Britain’s ports and harbours were once menaced by the dreaded press-gangs.

Impressment, to give it its proper name, was the scourge of maritime communities across the British Isles and Britain’s North American colonies for 150 years from 1664–1830 and involved bands of thugs headed by naval officers being sent ashore from Royal Navy (RN) warships to kidnap the King’s subjects to serve on the high seas.

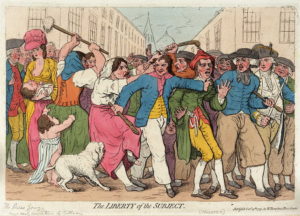

The popular image of press-gangs is of an underhand recruiting sergeant in a dockside tavern plying patrons with drink then surreptitiously slipping a ‘King’s Shilling’ into their tankard as payment for their ‘volunteering’ into the Navy, before carrying off the hapless, possibly legless fellow to a life of squalid brutality onboard a RN warship.

Tankards were made with glass bottoms because of this subterfuge so that the drinker could see if a coin was in there before he ‘accepted payment’ in drinking its contents. This is a misconception, however.

Although the Navy did prefer volunteers (by any means) rather than pressed men during the more placid interludes of empire building, the rate the Navy hemorrhaged manpower meant press gangs could take almost any man they thought suitable, and their victim was more likely to get a whack over the head with a club than a shilling.

By the 18th and 19th centuries, laws were enacted to limit impressment to seafaring professions, and in theory apprentices and foreigners were exempt. In times of national emergency or if the press gang was unscrupulous (they received bounties for every pressed man) these parameters were often overlooked. Impressment was 100% legal.

There was nothing a man could do to avoid impressment, save run… or fight.

Background

The RN suffered from a perennial problem from the years it became a major European player in the 16th century until the mid 19th century; life in the navy was a horrid and brutal one and compared badly to the pay and conditions in Britain’s merchant fleets.

And its adversaries were many.

In the 1700s for example there were no less than seven major wars the Navy had to mobilize for, culminating in Great Britain’s climactic showdown with Napoleon’s naval forces at the Battle of Trafalgar in 1805, when the RN had about 115,000 personnel. The solution was impressment, a practice started as far back as the 13th Century and was encouraged in Elizabethan times as a way to clear the streets of ever-rising numbers of unemployed. It only ended after Napoleon’s fall in 1815 when as much as 75% of the Navy were impressed men.

Some context: unlike Napoleon’s massive Grande Armee which employed widespread conscription, provoking discord nationwide as a result, British people were spared conscription, and were left largely free to enjoy their God-given liberties because a large navy requires a lot less manpower than a large army. The trade-off for Britons was impressment; a system of forced military service much more selective than conscription, but for those eligible for military service recruitment was a much more traumatic and chaotic experience; men were stolen away without warning or time to settle affairs at home beforehand. Men in seafaring trades faced the terrifying prospect that at almost any moment a press gang could turn up and seize them, beat them if they resisted, and then drag them away to a life in the navy that they may only return from if they were lucky.

All family and friends could do was cry and curse in their wake as a father, husband or son was taken away, for the press gang cared little for the suffering their actions heaped on households who were about to lose the main bread-earner, leaving them destitute in the process.

Most impressed men were actually taken from merchant ships just before they returned from long voyage, looking forward to seeing their families again only to be taken away to spend several more years away from home. The trauma this must have imposed on the men and their families can only be imagined.

Press Gangs at Work

One tale from Wales in 1803 provides a neat microcosm of the types of men subject to the press gang’s work ashore:

Six defendants appeared in court one day charged with assaulting the officer of a press gang who was carrying out his duty. Two were identified as mariners, another two were farm labourers who’d never been to sea but one had been friends with one of the mariners. There was an additional mariner who’d just returned home from a two-year voyage to the Caribbean. The last defendant had been dragged from his home leaving a wife and two small children. All six were convicted and handed over to the press gang to join the fleet. Another defendant was charged and convicted of stealing a brass pan from a field. He was also sentenced to be sent to sea.

Many impressed sailors were vagabonds or miscreants however many more were decent working men, as this press report recorded:

“On Sunday evening a press gang, attended by some of the Bow Street officers, visited the Adam and Eve public house, near Islington, when finding a large concourse of people tippling [drinking] in the gardens, and some apartments in the house, they made bold to take away such as were unable to give a proper account of themselves. The clamour and resistance of some of those who were taken, drew together a number of spectators, some of whom were removed for their curiosity, being also taken by the press gang.”

And there was no limit to the audacity of these press gangs:

“A letter from Margate says ‘Last night a naval officer landed on the pier about ten o’clock with a press gang, and having exercised his authority in a manner deemed improper by the high constable and another peace officer of this port, they interfered and informed the naval officer that the persons he had impressed were not objects of the impress act. In consequence of this interference, the gang seized the two constables, and sent them with several others on board the ship.’”

Most presumably accepted their fates, but not everyone. Some tried to flee in desperation:

“Friday morning a press gang having information that several sailors were secreted in a house in Orchard Street, Westminster, entered it, and one man, in endeavouring to escape from the top of the house, fell into the yard upon the top of a pump, and was killed on the spot.”

A story of one man’s desperate escape in a fishing village in 18th Century Ireland:

“A press gang crashed into the ‘McAlpin’s Suir Inn’ and a young fellow ran out the door, fled into a neighbour’s house, jumped through a window and landed in the lap of the house owner’s daughter. She started to scream and he gagged her and the house owner came in and said ‘it’s either the press gang or my daughter’. So, he chose the daughter. But for years afterwards when he’d get drunk in McAlpin’s at the bar, he’d mumble into his pint ‘I should’ve went with the press gang.’”

Fighting Back

As the ideas of liberty in the Age of Enlightenment took hold, there was an ever fiercer conflict between one’s concept of duty and individual sovereignty, illustrated by an anecdote by the famous French philosopher Voltaire who told of the time he found a Thames waterman, who had been boasting about the liberty of Englishmen, confined the next day in a prison cell by the press gang.

Reports swelled of sailors and townsfolk banding together to fight off these despised gangs of marauding thugs, and often quite successfully. Yet more reports from ‘The Times’ newspaper from 1790 show what happened when press gangs were thwarted in their efforts:

“Friday night, about 10 o’clock, a press gang made their appearance in Oxford market — As they were carrying off a butcher’s lad, they were beset by a large party of the sons of the cleaver, and received so complete a drubbing [beating], that they were glad to relinquish their prisoner, and shelter themselves in a beer-house in Berwick-Street, the Lieutenant narrowly escaping with his life.”

“Monday, as four sailors, who had returned from sea a few days before, were drinking in a public-house in Atherton Street, Liverpool, they were attacked by a press gang, but the sailors having fire-arms with them, warned the gang to keep off; This they did not attend to, and were coming to seize the sailors, when they fired, and one of the press gang was killed upon the spot, and another very dangerously wounded.”

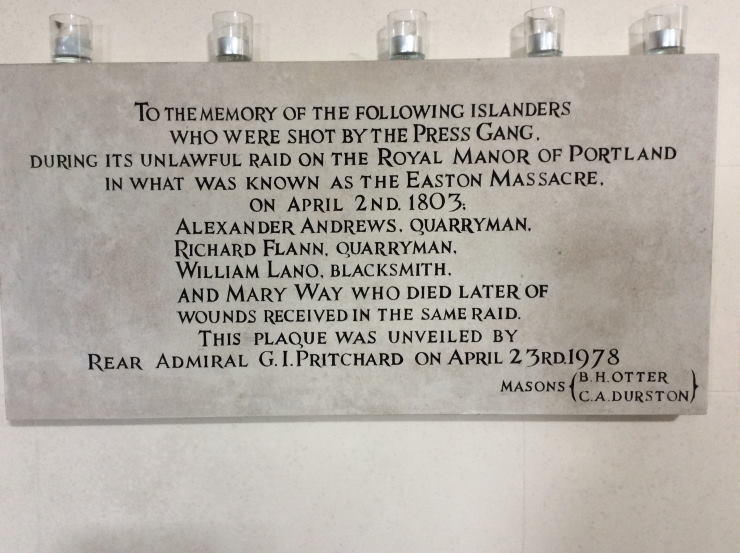

Of course, some attempts to resist the press gangs went badly for the civilians such as the Euston Massacre of 1803. There, a band of Marines landed on Portland Isle in southern England in the small hours of the morning to catch the locals whilst they slept. (even though all men on the isle were actually exempt from impressment.) Two men were quickly apprehended and a large crowd gathered to try to block the naval party and protest, but were fired upon. Three men and a woman died from their wounds. The pres -gang returned to their warship empty-handed, at least.

An End to Impressment

As Britain evolved from a medieval society to a modern, enlightened one in the 18th Century it found it ever harder to reconcile the callous brutality of impressment with Britain’s ever-strengthening notions of liberty and individual sovereignty that are the cornerstones of Western conscience.

Britannia’s mastery over the seven seas after 1830, a skyrocketing population, plus greatly alleviated conditions of employment in the RN put an end to impressment for good.

Today, stories of press gangs still provoke an emotional reaction.

Al Lee lives in Cardiff and loves nothing more than to unearth and write about the obscure yet intriguing tales from History. He also teaches English as a 2nd Language.

Published: 22nd August 2021