s own troops.

SIGINT, and in fact intelligence itself, is never one sided: whilst you are intercepting the enemy, he is intercepting you. The Germans had superior intelligence on the British order-of-battle throughout 1916 and successfully identified 70% of British units on the front during the Somme. Records even suggest that their intelligence also warned of the times and locations of the divisional attacks that would take place on the first day of battle.

Whilst Germany possessed intelligence services of equal skill to the Allies, their intelligence successes could not determine them as victors of war; this is because intelligence alone does not win wars. Take again the example of the Somme and the success of the German Army in the early stages of the battle. It was not superior German intelligence that encouraged their early victory but more the tactical failures of the British Army. 66% of Allied shells fired in the first bombardment on the Somme were shrapnel and could not cut the defensive steel wire of the German front line; this hindered advancement, trench infiltration, and played a definitive role in the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army.

Outside of the battlefield was where intelligence perhaps played the most important role in the war of attrition. Economic historians have emphasised that in circumstances of ‘total war’, troop numbers and supplies play the decisive role in eventual victory. Intelligence was therefore necessary to percolate into all locations, institutions, and structures of war as to defeat the enemy on the home front is to allow for defeat on the battlefield.

SIGINT was at the centre of some incredible intelligence feats during the war – most notably with the decryption of the Zimmermann telegram. In 1917, the Division of Naval Intelligence’s ‘Room 40’ successfully intercepted and decrypted a telegram containing German Foreign Minister Zimmermann’s suggestion that Mexico wage war on the United States (US) to regain lost territories. Britain fed this “propaganda weapon” to President Wilson knowing that outrage and the abandonment of neutrality would follow; six weeks later the US entered the war on the Allied side. The US bought with them over two million soldiers who landed in France in the final years of the war. Given the nature of attrition, these men were much needed resources to fight against the diminishing manpower and morale of the German army, who, since the beginning of August 1918 had lost 228,000 men – half through desertion.

It should be noted that intelligence was not the only contributing factor to the US’ decision to enter the war – first was the sinking of the Lusitania in 1915 followed by the German decision to resume unrestricted submarine warfare in January 1917. Intelligence worked the most effectively in conjunction with these events to influence US movements.

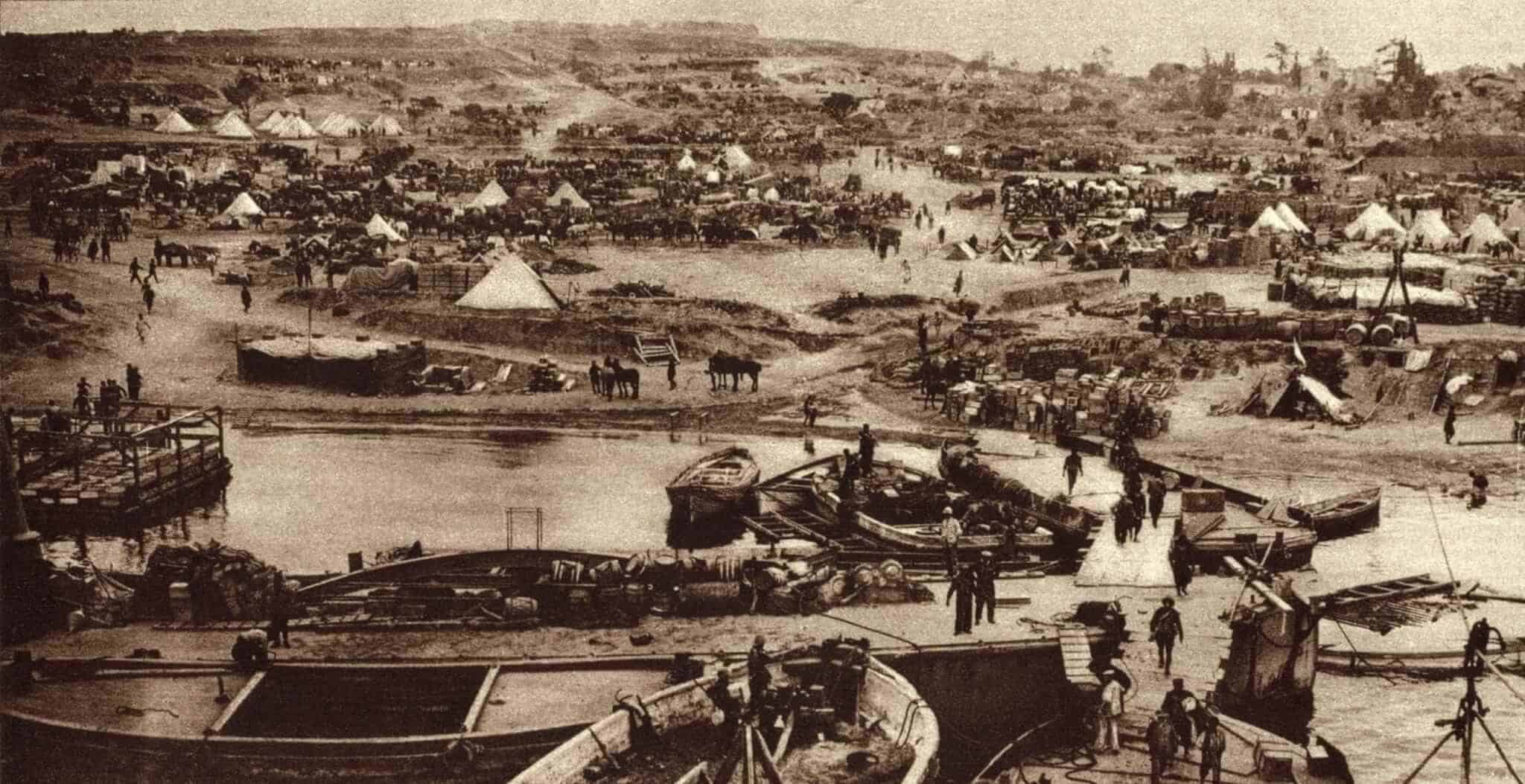

An Allied victory was not possible through battlefield victory alone; it was the devastating impact the collapse of the German economy had on their army that led the Allies to victory. Contributing significantly to this collapse was the work of British intelligence to influence the naval blockade of Germany.

Churchill, then The First Lord of the Admiralty, created the Restriction of Enemy Supplies Committee (RES) in August 1914 to monitor supplies reaching Germany by collecting intelligence from various sources. HUMINT from agents infiltrating dockyards detailed exact intelligence about the types of cargo being shipped to Germany. The German blockade was especially wide reaching, with the German army and her civilians beginning to feel its effects with diminishing munitions supplies, food and morale.

Intelligence was successfully utilised throughout the Great War and had a definitive impact on its outcome. It proved to be an irreplaceable asset when the British Army adopted it alongside strategic and tactical movements. It is true that no one event decided the outcome of the war, and intelligence certainly did not win the war alone, but it did significantly contribute to eventual Allied victory.

Olivia Jessup holds an MA in Intelligence and International Security from King’s College London. Her interests lie in the fields of counterintelligence, the history of covert operations, and the ethics of intelligence.

Published: April 7, 2021.