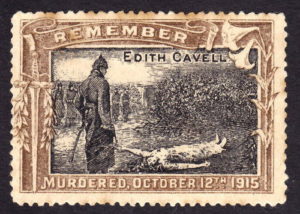

“Patriotism is not enough. I must have no hatred or bitterness towards anyone.”

These were the words spoken by Edith Cavell before she met her fate at the hands of the German firing squad. The forty-nine year old British nurse had served during the war; motivated by her strong sense of duty, she helped many soldiers without discrimination and yet would pay the ultimate price.

Her story began in December 1865 in a small village called Swardeston near the city of Norwich. The daughter of a vicar, she was the eldest of four children and had a happy childhood surrounded by nature and animals.

Her early education was at home and was followed by her attendance at the high school in Norwich before going on to study at three different boarding schools where she excelled in French.

At the age of twenty-two she began working as a governess and served in various homes, including her first in a household in Steeple Bumpstead. She then went on to serve as a governess for the Gurney family at Keswick New Hall where she left a good impression on the children.

Around this time she had come into a small windfall from an inheritance, enabling her to take a holiday to Austria and Bavaria. It was here that she witnessed the free hospital run by Dr Wolfenberg and was to be inspired by the prospect of nursing.

Before embracing her true passion for nursing and medicine, she returned to work once more as a governess, this time for the Francois family in Brussels where she became a well-liked member of the family and served them for five years.

She would spend her summers returning to her home in Swardeston where she engaged in a brief romantic liaison with her second cousin Eddie.

In 1895, her time with the Francois family was cut short when she heard news of her father’s ill health, forcing her to return to England to personally take care of him and nurse him back to health.

This experience would inspire her change in career as she realised that nursing was something that she felt strongly about and therefore, at the age of thirty she applied to become a nurse probationer in London.

This would become the first of many nursing roles she took on, including in several London hospitals before she worked as a travelling nurse visiting her patients in their homes.

As such, this varied work would give her a great amount of experience and skill as she had come into contact with various ailments that would hold her in good stead for her later work during the First World War.

In the meantime, she applied herself wherever and whenever she was needed, including in 1897 when she was called on to assist in suppressing a typhoid outbreak in Maidstone, in the southeast of England. For her work, like her peers, she was awarded the Maidstone Medal in recognition for her contribution.

In 1906 she moved up to Manchester and worked for a few months in a temporary role as a matron.

A year later, a new nursing school opened in Belgium called the Berkendael Medical Institute. Under the leadership of Doctor Antoine Depage, a famous Belgian royal surgeon and the founder of the Belgian Red Cross, Edith Cavell was called upon to offer her expertise.

She subsequently accepted the position and in the years that followed would play an instrumental role in establishing modern methods of nursing in the Belgium school whilst also publishing a nursing journal called L’infirmière”.

During her time in Belgium she fulfilled a valuable role as a teacher to many student nurses, supplying medical professionals for three hospitals, twenty-four schools and around a dozen kindergartens.

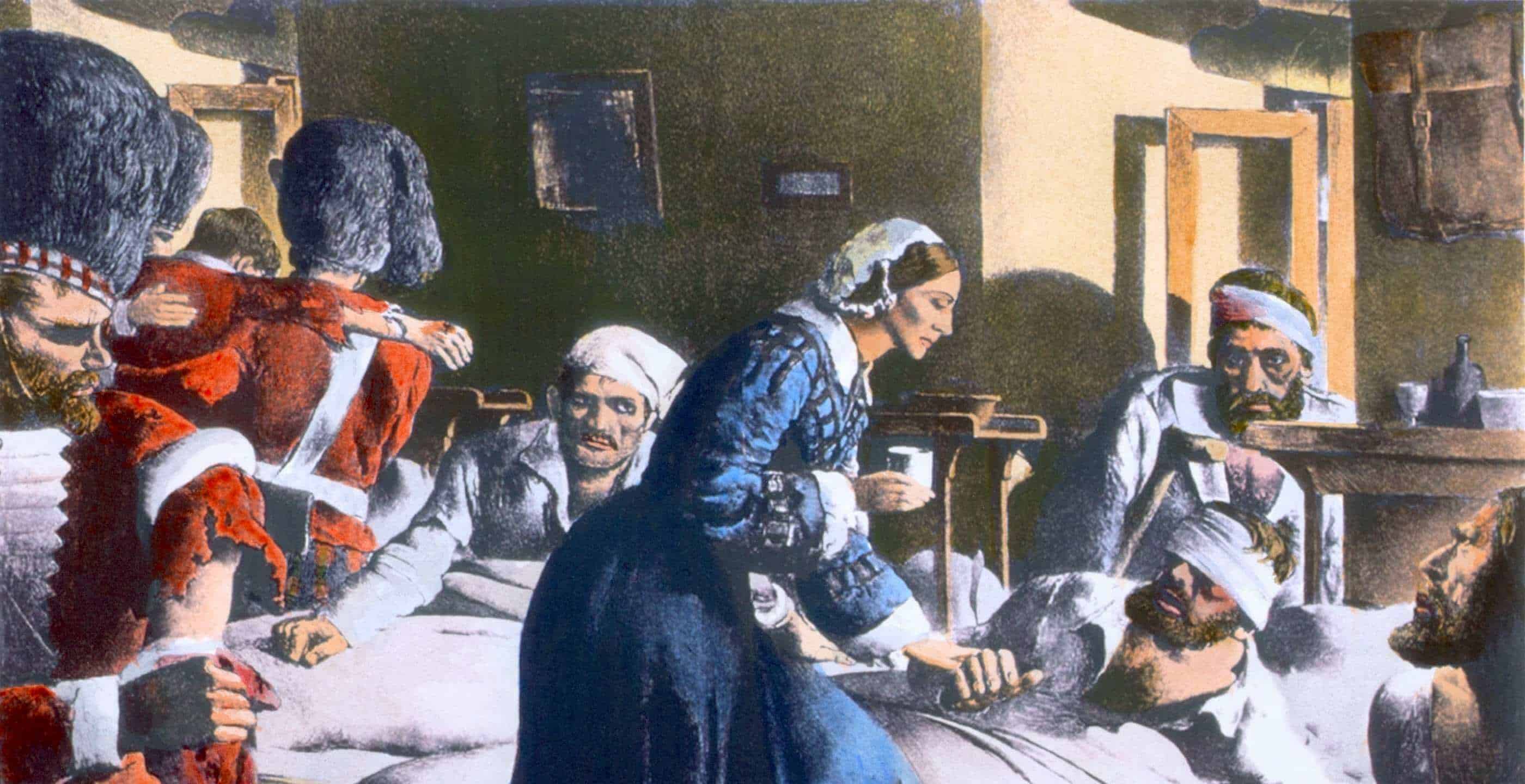

Cavell would work side by side with Depage who recognised her potential and the skills she was offering his students. Depage and others like him recognised the need to make more headway with modern medical treatments, inspired by the work of Florence Nightingale.

Until now, the medical response had been dominated by religious institutions who despite being well-intentioned lacked the necessary skills to make the advancements that were necessary for pioneering new treatments and saving more lives.

Now more than ever, medical advances were required to treat a wide range of ailments and diseases which continued to ravage populations across Europe.

In 1910, Cavell was offered the position of matron at the hospital at Saint-Gilles.

Four years later the outbreak of the First World War would make the work of Edith Cavell and others like her more important than ever.

In the year that war was declared, Edith had managed to juggle a full schedule of nursing work, teaching, including giving four lectures a week, as well as looking after her two dogs, Don and Jack.

After a brief trip to visit her mother, Edith Cavell learned the news that sent shockwaves through Europe. The declaration of World War One changed everything and Edith knew more than most how necessary her work would become and so she left her mother back in Norfolk and returned to Belgium.

As soon as she arrived, Edith made it clear to all the other nurses under her care that their duty would be to take care of the wounded regardless of their nationality: as a Red Cross Hospital, both sides were to be treated equally.

As the Germans made their advance, Brussels fell and was taken over, including the Royal Palace which had been repurposed for the wounded German soldiers.

Whilst sixty nurses from England returned home, Edith Cavell alongside her assistant, Miss Wilkins remained in Belgium.

In the meantime, two British soldiers had managed to find their way to the nursing school and were sheltered by Cavell for two weeks. This would not be the first scenario of this kind to play out, as others walked through her doors and were given safe passage to the neutral Netherlands.

For almost a year, an underground network developed whereby 200 allied soldiers were able to find shelter and eventually escape, thanks to Nurse Cavell and all those involved included Prince and Princess de Croy who had devised the scheme.

With such a daring plan came a great amount of danger as all those involved knew the risks if they were found to be hiding Allied soldiers.

For Edith, her involvement in the network became inextricably linked to her sense of duty, both as a nurse and humanitarian. Whilst her protected status as a member of the Red Cross demanded her neutrality, the war had required more risk and sacrifices from Edith who felt compelled to help as many people as she could.

The following year a Belgian collaborator was pursued by German soldiers to the nursing school. Whilst the building was searched, the escapee managed to elude the soldiers and find a way out without being seen.

Meanwhile, Cavell had gone to great lengths not to involve the other nurses for fear that they may be caught up in these clandestine affairs.

Sadly, the team’s luck ran out and in July 1915, two of those involved in the underground network were arrested.

Only five days later, Edith Cavell was arrested on the suspicion of harbouring Allied soldiers. It would later be revealed that Georges Gaston Quien, a collaborator, had betrayed her to the German authorities.

After being held for ten weeks at the prison in Saint-Gilles and interrogated by the German police, she admitted her involvement in the sheltering and smuggling of British, French and Belgian soldiers and civilians.

With the Germans having acquired a confession out of Edith Cavell, she was prosecuted for aiding Allied soldiers and accused of treason.

One day before her trial she signed a statement confirming her guilt as the reality of her situation became increasingly stark; she was subsequently sentenced to death.

News of her sentencing immediately provoked outrage in the international community as efforts were made by various governments to have her sentence commuted. These attempts, including from the neutral governments of Spain and the United States sadly proved unsuccessful.

Whilst her status as medical personnel technically gave her protection under the First Geneva Convention, sadly this did not extend to medical professionals who engaged in belligerent action, therefore forfeiting their rights to protection.

This left the British government with very little scope for providing assistance to Edith Cavell. As such Robert Cecil who was Under-Secretary for Foreign Affairs at the time was said to have claimed that any representation by the British government would have “done more harm than good”.

Despite this, the United States continued to exert pressure on Germany but to no avail. Edith Cavell’s fate was sealed.

The night before her execution Cavell, now resigned to her fate, confided in the chaplain Reverend Horace Graham, revealing that she had made peace with her actions and did not have hold any resentment.

The following day, on the morning of 12th October 1915, Edith Cavell was shot by a German firing squad.

The news of her death sent shockwaves around the world, stirring anti-German sentiments as well as uniting others in both pride and grief.

Edith Cavell first and foremost was a nurse, someone with a duty of care who felt compelled to help as many people as she could at a time when so many lives were being lost. Such a sentiment would cost Edith her own life and with that, left a great legacy amongst not only those she had saved, either through treatment or sheltering, but the international community who respected her actions and recognised her for her martyrdom.

Jessica Brain is a freelance writer specialising in history. Based in Kent and a lover of all things historical.

Published: 10th November 2021.