July 1st 1916 – the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army; The Battle of the Somme

On 1st July 1916 at around 7.30 in the morning, whistles were blown to signal the start of what would be the bloodiest day in the history of the British Army. ‘Pals’ from towns and cities across Britain and Ireland, who had volunteered together only months earlier, would rise from their trenches and walk slowly towards the German front-line entrenched along a 15-mile stretch of northern France. By the end of the day, 20,000 British, Canadian and Irish men and boys would never again see home, and a further 40,000 would lie maimed and injured.

But why was this battle of World War I fought in the first place? For months the French had been taking severe losses at Verdun to the east of Paris, and so Allied High Command decided to divert German attention by attacking them further north at the Somme. Allied Command had issued two very clear objectives; the first was to relieve pressure on the French Army at Verdun by launching a combined British and French offensive, and the second objective was to inflict as heavy losses as possible on the German armies.

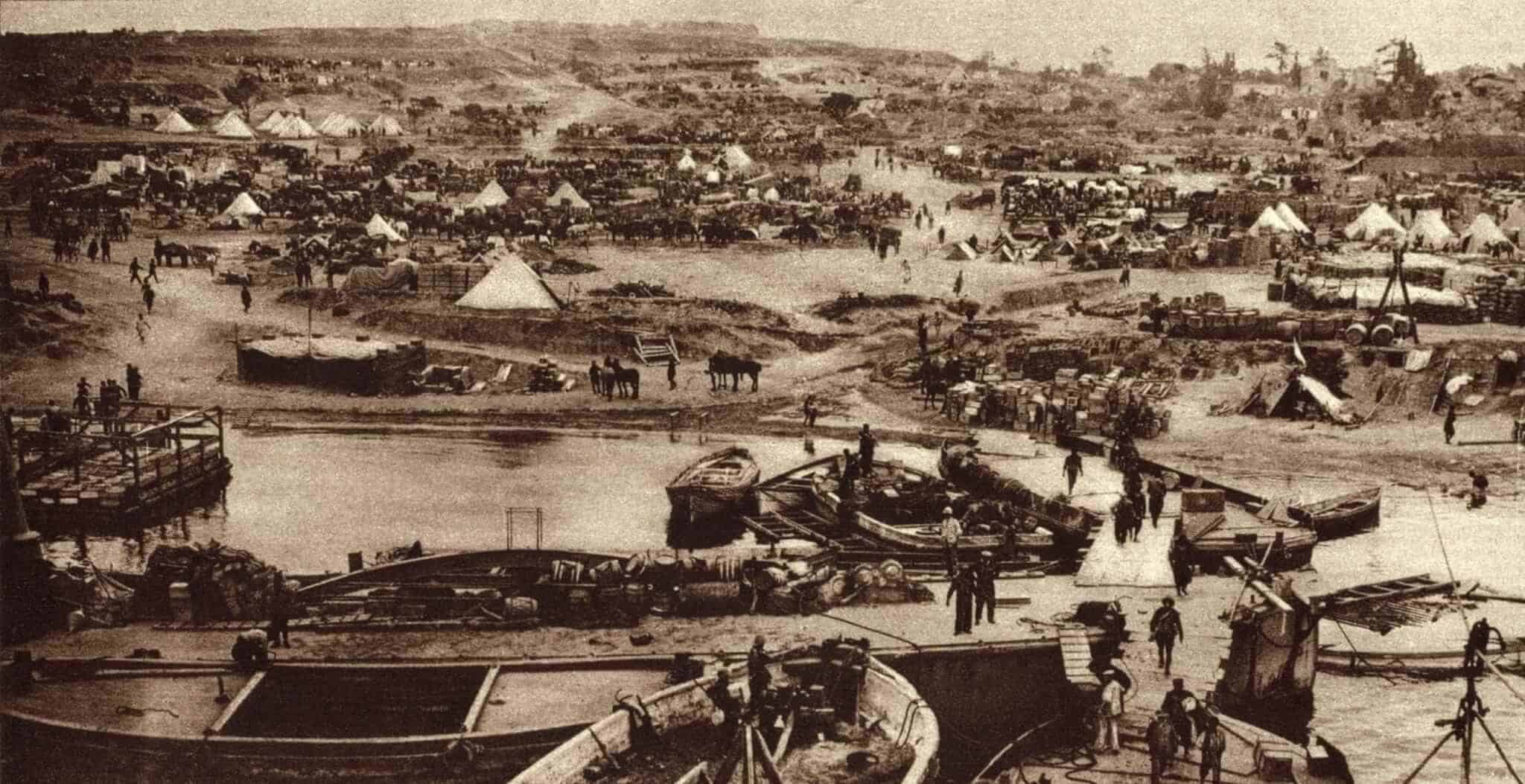

The battle plan involved the British attacking on a 15 mile front to north of the Somme with five French divisions attacking along an 8 mile front to the south of the Somme. Despite having fought trench warfare for almost two years, the British Generals were so confident of success that they had even ordered a regiment of cavalry to be put on standby, to exploit the hole that would be created by a devastating infantry attack. The naïve and outdated strategy was that the cavalry units would run down the fleeing Germans.

The battle started with a weeklong artillery bombardment of the German lines, with a total of more than 1.7 million shells being fired. It was anticipated that such a pounding would destroy the Germans in their trenches and rip through the barbed wire that had been placed in front.

The Allied plan however, did not take into account that the Germans had sunk deep bomb proof shelters or bunkers in which to take refuge, so when the bombardment started, the German soldiers simply moved underground and waited. When the bombardment stopped the Germans, recognising that this would signal an infantry advance, climbed up from the safety of their bunkers and manned their machine guns to face the oncoming British and French.

To maintain discipline the British divisions had been ordered to walk slowly towards the German lines, this allowed the Germans ample time to reach their defensive positions. And as they took their positions, so the German machine gunners started their deadly sweep, and the slaughter began. A few units did manage to reach the German trenches, not however in sufficient numbers, and they were quickly driven back.

To maintain discipline the British divisions had been ordered to walk slowly towards the German lines, this allowed the Germans ample time to reach their defensive positions. And as they took their positions, so the German machine gunners started their deadly sweep, and the slaughter began. A few units did manage to reach the German trenches, not however in sufficient numbers, and they were quickly driven back.

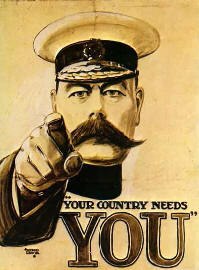

This was the first taste of battle for Britain’s new volunteer armies, who had been persuaded to join-up by patriotic posters showing Lord Kitchener himself summoning the men to arms. Many ‘Pals’ Battalions went over the top that day; these battalions had been formed by men from the same town who had volunteered to serve together. They suffered catastrophic losses, whole units were annihilated; for weeks afterwards, local newspapers would be filled with lists of the dead and wounded.

Reports from the morning of 2nd July included the acknowledgment that “…the British attack had been brutally repulsed”, other reports gave snapshots of the carnage “…hundreds of dead were strung out like wreckage washed up to a high water-mark”, “…like fish caught in the net”, “…Some looked as if they were praying; they had died on their knees and the wire had prevented their fall”.

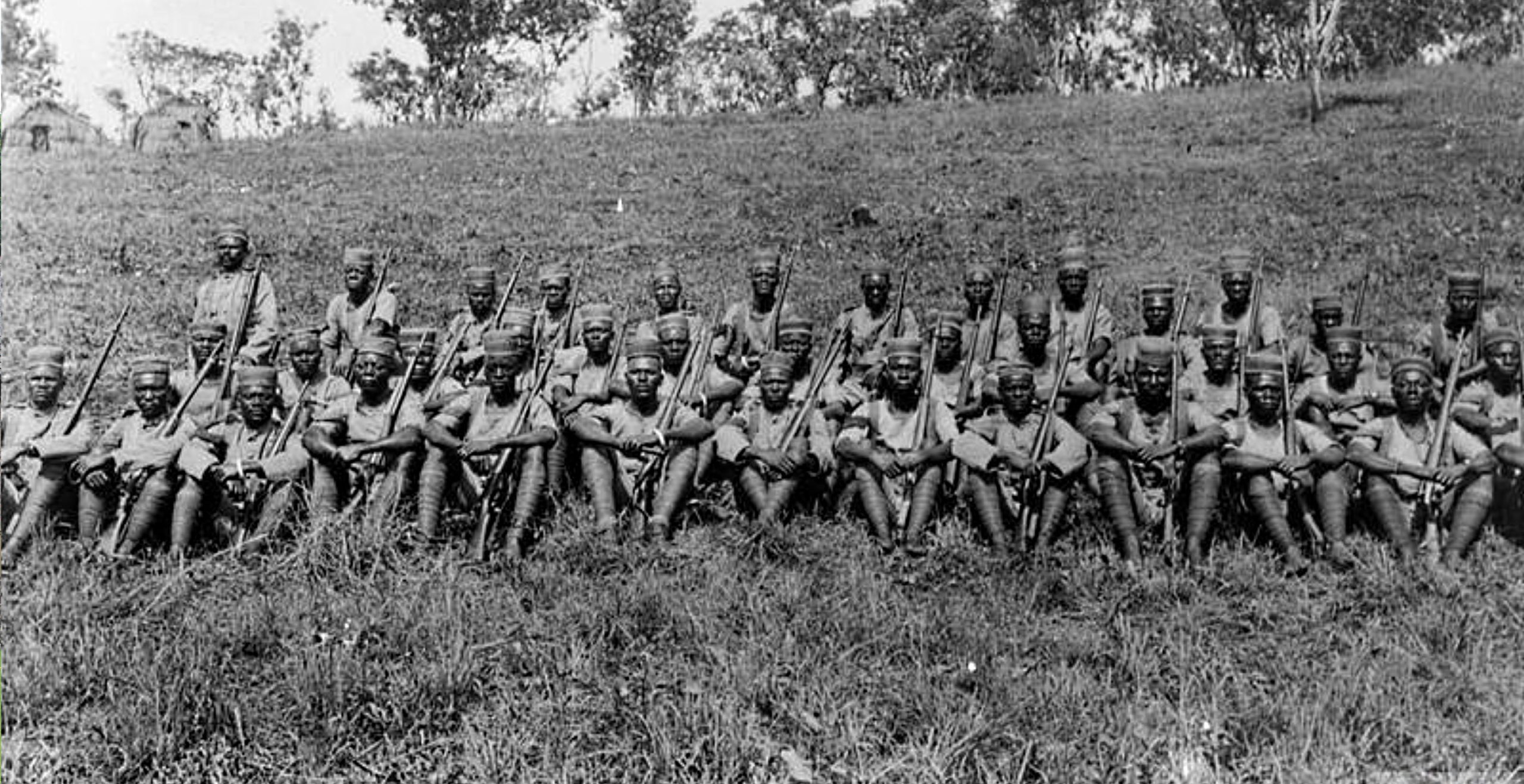

The British Army had suffered 60,000 casualties, with almost 20,000 dead: their largest single loss in one day. The killing was indiscriminate of race, religion and class with more than half of the officers involved losing their lives. The Royal Newfoundland Regiment of the Canadian Army was all but wiped out… out of the 680 men who went forward on that fateful day, only 68 were available for roll call the following day.

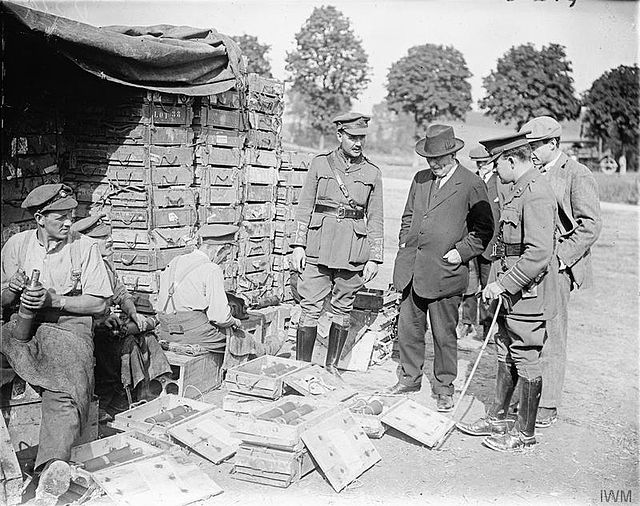

Without the decisive breakthrough, the months that followed turned into a bloody stalemate. A renewed offensive in September, using tanks for the first time, also failed to make a significant impact.

Heavy rains throughout October turned the battlegrounds into mud baths. The battle finally ended in mid-November, with the Allies having advanced a grand total of five miles. The British suffered around 360,000 casualties, with a further 64,000 in troops from across the Empire, the French nearly 200,000 and the Germans around 550,000.

For many, the Battle of the Somme was the battle that symbolised the true horrors of warfare and demonstrated the futility of trench warfare. For years after those who led the campaign received criticism for the way the battle was fought and the appalling casualty figures incurred – in particular the British commander-in-chief General Douglas Haig was said to have treated soldiers’ lives with disdain. Many people found it difficult to justify the 125,000 Allied men lost for every one mile gained in the advance.

Published: 30th June 2021.