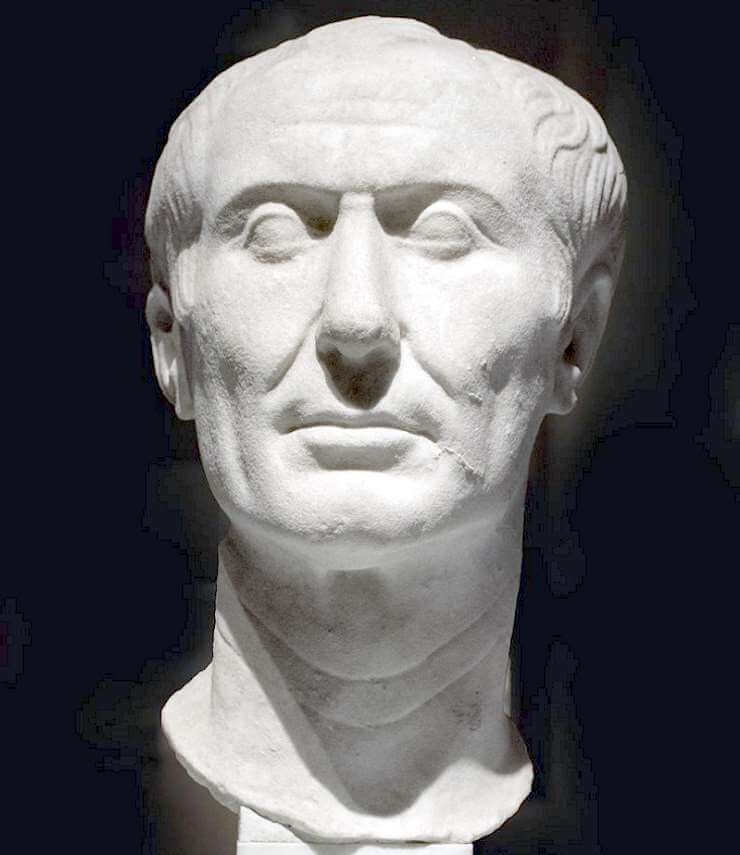

A vast amount has been written about the Roman Empire and its most popular Emperor, Julius Caesar, but very little was recorded about his two invasions of Britain. The only surviving texts from this truly ancient era are the records from Caesar himself, which were written later in Gaul and with the benefit of consideration and hindsight. In ‘De Bello Gallico’ (his account of the Gallic Wars), Caesar states that he was forced to flee Prittan and leave a great deal of booty and many slaves on the beach, due to a ‘threatening and impending storm’.

Caesar’s trite explanation of the failure of that first invasion is biased and deeply suspicious in this writer’s humble opinion, so I set out to study this mystical period in our history and some of the ancient tales associated with the Roman wars. I discovered that in later Welsh manuscripts, the age-old oral tradition of this period had been written down by the old Bards and recorded for posterity. Whether fact or fiction, these ancient Welsh texts paint a very different and vivid picture of Caesar’s invasions and I found the narrative completely fascinating. So much so, I decided to research the events properly.

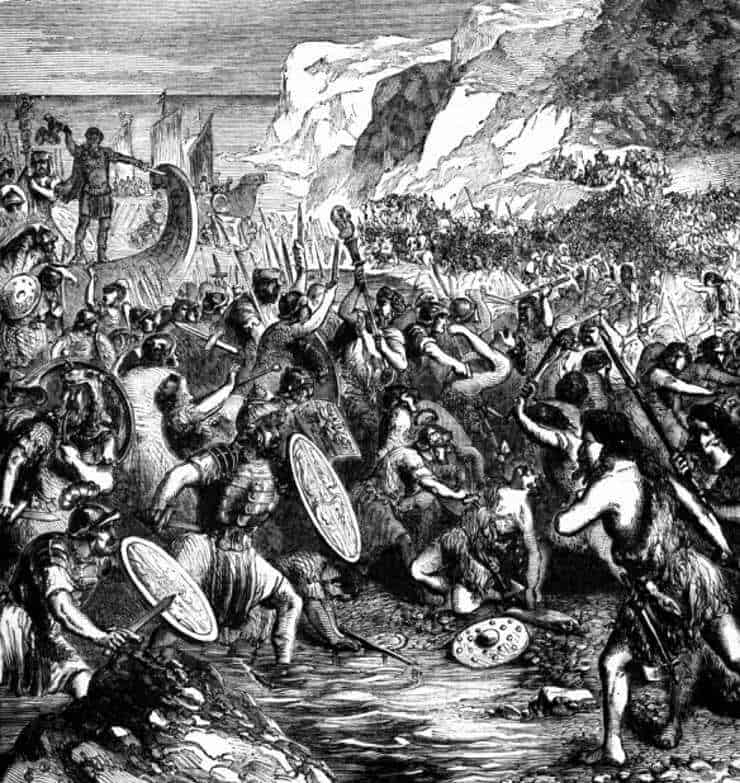

According to those later Welsh manuscripts, the allies’ first major contact with Caesar following his first landing in 55 BC was made on a flat plain of land near a stronghold known as CaerCant, (Canterbury Fort, Kent suggested). The old Bards proposed that during this battle, King Nynniaw (the 1st Nennius) and the sword-champion of all Britain was able to bring Caesar to single-combat.

In this bout of mortal-combat, Nynniaw was struck a terrible blow to the head by Caesar himself, whose sword stuck fast to his shield-rim. Nynniaw then threw down his own sword and claimed the Roman gladius from his split shield. Caesar fled at this shocking loss, as the famous son of Beli Mawr, although wounded but now armed with a Roman Gladius, slaughtered many Romans with Caesar’s own blade. However the bold and ever-ambitious Roman General managed to escape to his beachhead and flee to Gaul with the remains of his fleet. Rumours were rife at the time that ‘Caesar the Treacherous’ had poisoned his blade, as all who had been injured by it on the field of battle subsequently died, as did Nynniaw himself 15 days later in fevered agony. Caesar’s suspected poisoned gladius was labelled ‘Crocea Mors’ by the Brythons (Britons) at the time, meaning yellow or ruddy-death and eternally cursed.

It seems that Caesar only just escaped with his life on that first incursion in 55 BC, and regardless of his later personal reports written in comfort and with the benefit of justifying hindsight, it appears he was given a thorough trouncing on the hills, fields and beaches of Kent by the allied Brythons. Led by the infamous sons of the late High-King Beli Mawr himself (Lludd Llaw Ereint, Nynniaw and Caswallawn), the Brythons unite for the first time in history to repel the Roman invasion.

Caesar’s more successful second invasion was far better documented by both sides. Some historians doubted that an elephant was brought to Britain for Caesar’s second invasion, many thinking the story was confused with the Roman invasion proper of 43 AD. For Caesar’s subsequent foray in 54 BC, Caswallawn (Cassivellaunus) in his infinite wisdom and hubris decided he didn’t need the Northern Triad to help him, even though they were declared eager and ready to make the long journey south again in defence of Britain. This ‘Northern Exclusion’ was a massive insult to the northern tribes after all they had done in the first invasion and must have caused uproar and eternal resentment toward the southern tribes. It may have even been the ancient inspiration for Britain’s current north-south divide, which is still apparent to this day!

In spite of Caswallawn’s preparatory fortifications to many parts of coastal Kent and regardless of his courage and leadership, the shambles of this second defence and the internecine and treacherous, shameful back-stabbing which prevailed, remains a sad and pivotal point in the development of ancient Prydein (modern Welsh name for Britain). In this writer’s humble opinion, it marked the ending of the natural development of the ancient Celtic/Brythonic culture in mainland Britain, eventually changing the form and manner of Britons themselves. Regardless of the southern tribes’ supplications to Rome, Celtic Britain had almost a century to organise itself prior to the true Roman invasion of 43 AD, but they spent this time mostly adopting the culture, dress and attitudes of Rome, fighting each other and manoeuvring for more personal power, land and wealth.

Sadly or happily depending on your viewpoint, a cynical, technological age had come to replace a mythical, magical era and nothing in Britain would ever be the same again but hey, at least the roads got sorted out!

By Eifion Wyn Williams. I am a 60-year-old Welshman raised in North Wales by a family of historians, poets and teachers. My father was one of 11 children brought-up in Porthmadoc in Snowdonia and became the Headmaster of my infant and junior school. This was Llanllechid Primary School, situated in the cold foothills of Eryri and above the small town of Bethesda. With such a large and knowledgeable family, I received a proper Welsh education and was imbued from infancy with a deep and abiding passion for our ancient and glorious history.

I have been writing creatively for over forty years and these ancient, largely untold stories passed down to me by my father and my grandfather, have long captured and held my imagination. I hope the ‘Iron Blood & Sacrifice’ trilogy does the history of that mystical period justice and that in some small way of my own, I have honoured our unforgettable and glorious ancestors.